This is a guest post by Maximilian Mosher.

I’m sorry to disappoint you but Bert and Ernie are not gay. They’re not. When Jim Henson and Frank Oz created them for Sesame Street they were intended as a tribute to the grand tradition of mix-matched comic duos—Laurel and Hardy, Abbot and Costello, Felix and Oscar of The Odd Couple. The fact that in the decades since people have come to view them as a gay couple says more about the normalization of homosexuality and the decline of the comic duo than anything intended by the Children’s Television Workshop.

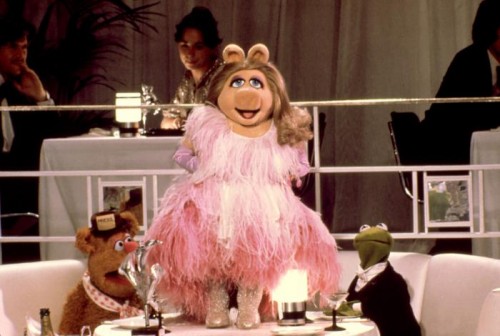

“They’re puppets,” explained Steve Whitmore, who’s performed Ernie since Henson’s death. “They don’t exist below the waist.” But denials have only added fuel to the fire. With a smirk, gay men enjoy “outing” these symbols of childhood with the same relish they used to reserve for “outing” Hollywood actors. With a continued dearth of same-sex role models in popular culture, Bert and Ernie have been enlisted as gay marriage symbols, appearing on placards, buttons, and t-shirts. Men dressed in Bert and Ernie costumes have even been married at gay pride parades. When it came to celebrating the Supreme Court’s ruling on the Defense of Marriage Act last June The New Yorker chose not an image of a flesh and blood couple but an illustration of the two Muppets cuddling.

It’s not just allies who suspect same-sex shenanigans at 123 Sesame Street.

“Bert and Ernie are two grown men sharing a house and a bedroom,” claimed the Reverend Joseph Chambers on his radio show. “They share clothes, eat and cook together and have blatantly effeminate characteristics… If this isn’t meant to represent a homosexual union, I can’t imagine what it’s supposed to represent.”

The Reverend clearly knows nothing of the show or, for that matter, fashion. Ernie has only ever worn horizontal stripes. Bert, being the more practical one, wears vertical, along with a very 1970’s turtleneck. As for being effeminate, Ernie is a disorganized mess while no stylish gay men would allow the caterpillar that stretches across Bert’s forehead to go un-tweezed.

Bert and Ernie sleep in separate beds, are rarely physical with each other, and never say lovey-dovey things. In fact, they seem ready to murder each other most of the time. (“Sounds like a lot of couples I know,” I can hear you saying.)

But everyone has it wrong. Bert and Ernie are meant to teach children they can be friends with people different from themselves. There’s nothing “gay” about them, save for Ernie’s love of bubble baths. If Reverend Chambers is really worried about kids being introduced to queer culture he needs to move past Bert and Ernie. He should condemn an entirely different show and an entirely different Muppet.

It was Miss Piggy who turned me gay.

Despite the celebrity cameos and pop culture spoofs, Sesame Street was always meant for children, but Jim Henson was wary of being seen as a kids’ entertainer. It took years for him to get it on the air but The Muppet Show, which ran from 1976 to 1981, was meant to correct this misconception. Henson sought to prove a show with puppets could have universal appeal.

Like Walt Disney and the creators of the Warner Brothers’ cartoons before them, Henson and his Muppet Workshop forgot to create female characters. (When a girl was needed on Sam and Friends, Henson’s first TV show, he’d throw a blonde wig on Kermit. If only Reverend Chambers had seen that!) There was the odd exception, such as a purple Muppet named Mildred who, with a perm and cat’s eye glasses, resembled a Fraggle librarian. But at the beginning The Muppet Show was an overwhelmingly male affair with male characters performed by male puppeteers. Like a true star Miss Piggy would have to invent herself.

The Muppet performers had used a homely lady-pig puppet in a few TV specials but she lacked a name and distinctive personality. Before the first season of The Muppet Show, Muppet designer Bonnie Erickson replaced the puppet’s beady black eyes with large blue ones and dressed her in a silk dress with lilac gloves. A permanently attached handkerchief was used to conceal the puppet’s arm rod. Paying tribute to Peggy Lee, Erickson named the puppet Miss Piggy Lee, but the “Lee” was swiftly dropped to avoid offending the singer.

Initially Miss Piggy lacked a distinctive voice. Frank Oz and Richard Hunt shared the responsibility of performing her, with the latter giving her a flouncy British accent and a stuffy, Margaret Dumont-ish character. But as Oz gradually took over, Miss Piggy’s personality asserted itself.

During one rehearsal, Henson and Oz were working on a scene in which Piggy slapped Kermit. Oz thought a karate chop was funnier, paired with a dramatic “hiii-yah!”

“Suddenly, that hit crystallized her character for me,” Oz told the New York Times. “The coyness hiding the aggression; the conflict of that love with her desire for a career; her hunger for a glamour image; her tremendous out-and-out ego…” As they say, a star was born.

Befitting a diva who stepped out of the chorus, Miss Piggy soon took over. With practically no other females to compete with (other than the androgynous guitarist Janice, originally designed as a big-lipped tribute to Mick Jagger) Piggy would grow in stature to become the only woman the Muppets needed. Her costumes multiplied. Her production numbers became more elaborate. She peppered her speech with ridiculous bastardizations of French, a habit perhaps inspired by the legendary Hollywood agent Sue Mengers. Miss Piggy thought nothing of throwing herself at male guest stars, or stealing scenes from great beauties like Raquel Welch.

Pigs, despite their documented intelligence, are thought of as dirty, rotund, and as far away from showbiz glamour as possible. But as a little kid I never took Miss Piggy as a joke. I accepted her beauty and elegance sincerely. For me, she was the star she believed herself to be. This was perfect training for my eventual love of drag queens, who also don sequined gowns, feather boas, and demand you take their star personae seriously.

Miss Piggy taught me that femininity and glamour are constructs. They are costumes anyone can wear providing you have the right attitude. I was a slightly effeminate little boy who collected My Little Ponies and owned a pair of Jelly sandals. Miss Piggy showed it was okay to be girly, that there was even power in being feminine.

Of course, simmering just below her fuzzy peach surface, Miss Piggy had a well of anger and aggression that busted out in karate chops, punches, and kicks. When she got mad, Frank Oz lowered her voice from its regular high-pitched coo to a low, gruff, streetwise snarl. Being a lady is all well and good, but when the going gets tough, the pig gets rough. A lilac glove can sometimes conceal a fist.

Miss Piggy is a pushy, bullying, manipulative, insecure, egoist. There’s more Diana Ross in her than Peggy Lee. She should be unlikeable.

But she has one trait that humanizes her. She loves Kermit. He’s her Achilles Hoof. Her love for him is pure, passionate, and pathetic. She humiliates herself over and over just to get his attention. As Frank Oz said, quoted in Brian Jay Johnson’s new biography of Jim Henson, “She wants that little green body so badly.” And Kermit, for the most part, brushes her off and ignores her. Loving someone incapable of reciprocating is a tragedy every queer person who’s fallen for a heterosexual can understand.

Miss Piggy eventually snagged Kermit via a surprise wedding at the end of The Muppets Take Manhattan (1984). The ceremony was performed by an actual New York City minister, and in the years since, puppets and performers alike have enjoyed teasing fans about whether the characters are “actually married” or not. Either way, the union of frog and pig and the nullification of their romantic tension brought a symbolic close to the Muppets’ Golden Age.

I love Miss Piggy, but I realize her characteristics as I’ve listed them aren’t exactly those of a role model. With her diva behavior and camp aesthetic, Miss Piggy is a throwback to the closeted gay world before the Stonewall Riots, when queer men worshipped Mae West and a sharp, sardonic tongue was their only weapon. By the time The Muppet Show was at its height, gay men had already moved on to body-building and Donna Summer. Perhaps this is why Pride Parades feature Bert and Ernie and not Miss Piggy. Miss Piggy, with her exaggerated femininity, barely concealed aggression, and pining love of a “straight” man, reminds gays of their past. Bert and Ernie as a committed couple is a more useful symbol for gay activists still fighting for same-sex marriage, even if it is a projection of fans. Puppeteers aren’t the only ones who can pull the strings.

Max Mosher is a freelance writer who has written for the Toronto Standard, WORN Fashion Journal, the Utne Reader, and Hello Mr. magazine. He tweets under @max_mosher_. Despite his best efforts, he’s more Kermit than Miss Piggy.