This guest post written by Allyson Johnson appears as part of our theme week on Ladies of the 1980s.

In any other film (9/10 times at least) just reading the synopsis of this movie would have greatly aggravated me and, to be frank, still did a little. There aren’t many films about women competing that paint the characters in question as anything more than shrewd, conniving and petty. Working Girl, much to my delight, doesn’t do that. Or, at least, it isn’t the main character’s objective. Hers is to simply find success and prove to herself and others that she has the talents and the skills to be more than what meets the mind.

The she in question is Tess McGill (Melanie Griffith), who lands a job as a secretary at a big company with a powerful woman, Katharine Parker (Sigourney Weaver) as her boss. At the start Tess is utterly enamored with Katherine, seeing her as a woman to look up to and admire, someone who has already achieved what she’s seeking and, in another film, I would have loved to see a buddy work comedy between the two, because who doesn’t want to be friends with Weaver? Of course, this isn’t to be because movies don’t like it when women are friends and instead, Katherine steals ones of Tess’s ideas and passes them as her own, leading Tess down a path of claiming her agency as a business woman looking to make a mark in the working world. What’s interesting is to see that despite her mounting disdain towards Katharine, Tess still adopts her mannerisms of how she operated in a work environment from the way she dresses and cuts her hair, playing a part to imbue herself with confidence she’s not sure she has yet. The difference is she’s coming at the role with a sense of selflessness and ambition, opposed to Katharine’s selfish nature.

Part of this is impacted by the actresses performances in the roles. Griffith who had been known for much more flightier characters brings a warm sense of empathy to Tess and a thread of naturalism as she too was undervalued as a performer until this Mike Nichols film gave her a bigger break out chance. Weaver, meanwhile, had at this point already played one of cinema’s greatest badasses in Ridley Scott’s Alien as Ripley, and her screen presence was one that captured attention; Weaver to this day is effortlessly enigmatic and it’s easy to understand why someone — real or fictional — would want to follow in her footsteps.

The contrast is one of the stronger aspects of the film which, to its benefit, never pits the characters against one another due to petty or contrived reasons. Tess is never aiming to purely undermine Katharine or trying to steal her position, but rather using Katharine’s absence to pursue her own career, even if it’s through dubious means.

The added element that solidifies the difference between Working Girl and other workplace dramedies — something that more fully flips the script?

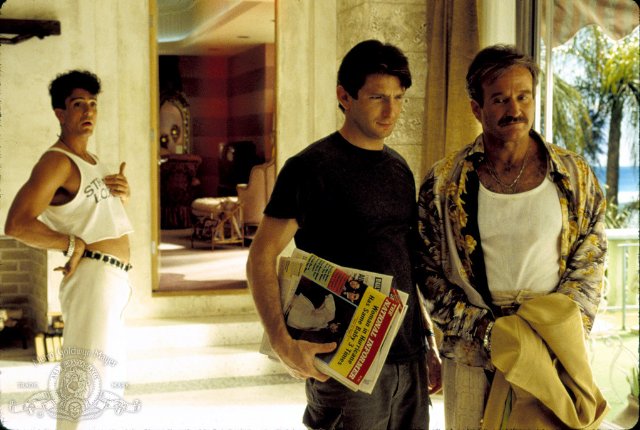

Enter Jack Trainer.

A film that understands Harrison Ford’s beauty (and, frankly, exploits it) and treats it as such is a winner in my book automatically (Raiders of the Lost Ark — hello) and late 80’s Ford was on a roll as it is in taking more challenging work with some of cinema’s greatest talents, Mike Nichols being a wonderful addition to that list. While he certainly isn’t played strictly for eye candy (that would be something) he is, in a way, played a “prize” between the two women while also having his own role to play. We so often view films through the Male Gaze with camera shots that are more interested in capturing the way a woman’s body looks under the guise of “sex sells” that it’s become somewhat of the norm. While Working Girl is appreciative of the beauty between Weaver and Griffith, it employs a “female gaze” so to speak with Ford. So much so that there’s a scene that goes to great lengths to express this as he changes in his office and women looking in through the window catcall and whistle.

Perhaps it’s not enough to turn convention on its head, but it’s a welcome change of pace.

Also a change of pace is the fact that by the end of the film, Katharine and Tess aren’t fighting over Jack. They’re fighting over their place in the working world and, to narrow it down to a single moment, they’re fighting over a great idea that Tess had, one Katharine wishes she could have come up with and resents Tess for.

I wouldn’t call Working Girl a feminist call to arms and this is largely due to how broadly Katherine’s character is painted towards the end of the film. At the start she’s written to be calculated, sure, but not the caricature that she becomes halfway through and if she’s distrustful of other employees there’s sense to that too, considering she’s found herself in a sea of suits, in a position of power that’s so at odds with what society had dictated she be. There’s reason to her hostility even but then, rather than exploring her further to make the dynamics between she and Tess more intriguing, the film takes the rather easier route and lets Katharine remain in the two dimensional realm with Weaver doing everything in her might to make her into something more.

Add to that the lack of diversity and there was definitely room to grow — a lot of room.

Writer Kevin Wade and director Mike Nichols crafted a film that is both celebratory of the female experience while also skewering the system that placed them in gendered boxes in the first place. The biggest success of the film isn’t the romance or the drama, but the implications of what lead the characters to their positions in the first place. Katharine fought for the position she has and Tess fought to catch up and achieve the same goal. It’s imperfect, but ambitious, just like its leading ladies.

See also at Bitch Flicks: The Corporate Catfight in ‘Working Girl’; ‘Working Girl’ Is ‘White Feminism: The Movie’

Allyson Johnson is a 20-something living in the Boston area. She’s the Film Editor for TheYoungFolks.com and her writing can also be found at The Mary Sue and Cambridge Day. Follow her on Twitter for daily ramblings, feminist rants, and TV chat @AllysonAJ.