Forbes recently published a

list of Hollywood’s top-earning actresses, for films completed within the previous year.

Please note the following:

“As is still typical for Hollywood, our actresses earned significantly less than their male counterparts. Harrison Ford was the top-earning actor this year with $65 million, $38 million more than Jolie earned. All told, the top 10 actors earned $393 million, compared with $183 million for the top 10 actresses.”

Take a look at the 15 Top-Earning Actresses, along with their respective career Oscar wins and Oscar nominations (as of 2009).

1. Angelina Jolie: $27 million

1 Oscar win, 2 Oscar nominations

2. Jennifer Aniston: $25 million

0 Oscar wins, 0 Oscar nominations

3. Meryl Streep: $24 million

2 Oscar wins, 15 Oscar nominations

4. Sarah Jessica Parker: $23 million

0 Oscar wins, 0 Oscar nominations

5. Cameron Diaz: $20 million

0 Oscar wins, 0 Oscar nominations

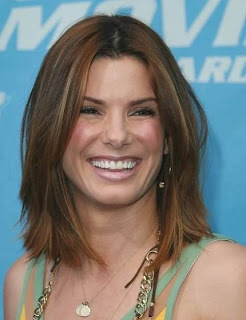

6. Sandra Bullock (tie): $15 million

0 Oscar wins, 0 Oscar nominations

7. Reese Witherspoon (tie): $15 million

1 Oscar win, 1 Oscar nomination

8. Nicole Kidman (tie): $12 million

1 Oscar win, 2 Oscar nominations

9. Drew Barrymore (tie): $12 million

0 Oscar wins, 0 Oscar nominations

10. Renee Zellweger: $10 million

1 Oscar win, 3 Oscar nominations

11. Cate Blanchett: $8 million

1 Oscar win, 4 Oscar nominations

12. Anne Hathaway (tie): $7 million

0 Oscar wins, 1 Oscar nomination

13. Halle Berry (tie): $7 million

1 Oscar win, 1 Oscar nomination

14. Scarlett Johansson: $5.5 million

0 Oscar wins, 0 Oscar nominations

15. Kate Winslet: $2 million

1 Oscar win, 6 Oscar nominations

Total Amount of Money Earned: $212.5 million

Total Number of Oscar Nominations: 35

Total Number of Oscar Wins: 9

***************************************************************

And, just for kicks, here’s the Forbes list of the 15 Top-Earning Actors:

1. Harrison Ford: $65 million

(0 Oscar wins, 1 Oscar nomination)

2. Adam Sandler: $55 million

(0 Oscar wins, 0 Oscar nominations)

3. Will Smith: $45 million

(0 Oscar wins, 2 Oscar nominations)

4. Eddie Murphy (tie): $40 million

(0 Oscar wins, 1 Oscar nomination)

5. Nicolas Cage (tie): $40 million

(1 Oscar win, 2 Oscar nominations)

6. Tom Hanks: $35 million

(2 Oscar wins, 5 Oscar nominations)

7. Tom Cruise: $30 million

(0 Oscar wins, 3 Oscar nominations)

8. Jim Carrey (tie): $28 million

(0 Oscar wins, 0 Oscar nominations)

9. Brad Pitt (tie): $28 million

(0 Oscar wins, 2 Oscar nominations)

10. Johnny Depp: $27 million

(0 Oscar wins, 3 Oscar nominations)

11. George Clooney: $25 million

(for acting: 1 Oscar win, 2 Oscar nominations)

12. Russell Crowe (tie): $20 million

(1 Oscar win, 3 Oscar nominations)

13. Robert Downey Jr. (tie): $20 million

(0 Oscar wins, 2 Oscar nominations)

14. Denzel Washington (tie): $20 million

(2 Oscar wins, 5 Oscar nominations)

15. Vince Vaughn: $14 million

(0 Oscar wins, 0 Oscar nominations)

Total Amount of Money Earned: $492 million

Total Number of Oscar Nominations: 31

Total Number of Oscar Wins: 7

***************************************************************

In the past year, the top-earning men made over twice the amount of money as the top-earning women. Perhaps the Oscar info might seem arbitrary; the films that usually gross the most money (summer blockbusters, Apatow, etc) don’t necessarily line up with the many low-budget films that garner Oscar nominations for the performances (The Reader, Rachel Getting Married).

But I still find it disheartening, to say the least, to look at a list where the highest paid women in the previous year, who have won more Oscars overall (arguably the most prestigious award in the history of fucking filmmaking), and who have been nominated for more Oscars overall, still earned less than half of what their male counterparts earned.

***************************************************************

Now, to get really super-crazy, let’s look at the highest grossing films that the top five earning actors and actresses released last year, specifically noting who starred, the exact box office gross, and the overall “fresh” rating on rotten tomatoes (a high percentage means critics thought it rocked; anything lower than 60% usually means it was a piece of shit).

Actresses

1. Angelina Jolie: Kung Fu Panda

Box Office: $215,395,021

RT Rating: 89%

2. Jennifer Aniston: Marley & Me

Box Office: $143,084,510

RT Rating: 61%

3. Meryl Streep: Mamma Mia!

Box Office: $143,704,210

RT Rating: 53%

4. Sarah Jessica Parker: Sex and the City

Box Office: $152,595,674

RT Rating: 50%

5. Cameron Diaz: What Happens in Vegas

Box Office: $80,199,843

RT Rating: 27%

Total Box Office Gross: $734,979,258

Average RT Rating: 56%

Actors

1. Harrison Ford: Indiana Jones … Crystal Skull

Box Office: $316,957,122

RT Rating: 76%

2. Adam Sandler: Bedtime Stories

Box Office: $109,993,847

RT Rating: 23%

3. Will Smith: Hancock

Box Office: $227,946,274

RT Rating: 39%

4. Eddie Murphy: Meet Dave

Box Office: $11,644,832

RT Rating: 19%

5. Nicolas Cage: Knowing

Box Office: $79,911,877

RT Rating: 32%

Total Box Office Gross: $746,453,952

Average RT Rating: 38%

***************************************************************

Basically, the women made much better films according to critics. And while the men grossed more at the box office, by $11.5 million, it’s hardly worth mentioning when you’re talking about $746 million versus $735 million. And yet, the top five actors still earned more than double ($245 million) what the top five actresses earned ($119 million).

Will someone please explain to me how this isn’t blatant gender-based discrimination?