Tag: Women in Hollywood

Wedding Week: ‘My Best Friend’s Wedding’ Is a Right-Wing Nightmare Interpretation of Women

|

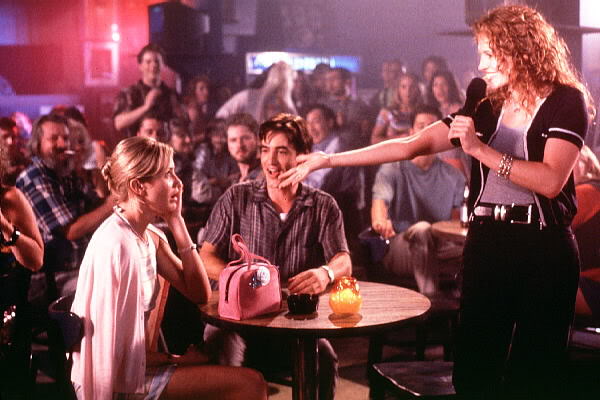

| Julia Roberts in My Best Friend’s Wedding |

|

| Someone nicely made a collage of all this. |

|

| Julianne cruelly forces a terrified Kimmy into singing karaoke. |

|

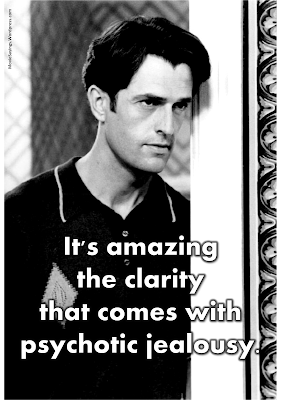

| “It’s amazing the clarity that comes with psychotic jealousy,” George says to Julianne. |

|

| Kimmy confronts Julianne in the ladies room where we are reminded that POC do exist. |

Wedding Week: ‘Sex and the City’: The Movie We Hate to Love

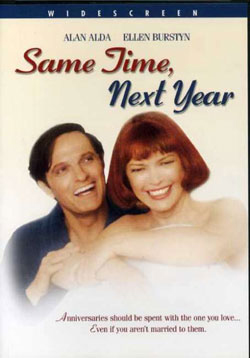

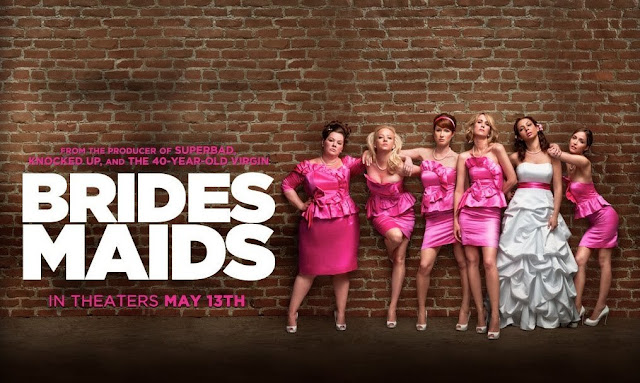

Wedding Week: Why We All Need to See ‘Bridesmaids’

|

| Movie poster for Bridesmaids |

|

| Maya Rudolph and Kristen Wiig exercising in Bridesmaids |

| Drinks, pre-food poisoning, in Bridesmaids |

|

| Bridesmaids karaoke |

|

| Kristen Wiig in Bridesmaids |

|

| The ladies of Bridesmaids |

|

| A sweaty Kristen Wiig in Bridesmaids |

8. They also talk like real-life women. Like the rest of us, they talk about everything in life … they talk about their jobs, their life choices, their regrets, their bodies, their friendships, other women, their hopes and dreams, and, yes, their clothes and even sometimes men. But they don’t ONLY talk about men, which is crucial.

|

| Kristen Wiig’s airplane freakout in Bridesmaids |

|

| Annie Mumolo and Kristen Wiig in Bridesmaids |

So what are you waiting for?

Wedding Week: ‘Bride Wars’: When Weddings Drive a Bitch Crazy

In Gary Winick’s 2009 film Bride Wars, two best friends pit themselves against each other in order to both have their dream wedding day. If this thoroughly unfeminist – not to mention unlikely – premise doesn’t put you off then pull on your spanx, pin up your hair, and settle in to enjoy some fun so light and frothy it may as well be a specially designed valium-laced cupcake.

It pains me to state that a rare successful Hollywood film featuring a rare two female leads (Kate Hudson and Anne Hathaway) orientates itself around the wedding industry, an industry that feeds on female insecurity, causing otherwise sane and sensible women to spend a fortune on a single day in a quest for a level of perfection that probably only exists on cinema screens.

|

| Best friends turned worst enemies |

It also pains me to admit that the film is a firm favourite of mine because the lunacy that is fused to its girliness means it fits very well into that hallowed space known as “comfort movie.” Feel free to judge. I know you have one too.

Written by the female comedy duo Casey Wilson and June Diane Raphael, Bride Wars can be read as a much lighter companion piece to Kristen Wiig’s infinitely dirtier Bridesmaids, were Wiig’s depiction of how women behave when their closest friendship is self-immolating not far more realistic (yes, I do include the part where she hallucinates on the plane) and – let’s be real – funnier.

Bride Wars depicts both its brides – friends since childhood – as beautiful, successful in their careers and in stable relationships. It also depicts their descent into venomous harpies when it emerges that their wedding planner (a dignified and ice-cool Candace Bushnell) has booked both of their weddings to take place at Manhattan’s Plaza Hotel on the same day.

The Plaza, we understand, has been both of the women’s dream venue since childhood visits with their mothers, who were also BFFs. This may be a side issue but, realistically, how many women’s best childhood friend remains their closest friend into adulthood, particularly when they became friends because of their mothers’ friendship?

Also, how realistic is it that both of these women would remain fixated on the goddamn Plaza from the age of six through twenty-six? Yes, the Palm Court is divine but I maintain that at some point at least one of them – probably Hathaway whose character Emma is a teacher – would have looked round and said, “You know? I don’t think it really is worth the money.”

|

| Liv in Vera Wang |

Bride Wars, then, is a film about madness. Emma and Liv (Hudson) are arguably experiencing a folie a deux bought on by that well-known contagious disease, wedding fever. Since before the Great Depression there have been studies showing that even in times of dire need, people in the West will still spend the equivalent of a down payment on a home on their weddings. Tell me that’s not crazy.

Bride Wars is a film that aims to capture its audience, which I think we can take for granted is made up entirely of women, by highlighting the worst side of what Hollywood likes to depict as the nature of women. Rather than solving their planner’s error in a dignified, or even organized way, the brides turn on each other, exploiting each other’s vulnerabilities and weaknesses in ways that only a former ally ever can.

And though it’s amusing to watch the pair go at each other in increasingly underhanded ways – a dye job gone brutally wrong, a fake tan turned neon, deliveries of cakes and sweets causing one bride to gain so much weight that she can no longer fit into her bridal gown, a Bachelorette crashed and dance-off performed – there is also the fact that these acts have consequences so far-reaching that it’s hard to imagine the pair hugging out at the end of the film (which, of course, they do).

Liv’s dress, for example, was by Vera Wang, meaning it probably cost in the region of $25,000. That’s a lot of money to make a former friend waste. The bad dye job turned her locks blue, causing a disastrous day at work that very nearly costs her the job that’s paying for that fancy frock and, one suspects, her wedding as her fiancé is shown to earn less money than her.

But worse than all of this is the fact that, while the women go at each other like thirteen-year-olds with enough money to act out their most schadenfreude-filled fantasies, the men in it are doing nothing. Not strictly nothing. Both the grooms have jobs and seem like OK dudes, but neither of them is running around the city in a vengeful huff because his soon-to-be-wife’s former-bestie is trying to best their wedding day and destroy his woman’s life.

|

| The madness at work |

No, in Bride Wars that brand of madness is entirely female. This says nothing good or particularly realistic about the state of mind of the modern adult female. I mean, yes, we get hurt and pissed off when our friends do something that seems designed to cause pain to us, but how many of us who are not mentally ill follow them around, actively trying to ruin one of the most significant and expensive days of their lives?

For one thing, who would have time, especially if they were trying to plan the happiest day of their own lives at the same time?

So, once again, even though I doubt the writers were trying to make a serious point about how the pressure and expectations of the wedding industry can direly affect women’s mental states, I think the film is about mental illness. You decide.

Alisande Fitzsimons is a writer and stylist from Dublin. She can be found tweeting about weddings and clothes @AlisandeF.

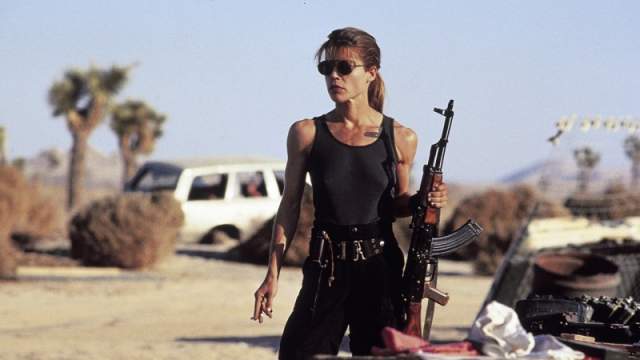

Where Have You Gone, Sarah Connor?

|

| Remember Linda Hamilton (playing Sarah Connor) and her guns in Terminator 2? |

|

| Anne Hathaway as Catwoman |

|

| Ellen Ripley |

Thelma and Louise had a big reaction, there was a huge thing at the time, that, ‘Oh my god, these women had guns and they actually killed a guy!’ … That movie made me realize—you can talk about it all you want, but watch it with an audience and talk to women who have seen this movie and they go, ‘YES!’ They feel so adrenalized and so powerful after seeing some women kick some ass and take control of their own fate. … Women go, ‘Yeah – fucking right!’ Women don’t get to have that experience in the movies. But hey, people go to action movies for a reason; they want to feel adrenalized and they want to identify with the hero, and if only guys get to do that then it’s crazy.

Sarah Polley’s ‘Stories We Tell’: A Radical Act

|

| Movie poster for Stories We Tell |

So, how do we define “real” anymore or, for that matter, what is “true”?

|

| Polley and her father in Stories We Tell |

Mary Jo Murphy gives some background on the film in her New York Times review:

A bit more about “the story”: Ms. Polley is the youngest of five siblings. Dad was an English actor in Toronto; Mom, an actress, had two children from a marriage before she met him. She died of cancer when Sarah was 11, and at some point after that, one or more of her much older siblings began to tease her about her paternity. Eventually she did a little investigating.

When she found her answer, and talked to her father and siblings about it, she became fascinated with how each of them was “telling the story and embellishing the story and making the story their own.” The act of telling the story, she said, “was changing the story itself.”

|

| Polley’s father in Stories We Tell |

Polley is making a film about her father, her late mother, her siblings. She should protect them. What she shouldn’t do is offer up the resulting feel-good whitewash to the scrutiny of a watching world. She shouldn’t force on strangers the task of sitting through this. And she shouldn’t present a work of vanity and closed-in narcissism as an exercise in soul baring, because it’s embarrassing for everybody.

|

| Polley’s mother and father in Stories We Tell |

Leigh Kolb wrote a piece for Bitch Flicks last November called, “Female Literacy as a Historical Framework for Hollywood Misogyny” in which she suggested that, “When women finally break through and are able to tell their stories, those stories are immediately dismissed as silly and trivial.” She goes on to say:

Perhaps this bleak, largely anti-feminist landscape in Hollywood is more deliberate. If we acknowledge women’s long history of being neglected education and literacy, and that women have been repeatedly told (or observed) that their stories lack action and intrigue for a broad audience, how can this not have larger social effects? And at some point, do we come to the conclusion that these messages are what the dominant group wants?

|

| Polley’s mother in Stories We Tell |

|

| Sarah Polley, badass |

Summer Movie Preview

|

| Spaceship! *starts salivating* |

|

| Seriously, read the book. |

‘Stoker’: The Creepiest Coming-of-Age Tale I’ve Ever Seen

|

| Stoker movie poster |

|

| Uncomfortable mother-daughter interaction |

It’s hard to avoid spoilers at this point, but let’s leave it at this: India discovers that her parents have been concealing something very important regarding her uncle—and, given her emotionally close relationship with him, something very important about herself, about character traits that are a part of her own blood. When the truth comes out, her world is overturned, her monsters are unleashed, and she finds herself without the solid footing of character, self-knowledge, and moral clarity to fight them.

|

| Evie (Nicole Kidman) and India (Mia Wasikowska) |

|

| Saddle Shoe (girlhood!) and High Heel (womanhood!) |

|

| Evie loses her shit on India (finally!) |

|

| Goodbye, Auntie Gin |

|

| Evie and Charlie (Matthew Goode) |

|

| India imitating a yard statue, accompanied by saddle shoes |

|

| These fucking shoes! |

|

| I’m sure this is a 100% acceptable uncle-niece interaction |

|

| India as Hunter |

2013 Oscar Week: The Roundup

Academy Awards Commentary:

“Oscar Hosts Preferable to Seth MacFarlane: An Abbreviated List” by Robin Hitchcock

“This Needs No Explanation” by Stephanie Rogers

“Fun with Stats: Best Actor/Actress Nominations vs. Best Picture Nominations” by Robin Hitchcock

“5 People Who Should Host the Oscars at Some Point” by Lady T

“Fun with Stats: Winners of Oscars for Acting by Age” by Robin Hitchcock

“2013 Academy Awards Diversity Checklist” by Lady T

“Race and the Academy: Black Characters, Stories and the Danger of Django“ by Leigh Kolb

“5 Female-Directed Films That Deserved Oscar Nominations” by James Worsdale

“Best Actress Nominee Rundown” by Rachel Redfern

“Feminism and the Oscars: Do This Year’s Best Picture Nominees Pass the Bechdel Test?” by Megan Kearns

“Academy Documentaries: People’s Stories, Men’s Voices” by Jo Custer

Amour: nominated for Best Picture; Best Actress, Emmanuelle Riva; Best Director, Michael Haneke; Best Foreign Language Film; Best Original Screenplay, Michael Haneke

Amour: nominated for Best Picture; Best Actress, Emmanuelle Riva; Best Director, Michael Haneke; Best Foreign Language Film; Best Original Screenplay, Michael Haneke

“Best Actress Nominee Rundown” by Rachel Redfern

Life of Pi: nominated for Best Picture; Best Cinematography, Claudio Miranda; Best Director, Ang Lee; Best Film Editing, Tim Squyres; Best Original Score, Mychael Danna; Best Original Song, Mychael Danna, Bombay Jayashri; Best Production Design, David Gropman, Anna Pinnock; Best Sound Editing, Eugene Gearty, Philip Stockton; Best Sound Mixing, Ron Bartlett, D.M. Hemphill, Drew Kunin; Best Visual Effects, Bill Westenhover, Guillaume Rocheron, Erik-Jan De Boer, Donald R. Elliott; Best Adapted Screenplay, David Magee

Argo: nominated for Best Picture; Best Supporting Actor, Alan Arkin; Best Film Editing, William Goldenberg; Best Original Score, Alexandre Desplat; Best Sound Editing, Erik Aadahl, Ethan Van der Ryn; Best Sound Mixing, John Reitz, Gregg Rudloff, Jose Antonio Garcia; Best Adapted Screenplay, Chris Terrio

“Does Argo Suffer from a Woman Problem and Iranian Stereotypes?” by Megan Kearns

Lincoln: nominated for Best Picture; Best Actor, Daniel Day-Lewis; Best Supporting Actor, Tommy Lee Jones; Best Supporting Actress, Sally Field; Best Cinematography, Janusz Kaminski; Best Costume Design, Joanna Johnston; Best Director, Steven Spielberg; Best Film Editing, Michael Kahn; Best Original Score, John Williams; Best Production Design, Rick Carter, Jim Erickson; Best Sound Mixing, Andy Nelson, Gary Rydstrom, Ronald Judkins; Best Adapted Screenplay, Tony Kushner

“In Praise of Sally Field As Mary Todd Lincoln” by Robin Hitchcock

Beasts of the Southern Wild: nominated for Best Picture; Best Actress, Quvenzhané Wallis; Best Director, Benh Zeitlin; Best Adapted Screenplay, Lucy Alibar, Benh Zeitlin

“Best Actress Nominee Rundown” by Rachel Redfern

“Beasts of the Southern Wild: Gender, Race and a Powerful Female Protagonist in the Most Buzzed About Film” by Megan Kearns

“Beasts of the Southern Wild: I Didn’t Get It” by Robin Hitchcock

“Cosmology, Gender, and Quvenzhané Wallis: Beasts of the Southern Wild“ by Max Thornton

“Beasts of the Southern Wild: Deluge Myths” by Laura A. Shamas

Silver Linings Playbook: nominated for Best Picture; Best Actor, Bradley Cooper; Best Actress, Jennifer Lawrence; Best Supporting Actor, Robert De Niro; Best Supporting Actress, Jacki Weaver; Best Director, David O. Russell; Best Film Editing, Jay Cassidy, Crispin Struthers; Best Adapted Screenplay, David O. Russell

“Best Actress Nominee Rundown” by Rachel Redfern

“Silver Linings Playbook, or, As I Like to Call It: fuckyeahjenniferlawrence” by Stephanie Rogers

Django Unchained: nominated for Best Picture; Best Supporting Actor, Christoph Waltz; Best Cinematography, Robert Richardson; Best Sound Editing, Wylie Stateman; Best Original Screenplay, Quentin Tarantino

“From a Bride with a Hanzo Sword to a Damsel in Distress: Did Quentin Tarantino’s Feminism Take a Step Backwards in Django Unchained?” by Tracy Bealer

“Heroic Black Love and Male Privilege in Django Unchained“ by Joshunda Sanders

“The Power of Narrative in Django Unchained“ by Leigh Kolb

“Race and the Academy: Black Characters, Stories and the Danger of Django“ by Leigh Kolb

Zero Dark Thirty: nominated for Best Picture; Best Actress, Jessica Chastain; Best Film Editing, Dylan Tichenor, William Goldenberg; Best Sound Editing, Paul N.J. Ottosson; Best Original Screenplay, Mark Boal

“Best Actress Nominee Rundown” by Rachel Redfern

“Jessica Chastain’s Performance Propels the Exquisitely Sharp But Aloof Zero Dark Thirty“ by Candice Frederick

“Zero Dark Thirty Raises Questions on Gender and Torture, Gives No Easy Answers” by Megan Kearns

“The Zero Dark Thirty Controversy: What Does Jessica Chastain’s Beauty Have to Do With It?” by Lady T

“Maya from Zero Dark Thirty Is an Emotional Character” by Alison Vingiano

Les Misérables: nominated for Best Picture; Best Actor, Hugh Jackman; Best Supporting Actress, Anne Hathaway; Best Costume Design, Paco Delgado; Best Makeup and Hairstyling, Lisa Westcott, Julie Dartnell; Best Original Song, Claude-Michel Schonberg, Herbert Kretzmer, Alain Boublil; Best Production Design, Eve Stewart, Anna Lynch-Robinson; Best Sound Mixing, Andy Nelson, Mark Paterson, Simon Hayes

“Extreme Weight Loss for Roles Is Not ‘Required’ and Not Praiseworthy” by Robin Hitchcock

“Les Misérables: The Feminism Behind the Barricades” by Leigh Kolb

“Les Misérables, Sex Trafficking & Fantine as a Symbol for Women’s Oppression” by Megan Kearns

“Les Misérables: Some Musicals Are More Feminist Than Others” by Natalie Wilson

Flight: nominated for Best Actor, Denzel Washington; Best Original Screenplay, John Gatins

“The Women in Whip Whitaker’s Life: Representations of Female Characters in Flight“ by Martyna Przybysz

“Flight‘s Unintentional Pro-Woman Message” by Lady T

The Impossible: nominated for Best Actress, Naomi Watts

“Best Actress Nominee Rundown” by Rachel Redfern

“It’s ‘Impossible’ Not to See the White-Centric Point of View” by Lady T

The Master: nominated for Best Actor, Joaquin Phoenix; Best Supporting Actor, Philip Seymour Hoffman; Best Supporting Actress, Amy Adams

“The Master: A Movie About White Dudes Talking About Stuff” by Stephanie Rogers

The Sessions: nominated for Best Supporting Actress, Helen Hunt

“On Sex, Disability, and Helen Hunt in The Sessions“ by Stephanie Rogers

“The Transformative Journey of Sex in The Sessions“ by Rachel Redfern

“Depicting Sex Surrogacy in The Sessions“ by Alisande Fitzsimons

Brave: nominated for Best Animated Film

“Why I’m Excited About Pixar’s Brave & Its Kick-Ass Female Protagonist … Even If She Is Another Princess” by Megan Kearns

“Will Brave‘s Warrior Princess Merida Usher in a New Kind of Role Model for Girls?” by Megan Kearns

“The Princess Archetype in the Movies” by Laura A. Shamas

“Brave and the Legacy of Female Prepubescent Power Fantasies” by Amanda Rodriguez

Frankenweenie: nominated for Best Animated Film

ParaNorman: nominated for Best Animated Film

“The Brainy Message of ParaNorman“ by Natalie Wilson

The Pirates! Band of Misfits: nominated for Best Animated Film

Wreck-It Ralph: nominated for Best Animated Film

“Wreck-It Ralph Is Flawed But Still Pretty Feminist” by Myrna Waldron

Anna Karenina: nominated for Best Cinematography, Seamus McGarvey; Best Costume Design, Jacqueline Durran; Best Original Score, Dario Marianelli; Best Production Design, Sarah Greenwood, Katie Spencer

“Anna Karenina, and the Tragedy of Being a Woman in the Wrong Era” by Erin Fenner

5 Broken Cameras: nominated for Best Documentary

“Academy Documentaries: People’s Stories, Men’s Voices” by Jo Custer

The Gatekeepers: nominated for Best Documentary

“Academy Documentaries: People’s Stories, Men’s Voices” by Jo Custer

How to Survive a Plague: nominated for Best Documentary

“How to Survive a Plague: When Aging Itself Becomes a Triumph” by Ren Jender

“Acting Up: A Review of How to Survive a Plague“ by Diana Suber

“Academy Documentaries: People’s Stories, Men’s Voices” by Jo Custer

The Invisible War: nominated for Best Documentary

“The Invisible War Takes on Sexual Assault in the Military” by Soraya Chemaly

“Academy Documentaries: People’s Stories, Men’s Voices” by Jo Custer

Mirror Mirror: nominated for Best Costume Design, Eiko Ishioka

“Trailers for Snow White & the Huntsman and Mirror Mirror Perpetuate Stereotypes of Women, Beauty & Aging and Pit Women Against Each Other” by Megan Kearns

“Happily Never After: The Sad (and Sexist?) Rush to Cast Some of Our Most Promising Young Actresses as Fairy Tale Princesses” by Scott Mendelson

Searching for Sugar Man: nominated for Best Documentary

“Searching for Sugar Man Makes Race Invisible” by Robin Hitchcock

“Academy Documentaries: People’s Stories, Men’s Voices” by Jo Custer

Skyfall: nominated for Best Cinematography, Roger Deakins; Best Original Score, Thomas Newman; Best Original Song, Adele Adkins, Paul Epworth; Best Sound Editing, Per Hallberg, Karen Baker Landers; Best Sound Mixing, Scott Millan, Greg P. Russell, Stuart Wilson

“The Sun (Never) Sets on the British Empire: The Neocolonialism of Skyfall“ by Max Thornton

“Skyfall: It’s M’s World, Bond Just Lives in It” by Margaret Howie

Snow White and the Huntsman: nominated for Best Costume Design, Colleen Atwood; Best Visual Effects, Cedric Nicolas-Troyan, Philip Brennan, Neil Corbould, Michael Dawson

“Trailers for Snow White & the Huntsman and Mirror Mirror Perpetuate Stereotypes of Women, Beauty & Aging and Pit Women Against Each Other” by Megan Kearns

“Snow White and the Huntsman: A Better Role Model?” by Allison Heard

“Happily Never After: The Sad (and Sexist?) Rush to Cast Some of Our Most Promising Young Actresses as Fairy Tale Princesses” by Scott Mendelson

“A Feminist Review of Snow White and the Huntsman“ by Rachel Redfern

“The Princess Archetype in the Movies” by Laura A. Shamas

“Matriarchal Impositions of Beauty in Snow White and the Huntsman“ by Carleen Tibbets

Chasing Ice: nominated for Best Original Song, J. Ralph

A Royal Affair: nominated for Best Foreign Language Film (Denmark)

“A Royal Affair“ by Rosalind Kemp

“More Royal Than Affair” by Atima Omara-Alwala

Hitchcock: nominated for Best Makeup and Hairstyling, Howard Berger, Peter Montagna, Martin Samuel

“Too Many Hitchcocks” by Robin Hitchcock

“Hitchcock Turns the Master of Suspense into a Real Life Dud” by Candice Frederick

The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey: nominated for Best Makeup and Hairstyling, Peter Swords King, Rick Findlater, Tami Lane; Best Production Design, Dan Hennah, Ra Vincent, Simon Bright; Best Visual Effects, Joe Letteri, Eric Saindon, David Clayton, R. Christopher White

“The Hobbit: A Totally Expected Bro-Fest” by Erin Fenner

“The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey: The Addition of Feminine Presence During a Quest for the Ages” by Elise Schwartz

No: nominated for Best Foreign Language Film (Chile)

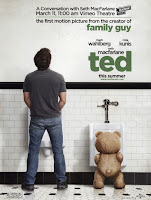

Ted: nominated for Best Original Song, Walter Murphy, Seth MacFarlane

“Damning Ted with Faint Praise” by Robin Hitchcock

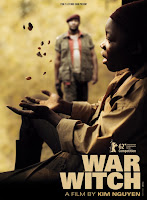

War Witch: nominated for Best Foreign Language Film (Canada)

“A Thorn Like a Rose: War Witch (Rebelle)“ by Emily Campbell

Kon Tiki: nominated for Best Foreign Language Film (Norway)

The Avengers: nominated for Best Visual Effects, Janek Sirrs, Jeff White, Guy Williams, Dan Sudick

“The Avengers, Strong Female Characters and Failing the Bechdel Test” by Megan Kearns

“The Avengers: Are We Exporting Media Sexism or Importing It?” by Soraya Chemaly

“Quote of the Day: Scarlett Johansson Tired of Sexist Diet Questions” by Megan Kearns

Moonrise Kingdom: nominated for Best Original Screenplay, Wes Anderson, Roman Coppola

“An Open Letter to Owen Wilson Regarding Moonrise Kingdom“ by Molly McCaffrey

Prometheus: nominated for Best Visual Effects, Richard Stammers, Trevor Wood, Charley Henley, Martin Hill

“Is Prometheus a Feminist Pro-Choice Metaphor?” by Megan Kearns

“A Feminist Review of Prometheus“ by Rachel Redfern

“Prometheus and the Alien Movies: Feminism and Anti-Feminism” by Rhea Daniel

Documentary Short Film: nominees include Inocente, Kings Point, Mondays at Racine, Open Heart, Redemption

Animated Short Film: nominees include Adam and Dog, Fresh Guacamole, Head over Heels, Paperman, Maggie Simpson in “The Longest Daycare”

Short Live Action Film: nominees include Asad, Buzkashi Boys, Curfew, Death of a Shadow (Dood van een Schaduw), Henry

Guest Writer Wednesday: "Girls Make Movies Too": Riding on Kim Swift’s Call to Arms

Let’s All Take a Deep Breath and Calm the Fuck Down About Lena Dunham

|

| Lena Dunham and the cast of Girls |

Written by Stephanie Rogers.

I have yet to hear anyone react to the news of an advance with, “Yep, that seems about right.” It would be great if the writers and books that deserved the most money got it—ditto the same amount of attention and praise. And all the gripe-storming about how slight her book proposal was, and how she’ll never make back her advance—when did we start reviewing book proposals? When did writers start caring so passionately about publishers recouping their losses?

The entertainment industry is not a meritocracy. From before the days of Barrymore to our present age of Bacons and Bridges, Sheen-Estevezes and Zappas family has, for better and worse, equaled opportunity. The Coppola family’s connections and influence are so vast they’d make the mob envious.

I hear the diversity criticism. However, to suggest that “Girls”—a show whose charm lies in part in its documentary-like feel—presents the universe these young women inhabit, working in publishing and the arts, as rich in racial diversity, would be, sadly, to lie. Besides, did anyone ever kvetch about Jerry Seinfeld’s lack of Asian friends?

It’s cute (read: pretty hypocritical, actually) to see this sudden spike in concern over television’s portrayal of women, but this fixation is propelled by the same sense of threatened dudeness that makes a show written by and about women so “controversial” in the first place. If television were an even playing field, Dunham would not be on the cover of New York magazine atop the subheading “Girls is the ballsiest show on TV,” nor would the debut of this series be such a massive deal. (Where are the cultural dissections of CSI: Miami?) The critics calling Girls disingenuous because it stars four white women should redirect their frustration toward misogyny itself, not at the one show trying to fight it.

|

| Lena Dunham, probably getting ready to annoy people with her incessant whining |

Admittedly, I have a soft spot for Dunham, having written about her wonderful film Tiny Furniture way back in 2011, before she’d manage to offend the entire nation with her giant thighs and sloppy backside. I think she comes across as genuinely funny and interesting, and I hope that her success—and the hard hits she’s taking because of it—will make the next woman who dares to step out of line (where “line” means “the patriarchal framework”) do so with just as much fearlessness.

I mean, it’s not going to be like, “Hey guys, we’ve been out looking for a black friend or a friend in a wheelchair or a friend with a hat.” The tough thing is you kind of can’t win on that one. I have to write people who feel honest but also push our cultural ball forward.

Here’s what I think, after watching the first half hour of the season: I admire that Dunham took the criticism she got last year to heart. There are so many examples of how Hollywood ignores this type of thing. In fact, there are whole websites devoted to it. It really seems like she listened; I can’t tell from thirty minutes that everything has been solved, but it seems to be off to a good start? Lena Dunham isn’t so bad? Maybe? I say that with reservation but enthusiasm. Before I go, a couple thoughts on the good and the bad:

Good: I’ll start with positive reinforcement: Girls is definitely more diverse this season!

Bad: That definitely wasn’t the hardest thing to do.

Good: Donald Glover as Sandy! Hannah’s new, fleshed-out, not at all T-Doggy boyfriend.

Bad: I’m just hoping Donald Glover won’t simply be this show’s Charlie Wheeler.

Good: About the extras: A marked improvement in the representation of Brooklyn’s racial mix. So, Lena Dunham created a popular show, a critically acclaimed show, and instead of being, like, “Whatever. They’re all going to watch me anyway!” she actually made an effort to improve her show. That’s good. Very good. And to be honest, she probably realizes that a more realistic mix equals a more realistic world for her characters to live in.

Bad: Again, this is about the extras: There are definitely more black people on the show, but … I mean … I’ll put it this way. Realistic diversity is definitely not in your first season, girl. But it also not this. It’s definitely realistic here. But—it’s not this either, so don’t go overboard.

|

| White Women |

Laura Bennett at The New Republic said this:

Dunham uses the Sandy plot line as an opportunity to skewer both the complaints of her critics—Hannah herself echoes them with the misguided assumption that her essays are “for everyone”—and her characters’ blinkered worldview. Glover’s arc on the show is brief, but he is key to illustrating the limited scope of Hannah’s experience. “This always happens,” Sandy tells Hannah during their fight. “I’m a white girl and I moved to New York and I’m having a great time and oh I’ve got a fixed gear bike and I’m gonna date a black guy and we’re gonna go to a dangerous part of town. All that bullshit. I’ve seen it happen. And then they can’t deal with who I am.” Hannah responds with an explosion of goofy knee-jerk progressivism: “You know what, honestly maybe you should think about the fact that you could be fetishizing me. Because how many white women have you dated? Maybe you think of us as one big white blobby mass with stupid ideas. So why don’t you lay this thing down, flip it, and reverse it.” “You just said a Missy Elliot lyric,” Sandy says wearily.

It is wholly unsubtle, but it is still “Girls” at its best, at once affectionate and credible and lightly parodic. There is Hannah: impulsive, oblivious, tangled up in her own sloppy self-justifications. And then there is Lena Dunham, the wary third eye hovering above the action. “The joke’s on you because you know what? I never thought about the fact that you were black once,” Hannah tells Sandy. “I don’t live in a world where there are divisions like this,” she says. His simple reply: “You do.”

And I find myself back at the same place I was when Maya and I talked about Beyonce. No, Dunham’s attempt to introduce racial discourse into her show doesn’t suddenly make it diverse, but I think she still deserves some credit. If it sounds like I’m saying: the white girl gets a pass for not painting an accurate portrait of Blackness because she doesn’t have lived context/experience, that’s exactly what I’m saying. Why do we expect “all or nothing” from anyone who dares to align themselves with a few feminist values, even if they don’t call themselves feminists? When will we begin the process of meeting people where they are?

And, as Samhita wrote on this topic, maybe we should spend less time “scrutinizing [Dunham’s] personal behavior instead of looking at the real problem—the lack of diverse representations of women in popular culture.” Do we need to see realistic representations of Black girlhood on television? Yes, that’s why we need more Black girls writing shows. *raises hand* Do we need examples of diversity in film? Yes, that’s why we need more people from diverse backgrounds writing them. Truthfully, I’d rather not leave that task up to a white girl with “no Black friends.”

|

| Lena Dunham, being all entitled and shit |

|

| “Eh, what are you gonna do?” –privileged White dudes everywhere, in response to rarely getting called out for their bullshit |