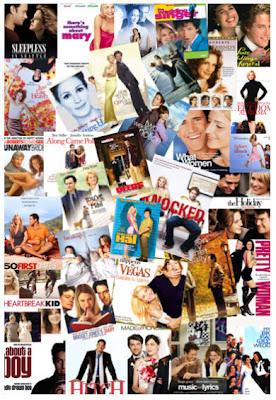

|

| some romantic comedies |

This guest post by Lady T previously appeared at her blog The Funny Feminist.

A few weeks ago, I announced my intention to tackle 52 romantic comedies over the course of one year. 2012 is the Year of the Romantic Comedy at my blog, and it shall henceforth be dubbed “The Rom-Com Project.” The Rom-Com Project is a completely serious endeavor, a social experiment, and in no way a cynical ploy to get a book deal by writing about

a year of doing something. In my post where I first announced the project, I explained my reasons for focusing on the romantic comedy:

I also think that looking at romantic comedies is a worthwhile feminist project. I want to look at how men and women are represented in these films. I want to look at the way romantic expectations are presented in our popular culture. I want to look at issues of consent. I want to look at the way the comedy genre affects the romance genre and vice-versa.

Readers responded well to this post and left me more suggestions than I needed, to the point where I have to decide whether to narrow down the list to 52, or expand the project to “100 Rom-Coms in a Year.”

But why focus on romantic comedies (one might ask)? Why not focus on comedies that happen to feature women?

Well, just for a lark, I looked at the

Wikipedia entry on “comedy film” and took note of the different sub-genres listed under the comedy banner, as well as the examples that were mentioned for each genre.

For the

fish-out-of-water genre, the entry lists six examples. 0 of 6 of these examples have female protagonists.

For the parody or spoof film genre, the entry lists three examples. 0 of 3 of these examples have female protagonists.

For the anarchic comedy film genre, the entry lists two examples. 0 of 2 of these examples have female protagonists.

For the black comedy film genre, the entry lists fourteen examples. 1 of these 14 examples (Heathers) has a female protagonist without a male co-protagonist, and fewer than half have a female co-protagonist.

I think you can all start to see the pattern here, but let me continue just to belabor the point.

Gross-out films. 4 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Action comedy films. 9 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Comedy horror films. 9 examples, 1 female protagonist (in Scary Movie).

Fantasy comedy films. 6 examples, 2 female co-protagonists (The Princess Bride, Being John Malkovich), 0 female protagonists without male co-protagonists.

Black comedy films. 3 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Sci-fi comedy films. 8 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Military comedy films. 9 examples, 1 female protagonist (Private Benjamin).

Stoner films. 4 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Some might argue with me on particular examples, but it’s obvious that dominant characters in comedy films are overwhelmingly male. (I also understand that Wikipedia is not an entirely accurate source of information, but the examples that are used to represent these different genres explains a lot about our cultural attitudes.)

But what about the romantic comedy?

If you look at the entry on romantic comedies, you see many more films that have female protagonists, or at least female co-protagonists. Especially significant is the list of top-grossing romantic comedies. 22 films are listed. More than half of them have female co-protagonists, some have one female protagonist, and one has (gasp!) more than one female protagonist (Sex and the City).

The romantic comedy genre gets a lot of flak. It’s considered a genre that’s more “shallow” than drama, but not funny enough to be a “real” comedy. Is it any coincidence that the romantic comedy is one of the few film genres, and possibly the only film genre, that regularly features women?

To me, the romantic comedy genre is an example of the struggles women face both as entertainers and as consumers of entertainment.

Love stories are dismissed as “girl stuff” (as though something aimed at women is automatically less than something aimed at men). A male-centric romantic comedy like Knocked Up is something with “mass appeal” when a female-centric romantic comedy like My Best Friend’s Wedding is “girl stuff.” Judd Apatow makes the same type of movie over and over again and gets praised despite the striking similarity in many of his films (down to style, story, and casting), but reviewers of What’s Your Number? can’t resist comparing the movie unfavorably to Bridesmaids, even though “a female protagonist” is almost the only thing those two movies have in common.

It’s a double-edged sword. Romantic comedies are looked upon with scorn, as fluffy and unimportant compared to dramatic films, but also not “edgy” or irreverent enough to be “real” comedies. But if a woman wants to watch a movie that is both a) funny and b) featuring a female main character, she doesn’t have many options available to her.

Sexism is deeply ingrained in our culture. Just look at my last paragraph. I typed the last sentence of that paragraph saying that “if a woman wants to watch a movie…with a female main character…” Then I looked back and realized that I, who tries to make a point of combating stereotypes and gender essentialism, automatically assumed that ONLY women would ever want to watch a movie with a female protagonist. That a man wouldn’t seek out or enjoy a movie with a female protagonist. That a man wouldn’t think a movie with a female protagonist was funny.

I have several problems with the romantic comedy genre. I dislike that women are almost always presented as people who are obsessed with fashion and shopping and shoes. (Not that there’s anything wrong with being obsessed with fashion and shopping and shoes – I would buy Zooey Deschanel’s entire wardrobe if I had the means. I’m only pointing out that we don’t see many female protagonists in rom-coms who are

not obsessed with fashion and shopping and shoes, and I would like to see a wider variety of characters.) I dislike that funny women are usually “pretty women in high heels who adorably fall down.” I dislike that women in romantic comedies are almost always teachers and cupcake bakers or art gallery owners or trying to make it in the publishing industry. (Again, not that there’s anything wrong with those careers – I just want more variety.) Or, alternately, these women are high-powered career types whose journeys revolve around letting free-spirited men teach them how to loosen up. (For more of these romantic comedy cliches, read Mindy Kaling’s

Flick Chicks, and then pick up

Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? And Other Concerns. I just finished reading it, and it’s hilarious.)

And yet, despite all of these cliches and stereotypes in romantic comedy films, I still want to spend a year analyzing the genre. I think it’s a worthwhile project because I want to examine our culture’s expectations about men and women and gender and sex and romance, and how romantic comedies play into (or don’t play into) rape culture. I am looking forward to this project.

But I’m not going to a lie. I’m a little annoyed and bitter that, if I wanted to spend a year writing about black comedies starring women, or parodies starring women, or any other comedy genre starring women, I would probably not to be able to come up with a list of 52 movies for any of those genres unless I reviewed a slew of obscure films that most readers wouldn’t recognize.

Final note: Whenever a woman (or a person of color, or disabled person, or gay person, or a person belonging to any marginalized group) writes a piece criticizing the lack of representation in media, it’s only a matter of time before a troll makes a comment along the lines of, “Well, if you think there should be more movies starring [this group], why don’t you write one yourself?” To that, I say, “All in due time. Alllll in due time.” I’m not writing about my super awesome women-centric movie ideas here just yet because I don’t want anyone to steal them. *shifts eyes, holds screenplay closer to chest*

—-

Lady T writes about feminism, comedy, media, and literature at the blog The Funny Feminist. Her essay “My Mom, the Reader” has also been featured at SMITH Magazine. A graduate of Hofstra University, she writes fiction about vampires, superhero girlfriends, and feisty princesses, and hopes to one day get paid for it. She contributed a review of Easy A to Bitch Flicks

.