Written by Brigit McCone.

From the Bitch Flicks that brought you “Birdman Is Black Swan For Boys” and “Fight Club Is Pride And Prejudice For Boys,” comes the thrilling conclusion of our Filmic Forced Feminization Trilogy: “Trainspotting is Pretty Woman For Boys”! No, really.

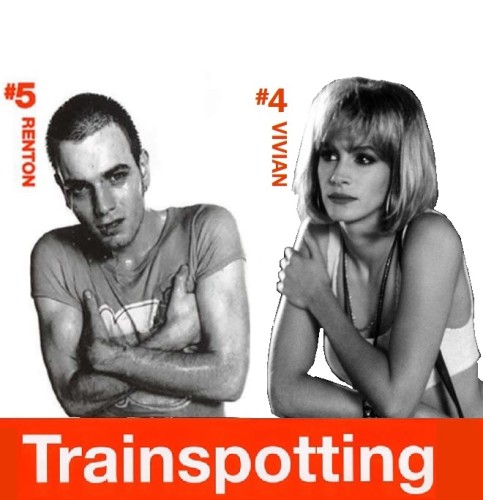

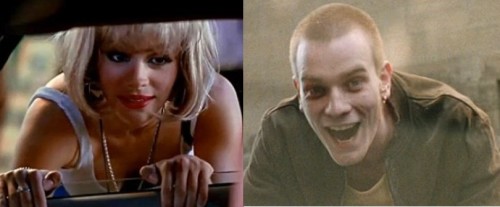

Consider the openings: Renton runs down the road to the voiceover of the iconic “choose life” monologue, before colliding with a car. The camera shares the perspective of the car’s occupants, stalled in their protective shell of metal, as this threatening creature of countercultural anarchy peers in at them. And laughs. Now consider our camera sharing Richard Gere’s perspective, stalled in the protective shell of his luxury vehicle, as the threatening prostitute of countercultural anarchy peers in at him. And laughs.

Vivian is an antidote to the stale marital maneuverings of mainstream culture. She flaunts her lack of pantyhose to scandalized elderly couples. She tells matchmaking materialists that she’s simply using Edward for sex. She regards the hypocrisy of mainstream respectability politics with undisguised contempt. Our assumptions about the inferiority of a prostitute’s life choices are challenged by the defiant anthem that plays as she struts: “things you only dream about, wild women do.” Just as Trainspotting dignifies its hero’s autonomy by openly acknowledging the attraction of heroin and the logic of his choice, so Pretty Woman openly acknowledges the attraction of sex work as social rebellion, financial autonomy and independence. Vivian might as well have her own monologue about the pressure to “choose wife.” Why would she want to do a thing like that?

Of course, the film ends with Vivian choosing wife, just as Renton finally chooses life, but they choose it on their terms. I’ve written before about how the supposed antifeminism of “whores” and “white knights” has blinded us to the politics of autonomy in Pretty Woman. Scratch its candy-coated surface, or scratch the edgily aggressive snarl of Trainspotting, and you reveal a shared approach to the challenges of stigma raised by prostitution and drug addiction. Such as…

The Failure Of Paternalism

The remarkable results that Portugal has achieved by decriminalizing drug use and treating addiction as sickness rather than crime, mirror the impressive achievements of New Zealand’s decriminalizing of sex work. Our urge to discipline and punish individual choice has been ineffective in preventing “vice,” sustaining organized crime and social inequality in the process. Trainspotting and Pretty Woman reflect this reality. Renton’s initial decision to come off drugs is presented as a spontaneous choice from his inner resolve. Later, his parents attempt to enforce a cure by locking him in his bedroom to go cold turkey. The legal system attempts to enforce a cure through the courts. Neither of these paternalist pressures are shown to be effective. Similarly, Vivian consistently refuses Edward’s attempts to treat her as an object of pity or a mistress, preferring the independence of sex work to the subordination demanded by paternalist savior narratives. Only by admitting his own need to be rescued, and offering full romantic equality on Vivian’s terms, can Edward persuade her to mainstream.

More than ineffective, each film presents social stigma as actively counterproductive. It is while independently trying to come off heroin, without medical support, that Renton must make his iconic dive into the crap-filled Worst Toilet In Scotland for his suppositories. It is when trying to mainstream that he becomes mentally vulnerable to the condescending pity and judgmental attitudes of others, driving his relapse. Likewise, it is when attempting to mainstream that Vivian must endure the metaphorical crap of the Worst Boutique On Rodeo Drive and it is while passing as respectable that she becomes mentally vulnerable to the humiliating judgments of Stuckey, where a prostitute’s uniform would make her feel defiantly “prepared.” Both Trainspotting and Pretty Woman argue that social stigma fuels defiance and deters mainstreaming. Though each film freely acknowledges the hazards of the lifestyle portrayed, from Pretty Woman‘s dead hooker in a dumpster and assault by Stuckey, to Trainspotting‘s dead baby and AIDS casualties, they remain firmly opposed to the hypocritical righteousness of dominant culture. Witness their choice of Begbie and Stuckey to represent mainstream ideology.

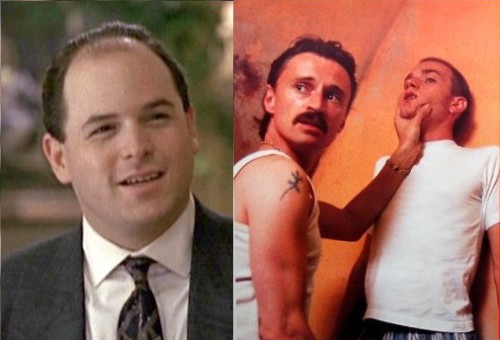

Begbie and Stuckey: Dominant Hypocrites

Phil Stuckey is a cunt, in the utterly unreclaimed, gender-neutral, Scottish sense of that word. He is a man who will eagerly solicit prostitutes, yet defend his right to hit them with a superior snarl of “she’s a whore!” In this, he mirrors Trainspotting‘s Begbie, who is content to profit from drug deals while righteously sneering over an addict’s choice to “poison their body with that shite.” Both Begbie and Stuckey have a toxic combination of arrogance and insecurity, a continual need to prove their status at the expense of others. The suppressed violence in Stuckey’s craving for the corporate “kill” erupts in his assault on Vivian, after being denied financial satisfaction. Begbie is chronically violent, craving the adrenalin of a brawl as much as addicts crave their drug of choice. In short, in remarkably similar ways, Begbie and Stuckey are deeply unpleasant cunts. It is into the mouths of these cunts that each film places the judgments of dominant society. Begbie expresses dominant opinions about drug addicts and trans* women. Stuckey expresses dominant opinions about sex workers. Both are depicted as dominant, domineering, and thriving.

Trainspotting and Pretty Woman choose to use the repulsiveness of Begbie/Stuckey as the spur that finally decides Renton/Vivian on mainstreaming. A classic savior narrative would use a righteous role model to represent the attraction of mainstream values; Trainspotting and Pretty Woman instead use the nauseous vileness of their representatives as catalyst. As an addict, Renton is forced to fill the pockets of the world’s Begbies. As a prostitute, Vivian is forced to service the ego of the world’s Stuckeys. By presenting mainstreaming itself as an act of resistance to mainstream exploitation, both films are able to realistically acknowledge its health and safety benefits without sacrificing their raised middle finger to mainstream righteousness. They resist the narrative of the mainstream’s moral superiority, not only through the repulsively mainstream Begbie and Stuckey, but through the lovable, marginalized Spud and Kit.

Spud and Kit: Performance Anxiety

The triumphant Renton is separated from Spud, and the triumphant Vivian is separated from Kit, not by their moral superiority but by their superior ability to perform socially. In Trainspotting‘s court scene, Renton effortlessly convinces as a clean-cut “pretty addict” (the kind you’d like to meet) as he plausibly swears “with God’s help, I shall conquer this terrible affliction,” avoiding jail. By contrast, Spud is nervous and inarticulate. He lacks Renton’s presentation skills and faces jail as a result. Kit suffers similar anxiety. Where Vivian effortlessly adapts to luxury clothes, Kit is afraid to hug Vivian in case she wrinkles her. She seems defensive in Edward’s hotel, taunting the clientele. Kit could not fake the respectability and “class” required from Edward’s escort. By pairing Renton with Spud, and Vivian with Kit, both films expose the nature of respectability as essentially hypocritical performance.

Admirably, neither Spud nor Kit ever punish their friends for their success. Spud allows Renton to steal the group’s drug money, knowing that Renton will be harshly punished if the alarm is raised. Kit appears genuinely delighted at Vivian’s good fortune for meeting Edward, and roots for her to find lasting happiness with him. In many ways, both Spud and Kit are morally superior to the protagonists. This moral worth is recognized and rewarded financially by both heroes: Vivian gives Kit a share of Edward’s payment and Renton leaves Spud a share of the drug money. Will Kit be able to become a Renton of recovered addiction and a Vivian of romantic success? Will Spud? We are only able to root for Kit and Spud’s success because Trainspotting and Pretty Woman present a world in which doom is not inevitable and good fortune is possible.

Inevitability vs. Agency

It is fundamentally dehumanizing to suggest that a group in society is inevitably doomed. We know that our own lives are at the mercy of luck and chance; our rewards and punishments are uneven and not proportional to what we deserve, if deserving can even be measured. We make choices, from moment to moment, and we struggle for our own happiness as best we can. To deny someone that choice, that chance and that struggle is to deny our identification with them, as well as any possible support of them. If their doom is inevitable, none of us can be held responsible for failing to prevent it, or even for causing it. Which helps to explain the disposable hookers of Grand Theft Auto.

Renton’s doom is not inevitable. He stood the same chance of contracting AIDS as his fellow addicts; some were lucky, others were not. Likewise, a prostitute who climbs into the car of a slick, suited yuppy could be finding love and fortune with Pretty Woman‘s Edward, or facing gruesome death at the hands of American Psycho‘s Patrick Bateman. The difference is in film genre, not life choice. Here’s an interesting point: have you ever heard anyone point out that Trainspotting depicts heroin use as the direct result of hetero-male sexual failure? Renton and Spud are both shown relapsing after humiliating failures in their attempts to connect with women. Tommy turns to heroin after a bad break-up. Yet, somehow, no causal relationship is assumed between a man’s sex life and his choices. So, why is it so impossible to imagine a prostitute as a survivor of sexual abuse, without the dehumanizing implication that this has mindlessly predetermined her choice to do sex work? Trainspotting‘s Sick Boy and Renton are equally allowed to be haunted by their failures in childcare, and Renton to hallucinate an accusing baby, without being judged “babycrazy” as Ally McBeal. Why is Vivian a “tart with a heart,” yet Renton can show scruples over underage sex and give cash gifts to Spud without being a “magic addict”?

Though Hollywood no longer has a Hays Code demanding punishment for characters who break the law, films still enforce that convention for both sexes. Stuckey’s devastating corporate “kills” are socially acceptable; Vivian’s provision of sex acts for a mutually agreed fee is not. Therefore, it is Vivian that we are conditioned to expect to see suffering consequences, until Pretty Woman flips that script. According to cinematic convention, stealing a bag of drug money should be the beginning of a No Country For Old Men-style thriller of inevitable doom. In Trainspotting, it is the hero’s happy ending. By offering its heroin addict a chance to evade all consequences for his actions, and to claim the prosperity and respectability that is supposedly the social reward for virtue, the film calls our bluff. If we truly pity the tragic fate of society’s doomed victims, we should rejoice in Renton’s lucky escape. However, as Oscar Wilde puts it: “anyone can sympathize with the sufferings of a friend, but it takes a very fine nature to sympathize with a friend’s success.” Spud and Kit might have that very fine nature, but do we? Mark Renton has no time for your puritanical need to see him punished for his life choices. Renton is going to blend in with the mainstream and become indistinguishable from all the other hypocrites. Renton was born slippy, and he’s going to get away with it. Because Renton has secretly been Cinder-fuckin-rella all along.

What more proof do you need that Trainspotting is Pretty Woman for boys?

Brigit McCone always thought Vivian should have chosen Barney the hotel manager, but recognizes he’s probably married. She writes and directs short films and radio dramas. Her hobbies include doodling and irritating Fight Club fanboys.