Written by Robin Hitchcock

|

| Film critic Roger Ebert, 1942–2013 |

The radical notion that women like good movies

Written by Robin Hitchcock

|

| Film critic Roger Ebert, 1942–2013 |

|

| Clueless movie poster |

|

| Dionne and Cher |

|

| Cher and Tai make up after a fight |

| BF co-founders Steph and Amber at the 2010 Athena Film Festival |

Written by Robin Hitchcock.

|

| The Journey of Natty Gann |

When I was a young girl, I was obsessed with the trailer for The Journey of Natty Gann (for which I will issue a spoiler warning, although I find it dubious that a Disney family film could be spoiled):

|

| John Cusack as Harry |

|

| Natty Gann (Meredith Salenger) gets her Katniss on |

Written by Robin Hitchcock.

|

| The Journey of Natty Gann |

When I was a young girl, I was obsessed with the trailer for The Journey of Natty Gann (for which I will issue a spoiler warning, although I find it dubious that a Disney family film could be spoiled):

|

| John Cusack as Harry |

|

| Natty Gann (Meredith Salenger) gets her Katniss on |

|

| Eve’s Bayou dvd cover |

|

| Jurnee Smollett as Eve in Eve’s Bayou |

|

| Rodriguez, the central figure of documentary Searching for Sugar Man |

He replied that he had known of the artist, but only because he used to work in broadcasting. This short and interesting answer was essentially all I asked for; a black South African commenting on the fact that Rodriguez was virtually unknown or seemed to not have played a vital role in the lives of black South Africans. Not to prove that Rodriguez did not matter, but to acknowledge that though Rodriguez fan base was mainly white, it does not mean that black South Africans have nothing to contribute with in this particular and fascinating aspect of South Africa during apartheid. A story about Rodriguez would be incomplete without the mentioning of apartheid, and a story that talks about apartheid without including a black South African experience feels incomplete to me.

|

| South Africans protesting apartheid in the Soweto uprising of 1976. |

|

| Michael Caine, Angelina Jolie, Hilary Swank, and Kevin Spacey at the Academy Awards in 2000 |

.png) |

| Scatter plot of ages of Oscar winners in acting categories

I apologize for the hokey pink and blue color scheme, but it’s the easiest way to illustrate that the cluster of women winners in the acting categories falls a bit below that of the men. This plot also makes it clear that there have been no major trends over the years; the winners aren’t generally getting any older or younger in any category.

The average age of the Best Actress winners is 36.2 with a standard deviation of 11.67; and the average age of Best Actor winners is 43.9 with a standard deviation of 8.86. Best Supporting Actress’ ages average at 39.9 with a standard deviation of 13.86; Best Supporting Actors’ ages average at 49.6 with a standard deviation of 14.44. Here’s how these distributions overlap:

In the supporting categories, we see a wider distribution of the ages of the winners, not only because children and the elderly are more often in supporting roles, but because child actors are often placed in the supporting category even when they play lead roles (e.g. Timothy Hutton, Tatum O’Neal, Patty Duke). [This year, of course, breaks from that pattern, with both the oldest-ever and youngest-ever nominees in the Best Actress category (Emmanuelle Riva, age 85, and Quevnzhané Wallis, age 9).]

I ran an ANOVA (analysis of variance) test and Tukey’s multiple comparison post-test and found that nearly all the groups’ distributions vary to the point of statistical significance. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is no statistical significance between the distribution of ages in the lead and supporting acting categories for women (but the difference between ages of lead actors and supporting actors is significant). Interestingly, there’s also no statistical significance between Best Supporting Actress winners’ ages and Best Actor winner’s ages.

So I also lumped the best lead and best supporting categories together by sex and ran a t-test to get more a more simple answer. This test yielded a p<.0001, indicating extreme statistical significance.

Now that we know this data is statistically significant, let’s try to visualize it more clearly:

First I broke the groups down demographically:

As you can see here, more than half of Best Actress winners (62.35%) are age 35 or younger, whereas only 14.12% of Best Actor winners are that young. Male actors younger than 35 are also rarely awarded in the supporting category (14.48%), but women under 35 still make up nearly half the winners of Best Supporting Actress (47.37%).

I also broke down the winners’ ages by decade:

This chart further illustrates what we already know: the supporting categories are open to a wider range of actors of either sex, but the female categories are dominated by younger performers, whereas the male categories skew older. Like with my analysis of Best Picture nominations versus lead acting nominations, I don’t think this is as much of a problem with the Academy as it is with Hollywood itself. If there were more strong roles for older women (and perhaps more strong roles for younger men?) the age distribution of Academy Award winners for acting would be more aligned between the sexes.

Perhaps the most striking figure I found is that there has been only one winner of Best Actor under the age of 30 (Adrien Brody, who won at age 29 for The Pianist in 2003) but twenty-nine Best Actress winners in their 20s.

As a final note, I’ve been asked, as an Oscar-obsessed feminist, if there is any reason why the acting categories should be split by sex. I’ve never had a good answer, mostly because it opens up a whole kettle of cats about the rejecting the gender binary and biological essentialism while celebrating gender differences that I generally don’t have the time or interest to drag into my awards talk. But reviewing all this data and seeing the reflection of various types of sex discrimination within it, I think the Academy isn’t ready for a gender-neutral “Best Performance” award.

|

|

Written by Robin Hitchcock

|

| Last year’s Best Actress and Best Actor Oscar winners, Meryl Streep and Jean Dujardin. The Iron Lady was not nominated for Best Picture. The Artist was nominated for and won Best Picture. |

|

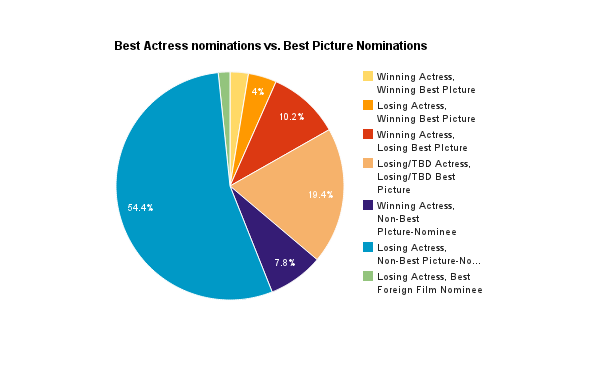

| Pie chart illustrating relationship between Best Actress nominations and Best Picture nominations |

|

| Pie Chart illustrating relationship between Best Actor nominations and Best Picture nominations |

|

| 2003 Best Actor winner Sean Penn (for Best Picture-nominated Mystic River) with 2003 Best Actress winner Charlize Theron (for non-nominated Monster). |

.png) |

| Charts showing disparity between Best Actor/Actress and Best Picture nominations over years and decades |

|

| The male cast of Beautiful Girls |

It always raises a red flag for me when a film presents men one way and women another. My feminist knee starts to jerk—GENDER BINARY—BIOLOGICAL ESSENTIALISM—DANGER WILHELMINA ROBINSON!

So 1996’s Beautiful Girls, an ensemble belated-coming-of-age story centered around New York City pianist Willie (Timothy Hutton) returning to his hometown for a high school reunion, starts out on notice because it centers on big ideas about The Way Men Are. And that’s before it goes down an even more troubling Lolita-esque road. And yet, it’s one of my favorite movies. I’m just not sure if I should qualify it as a guilty pleasure.

A beautiful girl can make you dizzy, like you’ve been drinking Jack and Coke all morning. She can make you feel high full of the single greatest commodity known to man – promise. Promise of a better day. Promise of a greater hope. Promise of a new tomorrow. This particular aura can be found in the gait of a beautiful girl. In her smile, in her soul, the way she makes every rotten little thing about life seem like it’s going to be okay.

|

| Rosie O’Donnell as Gina in Beautiful Girls |

|

| Timothy Hutton and Natalie Portman in Beautiful Girls |

But before I go any further with giving Beautiful Girls the benefit of the doubt, I should mention that the core plot thread is the main character Willie falling in love with the girl next door. The girl next door who is thirteen-years-old. RECORD SCRATCH! This thirteen-year-old neighbor, Marty (Natalie Portman), is so charming and vibrant and precocious (she explains that she has an “old soul”) that it is easy to sympathize with Willie’s creepy crush. And it helps that Willie, most of the time, knows that his feelings for Marty are skeevy and wrong. [When I first saw Beautiful Girls, I was fourteen, and had already had my share of crushes on age-inappropriate men, so I related to Marty’s impossible longing more than I worried about the inappropriateness of Willie’s. My husband watched this movie for the first time this week, at age 29 (the same age as the character Willie), and could not get past the ick factor of someone his age pining for a girl that young. So your mileage may vary regarding the possible automatic disqualification of Beautiful Girls.]

|

| Uma Thurman as Andera in Beautiful Girls |

|

| Lauren Holly as Darian and Matt Dillon as Tommy in Beautiful Girls |

| Jodie Foster at last year’s Golden Globes |

Written by Robin Hitchcock.

This weekend at the Golden Globes, Jodie Foster will be honored with the Cecil B. DeMille Award to honor her lifetime achievement in cinema. At age 50, Jodie Foster is the fourth-youngest recipient of the award, but having started acting at only three years old, her career spans as long as many more senior actors, directors, and producers.

| Foster’s priceless response to Ricky Gervais’ jokes about her sexuality at last year’s Globes |

And there can be no doubt this has made a direct contribution to Foster’s ability to practice her craft; the piece she authored for The Daily Beast responding to the tabloid spectacle surrounding (her Panic Room co-star) Kristen Stewart’s affair with director Rupert Sanders asserts, “if I were a young actor today I would quit before I started. If I had to grow up in this media culture, I don’t think I could survive it emotionally.” Foster elaborates:

Acting is all about communicating vulnerability, allowing the truth inside yourself to shine through regardless of whether it looks foolish or shameful. To open and give yourself completely. It is an act of freedom, love, connection. Actors long to be known in the deepest way for their subtleties of character, for their imperfections, their complexities, their instincts, their willingness to fall. The more fearless you are, the more truthful the performance. How can you do that if you know you will be personally judged, skewered, betrayed?

Jodie Foster has built her career on her ability to communicate vulnerability without diminishing her dignity, a compelling balance she is able to bring to her characters partially because her talent is not eclipsed by her celebrity.

| Jodie Foster in The Accused |

A recurring thread in Foster’s films is the issue of credibility: her characters often have to fight to have their voices heard and stories believed, and/or to be afforded the authority and status that they rightfully deserve. In The Accused, the first film for which Jodie Foster won a Golden Globe and an Academy Award for Best Actress, Foster plays Sarah Tobias, a victim of a brutal gang rape. The prosecuting attorney Kathryn Murphy (Kelly McGillis) makes a plea bargain deal with the perpetrators in part because she thinks Sarah makes a poor witness for a trial because she has a reputation for promiscuity and uses drugs and alcohol. Sarah has to continually reassert that she is worthy of justice and deserving of being heard, even to her ally Murphy. Ultimately, Sarah is given the platform to tell her story in the court and help secure some measure of justice toward those who assaulted her.

|

| Jodie Foster as Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs |

Clarice Starling in Silence of the Lambs, perhaps Foster’s most celebrated role, is largely defined by her ability to command respect from a world that seems hell-bent on denying her equal status (as is astutely analyzed in this post by Jeff Vordham that previously appeared on Bitch Flicks.) Hannibal Lecter at first dismisses Clarice as a “rube,” but she wins his respect by forthrightly communicating with him through his constant attempts to play status games with her.

Like Clarice Starling, Ellie Arroway, Jodie Foster’s character in Contact, is not taken as seriously by her peers and colleagues despite her merit. Arroway has to passionately fight to keep funding for her search for extraterrestrial communications. Even after the value of her research is proven by her discovery of a message from outer space, she is kept on the periphery of the (largely white and male) “in-crowd” that responds to this development. In the film’s final act, Arroway’s experience travelling through a wormhole and speaking with a representative of the alien species who sent the message is officially disavowed due to lack of evidence, although it is clear most of the characters trust the veracity of her account. Again, Jodie Foster’s gift for credibility connects the audience to her character’s struggle to be accepted and believed.

| Jodie Foster fights to be believed in Flightplan |

This recurring theme of asserting one’s credibility and value in the face of denial and dismissal is a fundamentally feminist motif. When she appeared on Inside the Actors Studio, Jodie Foster discussed her role in Flightplan, which also hinges on her character’s questioned credibility. The character was originally written for a man to play, and when Foster lobbied for the role she specifically noted that this conflict is inherently female: “‘There’s a point in the film where she is so bereft that she has to consider that she’s lost her mind… Well that’s a scene a man could never play. A man in a crisis like this wouldn’t question his sanity, he’d question someone else’s.”

Jodie Foster understands that as women, each of her character’s credibility is considered inherently questionable by a sexist society. In film after film, Foster infuses her characters with an authority that silences those doubts. And as such, watching Jodie Foster’s characters is often immensely satisfying to the feminist viewer. It’s fantastic to see the Hollywood Foreign Press honor her remarkable career with the Cecil B. DeMille award. Congratulations, Jodie.

|

| Kirsten Dunst, Isla Fisher, and Lizzy Caplan in Bachelorette |

|

| Rebel Wilson as the bride, a well-adjusted foil for the main characters |

|

| Bachelorette has a happy ending without absolving the characters |