|

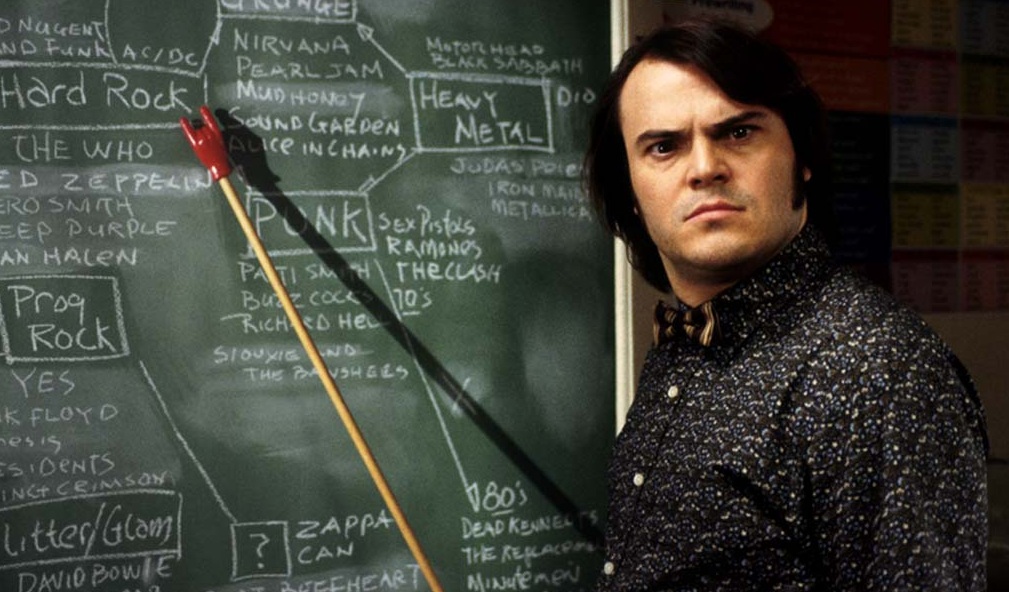

| Jack Black in School of Rock |

The first decade of this millennium was a pretty good time for American culture, all in all, George W. Bush notwithstanding. YouTube was invented, the pound symbol was saved from oblivion by hashtags, and Tina Fey got famous.

But the early-to-mid aughts also brought something really unpleasant to our culture, something that had been brewing since the dawn of Generation X: the celebration of The Man Child. In everything from Old School to Role Models to the Complete Works of Judd Apatow, male characters Peter Pan’d their way through life, even as pesky forces like bills and harping girlfriends tried to harsh their mellow.

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the Man Child trope from a feminist point of view is his female counterpoint: the Nagging Killjoy Shrew. This woman tells the Man Child to grow up, to accept responsibility, to stop acting exactly like he did when he was 19. To which the Man Child responds, “stop crushing my soul and my dreams! I just gotta be me.”

I have no idea where the cultural idea that women are better at being grown-ups than men came from. I think it may have been some misguided attempt to correct previous sexism while simultaneously getting out of having to do the dishes. I’m also not sure how the patiently suffering Sitcom Wife of the Man Child so prevalent in the 80’s and 90’s turned into the Hellish Shrewbeast of the 2000’s Aptovian comedy.

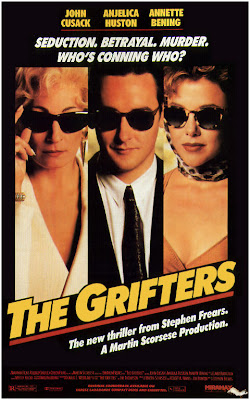

School of Rock, the 2003 film written by Mike White and directed by Richard Linklater, typifies the Man Child vs. Shrewbeast dynamic, which is a shame, because it is otherwise an extremely entertaining and lovable film, and I wish I could recommend it without reservation.

Jack Black plays Dewey Finn, a man-child whose unyielding pursuit of a rock n roll stardom has thwarted his maturation and upward mobility toward certain signifiers of adulthood like having an actual bed in an actual bedroom instead of a mattress on the floor of your buddy’s living room. Dewey’s roommate Ned Schneebly (Mike White) has given up the rock and roll dreams he shared with Dewey in his younger days for the more stable and adult life of a substitute teacher. Dewey assumes Ned’s identity, taking a substitute teaching job at an elite prep school in order to make rent, with the side bonus of recruiting a bunch of children into his new rock band. Events occur, life lessons are learned by all, young selves are actualized by the transformative power of music, and humble offerings are made to the gods or rock. Like so many stunted artists, Dewey and Ned discover that teaching their craft to the next generation of dreamers allows them to stay active with their passion while earning a respectable living doing it. Roll adorable credits with the kids’ band playing an AC/DC song.

|

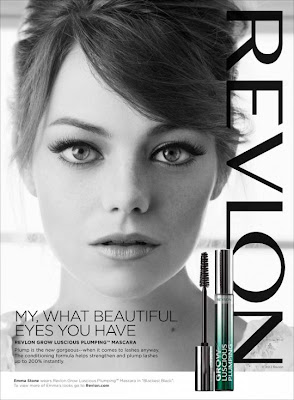

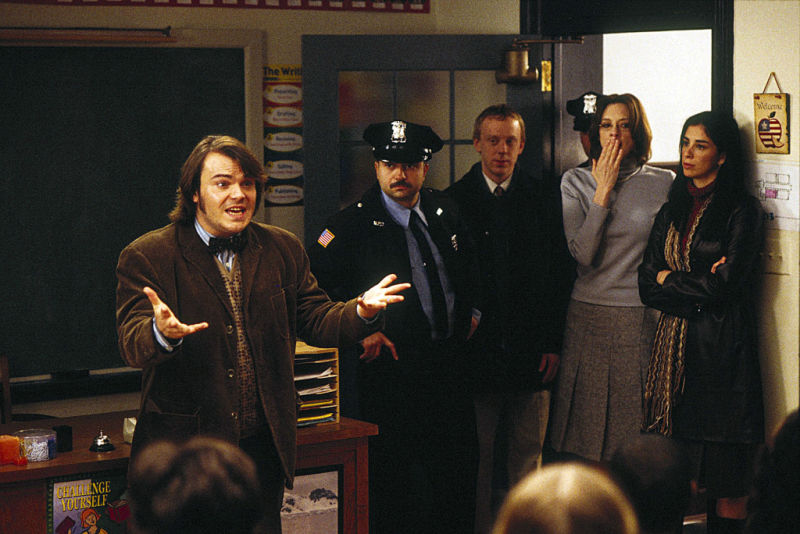

| Dewey vs. The Man, including a cop, the man whose identity he stole, his employer, and Patty |

But along the way, Dewey (and Ned) conflict with various Hellish Shrewbeasts. First, Ned’s girlfriend, Patty (Sarah Silverman), who instigates Dewey’s deception by insisting he GASP, actually pay rent to continue staying in her boyfriend’s apartment (that bitch.) I cannot for the life of me figure out why Sarah Silverman accepted this role. Every word out of Patty’s mouth comes out sounding like a verbal a punch in the face (to Dewey) or yank on the leash (to Ned). She’s one of the most unpleasant characters I’ve ever seen on screen, indisputably the villain of the piece, even though her attitudes (Dewey should get a job so her boyfriend doesn’t have a Man Child living on his living room floor anymore; Dewey should not be casually forgiven for fraud and child endangerment) are entirely reasonable. I don’t know if Silverman was miscast and/or misdirected, but her caustic performance unfortunately bolsters the Man-Child-Good/Responsible-Adult-Woman-Bad dynamic in School of Rock. Silverman is fantastic at playing the elusive female variant of the Man Child [see also Dee Reynolds in It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia (after the pilot, where her character is a much more pedestrian voice of reason), and Daisy Steiner in Spaced] so she might have exaggerated the shrewish aspects of her character in an attempt to show range.

|

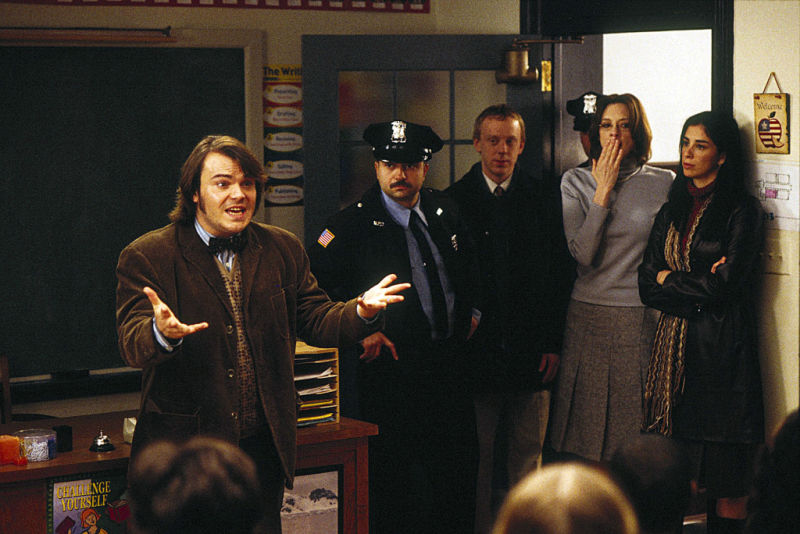

| Joan Cusack as Principal Mullins with Jack Black |

Patty isn’t the only flavor of Shrewish Nemesis Dewey must work around in School of Rock, and I’m not sure if that makes matters better or worse. Next up is the principle of the school Dewey has conned his way into, Rosalie Mullins (Joan Cusack). Ms. Mullins is a stickler for rules and discipline, but it is clear that her straight-laced authority is part of what makes her school so exceptional. While Ms. Mullins inspires fear in her students and isn’t exactly liked by her colleagues (which she laments), but she is undeniably respected, both by the characters (even Dewey!) and by the film itself. Unlike Patty, we see the lighter side of Ms. Mullins, first when Dewey discovers the key to loosening her up is a third of a beer and a Stevie Nicks jam on the jukebox, and later when she jubilantly congratulates her students after their climactic performance at the battle of the bands.

|

| Miranda Cosgrove as Summer Hathaway, class factotum and band manager. |

Finally, there is a mini-Shrew in the form of “Class Factotum” Summer (Miranda Cosgrove). Summer has learned to play the game at her elite school, racking up gold stars and grade grubbing her way to the top. She and Dewey butt heads at first, but Dewey quickly deduces he can manipulate Summer into going along with his antics by giving her a somewhat specious mantle of authority as Band Manager. The twist is that Summer takes on this role with aplomb and ends up being a vital part of the Band’s production team (her new interest leading her father to ask in one of the best lines of the movie, “Why has my daughter become obsessed with David Geffen?”). One of the many ways that School of Rock is exceptional is how much dignity it affords its well-rounded child characters, which makes it no surprise that young Summer is the most sympathetic of the Shrews.

It’s unfortunate that School of Rock relies so heavily on the Man Child vs. Shrewish Woman dynamic, because it is otherwise a funny, heartwarming, endlessly entertaining film. It’s a comfort food flick for me, something I put on to pull me out of a funk. I was almost mad at my feminist goggles for revealing this unfortunate pattern.

|

| “Write me a better reference!” |

One more quick feminist gripe before I go: I know the character speaking this line of dialogue is nine and wouldn’t necessarily know any better, but it is a CRIME that when drummer Freddie challenges Bassist Katie to name “two great chick drummers” she offers up Meg White before Moe Tucker or Gina Schock. A CRIME.