More Behind-the-Scenes Inequality in the Trek Series at Trekkie Feminist

What have you been reading/writing this week? Tell us in the comments!

The radical notion that women like good movies

More Behind-the-Scenes Inequality in the Trek Series at Trekkie Feminist

What have you been reading/writing this week? Tell us in the comments!

More Behind-the-Scenes Inequality in the Trek Series at Trekkie Feminist

What have you been reading/writing this week? Tell us in the comments!

|

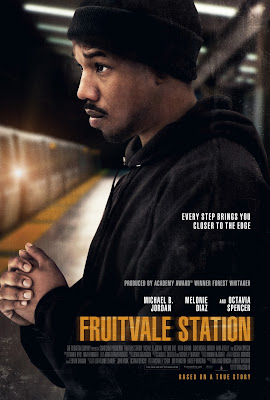

| Fruitvale Station movie poster. |

Written by Leigh Kolb

Fruitvale Station, unlike most feature films, is not told from and for the perspective of the white gaze. For white audiences, this is startling, uncomfortable and heartbreaking. It should be.

The film is a harrowing re-telling of the true story of Oscar Grant, who was killed by a police officer in the early morning hours of New Year’s Day 2009.

|

| Oscar Grant (Michael B. Jordan) and girlfriend Sophina (Melonie Diaz). |

“…black children in this country have never been safe. I think it’s really important that we remember the four little black girls killed in Birmingham and realize that’s where the type of white supremacist, terrorist assault began. That killing sent a message to black people that our children are not safe. I think we have to be careful not to act like this is some kind of new world that’s been created but that this is the world we already existed in.”

|

| Oscar’s mother (played by Octavia Spencer). |

“By the time the credits roll, Oscar Grant has become one of the rarest artifacts in American culture: a three-dimensional portrait of a young black male—a human being. Which raises the question: If Grant was a real person, what about all these other young black males rendered as cardboard cutouts by our merciless culture? What other humanity are we missing?”

“Oscar was always talking about getting a house and one of the reasons he wanted to get a house is because he’d have a backyard for the first time and he could own a dog… And he wanted a pit bull. That was the kind of dog that he likes … it’s interesting because when you hear about pit bulls in the media, what do you hear about? When you hear about them in the media, you hear about them doing horrible things. You never hear about a pit bull doing anything good in the media. And they have a stigma to them … and, in many ways, pit bulls are like young African-American males. Whenever you see us in the news, it’s for getting shot and killed or shooting and killing somebody — for being a stereotype. And that’s what you see for African-Americans in the media and the news.…So, there’s a commonality with us and pit bulls — often we die in the street. Do you know what I mean? That’s where we die.”

|

| There is a focus on Oscar’s relationship with his daughter, Tatiana (Ariana Neal). |

|

| The black men are profiled and taken off the train car (while the white man in the fight remains on the train), accused and arrested. Oscar is killed. |

“Some problems we share as women, some we do not. You fear your children will grow up to join the patriarchy and testify against you, we fear our children will be dragged from a car and shot down in the street, and you will turn your backs upon the reasons they are dying.”

|

| Timeline of real events. |

|

| Sandra Bullock and Melissa McCarthy in ‘The Heat’ |

Written by Megan Kearns.

I was extremely excited to see The Heat. Sandra Bullock and Melissa McCarthy, both of whom I love, headlining a comedy? As a huge fan of Bridesmaids, seeing self-proclaimed feminist Paul Feig direct another lady-centric comedy got me giddy with excitement. AND with Bullock and McCarthy??? Yes, please! I don’t care what anyone says, Sandra Bullock is a fantastic actor, even in shitty films. And McCarthy is hilarious.

|

| No, no, no, just no |

And there’s Mullins’ five-minute (supposedly humorous) tirade on the size of her boss’ balls. How his balls are little “girl balls.” That’s right, let’s insult a guy by insulting the size of his testicles. Only “real” men have balls. Wait no, only “real” men have big balls. Newsflash, masculinity isn’t tied to scrotum size. And trans men may not have balls at all. They’re still men.

Then of course there’s DEA Agent Craig, aka The Albino. Did anyone else cringe at this?? God I hope so. Albinism is a disability. So now we’re making fun of people with disabilities for “looking like evil henchmen” and calling them “Snowcone??” Make it stop.

With all the offensive “jokes,” I was expecting fat-shaming jokes too. I loved that Melissa McCarthy’s weight was never an issue in the film. No jokes were made about her weight. Oh wait, I take that back. DEA Agent Craig tells her she looks “like the Campbell soup kid all grown up.” Really? We see Mullins as a sexually confident, assertive woman and we can’t get away without some fat-shaming snark? There is however an epic take-down of the horrors and toxicity of beauty culture in the form of Spanx. Yes, I’ve worn them, yes they are a demonic torture device. This was especially awesome considering the hideously disgusting fat-shaming vitriol Rex Reed spewed at McCarthy.

|

| Screw you, Spanx! |

But I have to say that while part of me is delighted to see different depictions of gender presentation, particularly non-stereotypical depictions of beauty (not every woman wants to wear dresses and lots of make-up), does Melissa McCarthy always have to be in slovenly clothes or ridiculous costumes in every movie I see her in?? She’s a beautiful woman. But it’s as if the films she’s in don’t believe that a plus-size woman can be. Why can’t we see a plus-size woman looking different? Or for that matter, why can’t we see more women of all sizes on-screen??

I did love Bullock and McCarthy’s camaraderie and watching their friendship unfold. And it’s fantastic to see two women over the age of 40 headlining a blockbuster movie. Especially when Hollywood abhors aging women and suffers from massive amounts of ageism. And you could tell they had a fucking blast making this movie. It was also awesome to not have a romance in the film, an aspect that delighted Feig as well. While there were flirtations, no romance upstaged the film. The ladies’ sisterhood took center stage.

While there’s very little commentary on gender and sexism, and an ass load of misogyny spewed by DEA Agent Craig — Sidebar, is that why it’s okay to make fun of his disability, because he’s a douchebag?? No, no, no — Ashburn and Mullins kind of “blow off misogynistic bullshit.” But thankfully there’s a very brief and subtle commentary on sexism in the workplace amidst a conversation between Ashburn and Mullins at a bar about how hard it is to be a woman in this line of work.

But did it have to follow in the shadow of buddy-cop movies by also containing transphobic, ableist and racist jokes? Couldn’t it have done without that??

Sadly I wasn’t a huge fan of The Heat. I wish I had been. But I just couldn’t get past the extremely problematic humor. Sigh. I wish it hadn’t been so racist, ableist or transphobic. I wanted to like this, especially because it was written by Katie Dippold, a writer and producer of my fave feminist TV show Parks and Rec. But feminism isn’t just about gender equality and putting more women in film. Although that’s a huge start. It’s about combating all forms of institutional discrimination and oppression. And not perpetuating prejudice.

|

| If only ‘The Heat’ could have been as awesome as these ladies. |

Despite its flaws, I wholeheartedly believe we need more female-centric films. Way more. And you know what? I’d rather have a female-centric movie I’m not a big fan of rather than none at all.

I’ve read that author (and very funny tweeter) Jennifer Weiner doesn’t like to criticize or speak negatively about books by other female writers because she knows how difficult it is for women to get published. And then when they do, male authors get reviewed more often, and typically by male critics, since gender disparity exists in the critic world too.

And I totally get why she does this. Sisterhood and solidarity can be extremely powerful. There’s a dearth of female film directors, female-fronted films, female screenwriters, female film critics. So I always feel guilty when I don’t lavish a female-centric/penned/directed film. But here’s the thing. I really shouldn’t have to worry about whether or not my critique is going to derail other female filmmakers. Not that I’m saying my words carry as much weight as say NY Times’ Manohla Dargis or anything. But I don’t want to add to the din of voices hyper-scrutinizing women-led films.

Then I can critique a film to my heart’s content without worrying that some asshat in Hollywood thinks they shouldn’t greenlight more women-centric films. Hollywood never thinks to stop making movies with male protagonists. One shitty dude-centric movie? Bring on more dude films. A shitty women-centric movie?? All lady movies must suck.

For those of us who followed the girls on the hit HBO series, Sex and the City: The Movie, directed by Michael Patrick King, was a hotly anticipated film by the time it was released in 2008. We are familiar with Carrie as an avid writer, a New York fashionista, and an independent woman who consistently shies away from marriage. Certainly, Carrie’s disinterest in marriage throughout the show’s run can be interpreted as feminist by audiences. However, Carrie is quickly swept up in pre-matrimonial hysteria such as her designer dress and guest list. Big tells Carrie repeatedly throughout the film, “I want you,” as opposed to the desire for an extravagant wedding, but this sentiment seems to fall on deaf ears. The underlying message–and it’s a feminist one–seems to be this: smart girls don’t fall in love, smart girls love themselves. We meet Carrie as a woman who is attempting to negotiate these two philosophies, and by the end of the film, Carrie successfully marries Big but also prioritizes herself. In fact, her talk of marriage with Big originates from her drive for self-preservation. In reference to their swanky new apartment, she tells Big, “I want it to be…ours,” rather than his.

|

|

Carrie marks her territory at “Heaven on Fifth,” as she calls it.

|

“I wouldn’t mind being married to you. Would you mind being married to me?” Big casually questions as the pair prepare dinner. Carrie requests a “really big closet” in lieu of a diamond ring, a somewhat radical move that breaks with tradition as well as the stereotype that many women are “gold diggers” who equate a man’s commitment to the size of the rock he offers her. Rather, Carrie is financially equipped to find and purchase a diamond herself if she decides she’d like one. Carrie neither supports nor challenges the concept of marriage; throughout six seasons of Sex and the City on HBO, Carrie finds that marriage doesn’t suit her and she’d rather not play the role of wife. She tells Samantha, “There’s no cliché, romantic, kneeling on one knee, it’s just two grown-ups making a decision about spending their lives together.” However, Big does kneel down on one knee to formally propose inside “Heaven on Fifth’s” walk-in closet. In this space he builds, Big is “making room” for his bride, and this act of creation is at once romantic and understated. For Carrie, this gift is paramount in Big demonstrating his commitment to her, but hasn’t he already done so in a multitude of other ways?

|

| Contrary to Charlotte’s engagement party toast, Big remains grounded in reality as Carrie is the one “Carried away.” |

|

| Charlotte is a spokesperson for the joys and functionality of marriage within a heteronormative lifestyle, complete with the nuclear family by the film’s conclusion. |

|

| It’s not marriage that can “ruin everything,” but over-the-top weddings: rituals that become more significant than the love, support, and sacrifice they symbolize. |

Bringing the gang on her honeymoon is a decidedly feminist move on Carrie’s part; they are her support system and her surrogate lovers while she and Big are separated. Samantha even spoon-feeds her in bed as Carrie’s being “jilted” at the altar effectively infantilizes her while in Mexico. When audiences observe this pathetic and uncomfortable scene, we are confronted with the notion that, along with Miranda, Samantha has transformed into a maternal character while Carrie grieves. This is undoubtedly the closest Samantha will ever come to motherhood. “Will I ever laugh again?” Carrie asks, and of course, it’s when Charlotte shits her pants. The girls are a reliable source of Carrie’s happiness and stability, a reflection of who she is rather than who she wants to be. Unlike the second movie, in which the gang travels to Abu Dhabi, Samantha is more invested in her friend’s wellbeing than having sex with random men.

|

| Samantha happily mothers Carrie at her low point, and even winks at her as she stirs her food. |

When Carrie returns from Mexico, she takes on an assistant, and it becomes noticeable that Louise (Jennifer Hudson) is the only black character in the film, a surprising detail given that the setting is New York City. In fact, when searching for a new apartment with her son and nanny, Miranda excitedly says, “Look! White guy with a baby! Wherever he’s going, that’s where we need to be.” Is it me or is this line inextricably offensive? A white man carrying a child is highly symbolic of traditional heteronormative values. Together, these alarming observations render the film both racist and classist. Miranda’s in search of an upscale, and thus white, neighborhood that’s safe for her son.

|

| The poor colored girl from St. Louis is new to the luxury of owning as opposed to renting. |

On Halloween, Charlotte suggests to her adopted Chinese daughter, Lily, that she can be Mulan for Halloween, but Lily instead chooses to be Cinderella. Even at her young age, Lily embraces whiteness as a beauty ideal and is more stimulated by the glamour of ball gowns and being rescued by a handsome prince than battle armor and the spoils of war. Seemingly, the fantastical princess narrative trumps a feminist warrior’s tale, at least for a girl young enough to still believe in “happily ever after.”

|

| The laughably mismatched trick-or-treat crew serves as comic relief amidst scenes of loneliness and heartache. |

|

| The meter is literally running on the pair’s friendship as Miranda’s confrontation of Carrie serves as a reflection of her own personal and marital flaws. |

It is only once Carrie has made peace with Miranda that she can move forward to reconcile with Big. “There is no right time to tell me that you ruined my marriage,” she spits at Miranda on Valentine’s Day. In fact, there is no marriage to destroy since Big failed to show up. However, the marriage and harmonizing of the four friends is climactic within the film’s plot while Carrie’s marriage to Big takes place almost as an afterthought, part of the film’s resolution.

|

| We are given the elusive image of Carrie barefoot, sans designer stilettos. |

|

| The story of Carrie, Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha continued in Sex and the City 2 (2010) |

This is a guest post by Emily Contois.

I’m not embarrassed to admit it. I totally own the complete series of Sex and the City—the copious collection of DVDs nestled inside a bright pink binder-of-sorts, soft and textured to the touch. In college, I forged real-life friendships over watching episodes of the show, giggling together on the floor of dorm rooms and tiny apartments. Through years of watching these episodes over and over again, and as sad as it may sound, I came to view Carrie, Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha like friends—not really real, but only a click of the play button away.

On opening night in a packed theater house with two of my friends, I went to see the first Sex and the City movie in 2008. Was the story perfect? No. But it effectively and enjoyably continued the story arc of these four friends, and it made some sort of sense. Fast forward to 2010 when Sex and the City 2 came to theaters. I had seen the trailer. I’ll admit, I was a bit bemused. The girls are going to Abu Dhabi? Um, okay. Sex and the City had taken us to international locales before. In the final season, Carrie joins Petrovsky in Paris and in this land of mythical romance, Mr. Big finds her and sets everything right. When their wedding goes awry in the first movie, the girls jet to Mexico, taking Carrie and Big’s honeymoon as a female foursome. But the vast majority of this story takes place in New York City. It’s called Sex and the City. The city is not only a setting, but also a character unto itself and plays a major role in the narrative. So, it seemed a little odd that the majority of the second movie would take place on the sands of Abu Dhabi.

|

| In Sex and the City 2, the leading ladies travel to Abu Dhabi |

Before the girls settle in to those first-class suites on the flight to the United Arab Emirates, however, we as viewers must suffer through Stanford and Anthony’s wedding. From these opening scenes, there’s no question why this dismal film swept the 2011 Razzie Awards, where the four leading ladies shared the Worst Actress Award and the Worst Screen Ensemble. How did this happen?? These four ladies were once believable to fans as soul mates—four women sharing a friendship closer than a marriage. And yet they end up in these opening scenes interacting like a blind group date—awkward, forced, and cringe-worthy.

From the moment our Sex and the City stars have decided to take this trip together, however, Abu Dhabi is viewed through a lens of Orientalism, demonstrating a Western patronization of the Middle East. Starting on the first day in the city, Abu Dhabi is framed derisively as the polar opposite of sexy and modern New York City. It’s also stereotypically portrayed as the world of Disney’s Jasmine and Aladdin, magic carpets, camels, and desert dunes—”but with cocktails,” Carrie adds. This borderline racist trope plays out vividly through the women’s vacation attire of patterned head wraps, flowing skirts, and breezy cropped pants. Take for example their over-the-top fashion statement as they explore the desert on camelback, only after they have dramatically walked across the sand directly toward the camera of course.

|

| Samantha, Charlotte, Carrie, and Miranda explore the desert, dressed in a ridiculous ode to the Middle East via fashion |

The exotic is also framed as dangerous and tempting, embodied in Aidan, Carrie’s once fiancé, who sweeps her off her feet in Abu Dhabi and nearly derails her fidelity. This plays out metaphorically as they meet at Aidan’s hotel, both of them dressed in black and cloaked in the dim lighting of the restaurant.

|

| Carrie “plays with fire” when she meets old flam, Aidan, for dinner in Abu Dhabi |

Sex and the City 2 also comments upon gender roles and sex in the Middle East. For example, in a nightclub full of belly dancers and karaoke, our New Yorkers choose to sing “I Am Woman,” a tune that served as a theme song of sorts for second wave feminism. As our once fab four belt out the lyrics, young Arabic women sing along as well. And yet the main tenant of the film appears to be an ode to perceived sexual repression rather than women’s rights.

|

| The ladies of Sex and the City 2 sing “I Am Woman” at karaoke in an Abu Dhabi nightclut |

Abu Dhabi is a place where these four women—defined in American culture not only by their longstanding friendship, but also by their bodies, fashionable wardrobes, and sexual exploits—must tone it down a bit. For example, Miranda reads from a guidebook that women are required to dress in a way that doesn’t attract sexual attention. Instead of providing any context in which to understand the customs of another culture, Samantha instead repeatedly whines about having to cover up her body. Our four Americans watch a Muslim woman eating fries while wearing a veil over her face, as if observing an animal in a zoo. The girls poke fun at the women floating in the hotel pool covered from head to ankle in burkinins, which Carrie jokingly comments are for sale in the hotel gift shop. In this way, Arab culture is both commodified and ridiculed. And rather than finding a place of common understanding, the American characters are only able to relate to Arab women by finding them to be exactly like them, secretly wearing couture beneath their burkas. While fashion is the common thread linking these American and Arab women, the four leading ladies don’t really come to understand the role and meaning of the burka. Instead, after Samantha causes a raucous in the market, the girls don burkas as a comedic disguise in order to escape.

At this point in the film, the main narrative conflict is again a very white problem—if the ladies are late to the airport, they’ll (gasp!) be bumped from first class. Struggling to get a cab to stop and pick them up, the women have to get creative. In a bizarre twist that references a scene from the first twenty minutes of the film, Carrie hails a cab by exposing her leg, as made famous in the classic film, It Happened One Night. While she gets a cab to stop, one is struck by the inconsistency. The women were just run out of town for Samantha’s overt sexuality and yet exposing a culturally forbidden view of a woman’s leg is what saves the day? Or is the moral of the story that a car will always stop for a sexy woman, irrespective of culture? Either way, our leading ladies make it to the airport, fly home in first-class luxury, and arrive home to better appreciate their lives. No real conflict has been resolved—though a 60-second montage provides sound bites of what each character has learned.

|

| In homage to It Happened One Night, Carrie bares her leg to get a cab to stop in Abu Dhabi |

Throughout the course of Sex and the City 2, the United Arab Emirates doesn’t fair well, but neither does the United States, as the land of the free and home of the brave is reduced to a place where Samantha Jones can have sex in public without getting arrested. Sex and the City 2 stands out as a horrendous example of American entitlement abroad, a terrible travel flick, and a truly saddening chapter for those of us who actually liked Sex and the City up to this point.

|

| Don is being closed in on this season. |

Written by Leigh Kolb

At the Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio, in 1851, Sojourner Truth said,

But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.

|

| Don reading The Inferno. Dante’s journey though hell is not unlike Don’s perception of life this season. |

|

| Dawn briefly speaks to her friend about being a black woman in a very white area and industry. |

|

| Something is missing, Don. |

|

| Michonne in The Walking Dead |

Written by Megan Kearns | Warning: spoilers ahead!

So the season 3 finale of The Walking Dead. What can I say? Is there less sexism than last season’s appalling anti-abortion storyline with Lori’s pregnancy? Did the addition of badass Michonne change the gender dynamics?

It’s also interesting to note that the writers changed the sexual assault survivor from a black woman to a white woman. Too often, the media erases the narratives of black women rape and assault survivors, choosing to focus on white women survivors.

|

| Maggie in The Walking Dead |

|

| Lori and Carl in The Walking Dead |

“I don’t mean to sound sexist, but as far as women have come over the last 40 years, you don’t really see a lot of women hunters. They’re still in the minority in the military, and there’s not a lot of female construction workers. I hope that’s not taken the wrong way. I think women are as smart, resourceful, and capable in most things as any man could be … but they are generally physically weaker. That’s science.”

|

| Crash (2004) |

|

| Crash (2004) |

|

| Mmm…empty calories. Like The Help? |

The perfect summer escape for viewers who embrace the fantasy of a postracial America, [where] filmgoers can tuck the history of race and class inequality safely in the past, even as the recession deepens already profound racial gaps in wealth and employment.

When Tarantino understandably felt uncomfortable with the thought of filming scenes of a slave auction and brutality against slaves, he struggled with not wanting to film those scenes in the American south. He sought advice from Sidney Poitier (the first African American to win a Best Actor Oscar). His response:

“‘Sidney basically told me to man up,’ Tarantino says. ‘He said, ‘Quentin, for whatever reason, you’ve been inspired to make this film. You can’t be afraid of your own movie. You must treat them like actors, not property. If you do that, you’ll be fine.'”

Overall, Tarantino was fine. His Black actors, however, were not recognized for their performances (this was reminiscent of his 1997 film Jackie Brown, which received Golden Globe nods for Samuel L. Jackson and the title character, Pam Grier, but only received an acting Academy Award nomination for white co-star Robert Forster).

In an Oscar year that feature films that deal with race (The New York Times recently published an excellent article examining race and the roles of Black men in this year’s Oscar contenders), the acting awards nominations are startlingly white (Denzel Washington and Quvenzhané Wallis being the exceptions).

[Warning: spoilers ahead!]