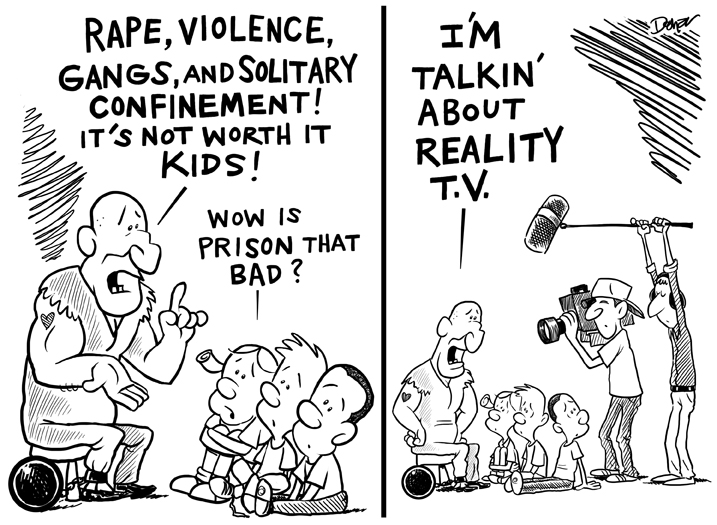

I am too old for the Disney Channel. The bright candy colors, the rapid-fire pacing, the saccharine music and headache-y flash-cuts and forced zaniness – it all adds up to one massively hyperstimulating, sugar-coated migraine. Half an hour of all that on a Saturday morning and I am ready to bounce off the ceiling before crashing to earth semi-comatose for the rest of the day.

If you can overcome (or, better, avoid entirely) the excruciating commercials and the overstimulation of the Disney Channel milieu, however, you can experience maybe the most exciting television debut of 2012. (Not, I’ll admit, that the upcoming fall season looks to offer stiff competition.)

In the nine episodes aired so far, Gravity Falls has already established a pretty dense mythology for itself, jam-packed with occult imagery, cryptograms, conspiracies, clever callbacks, and hidden Easter eggs (and there are already plentyof websitesdevoted to deciphering this stuff). It’s an enormously fun show, chronicling the supernatural adventures of twelve-year-old twins Dipper and Mabel in the creepy, not-quite-right town of Gravity Falls, Oregon. The level of care and detail lavished on the world-building is matched by the depth and – if I can say this of an animated Disney Channel show – realism of the characters.

Dipper and Mabel, voice by Jason Ritter and Kristen Schaal, are wonderfully characterized as not just siblings but true friends: despite their personality differences, they enjoy spending time together, and although they needle and mock each other they always have each other’s back. As somebody whose siblings are my best friends, I find it rings very true to life, and the only other show I can think of with a comparably close sibling dynamic is Bob’s Burgers –where, coincidentally, one of the siblings is also voiced by Schaal.

The twins’ age is a savvy writing choice that allows for some spot-on exploration of themes of growing up, pitching the show niftily at the crossover-hit sweet spot for both younger and older viewers. A grown-up trying to convince other grown-ups to watch a Disney Channel animated show can certainly relate to the twins’ swithering between the childish excitement of their supernatural adventures and their desire to prove themselves cool enough for the local teenagers (including Dipper’s hopeless and completely understandable crush, Linda Cardellini-voiced Wendy). Two specific episodes of Gravity Falls work well as companion pieces exploring Dipper and Mabel’s respective struggles to establish their identities.

Episode 6, “Dipper Vs. Manliness”

|

| A cutie patootie. |

|

|

Dipper is the more introspective, bookish twin – as Mabel puts it, he’s “not exactly Manly Mannington.” When an old “manliness tester” machine at the local diner declares him “a cutie patootie,” Dipper’s insecurity about being a man goes into overdrive, and he seeks training in the ways of manliness from a group of Manotaurs (“half man, half… taur!” “I have 3 Y-chromosomes, 6 Adam’s apples, pecs on my abs, and fists for nipples!”).

Anyone who’s been a feminist longer than five minutes knows that

the enforcement of gender roles harms men as well as women, and this episode features a lot of great jokes lampooning the sheer absurdity of what’s considered manly in our society: the pack of REAL MAN JERKY emblazoned with the slogan YOU’RE INADEQUATE!, the Manotaur council that involves beating the crap out of each other, Dipper convincing the reluctant Manotaurs to help him (“using some sort of brain magic!”) by suggesting they’re not manly enough to do it.

In the end, it’s Dipper’s love for a thinly-veiled “Dancing Queen” pastiche that causes him to defy the Manotaurs’ stereotypical definition of manliness. His enjoyment of something considered “girly” opens his eyes to the nonsensical restrictiveness of traditional gender roles. As he says in his climactic speech to the Manotaurs: “You keep telling me that being a man means doing all these tasks and being aggro all the time, but I’m starting to think that stuff’s malarkey. You heard me: malarkey!”

Rejecting the Manotaur’s version of manliness does not, however, answer Dipper’s agonized question about the nature of masculinity: “Is it mental? Is it physical? What’s the secret?” (And how many times have I myself asked that question?) Although the episode puts a neat bow on Dipper’s arc by offering a pat moral – “You did what was right even though no one agreed with you. Sounds pretty manly to me” – it’s made fairly clear that masculinity and femininity do not have to be discrete, oppositional spheres rooted in stereotypes, and the question of what makes a man is left open – as, perhaps, it should be.

Episode 8, “Irrational Treasure”

Mabel is the best. She’s my favorite character, and with every episode I love her even more. Her quest for self in “Irrational Treasure” is not a direct counterpart to Dipper’s search for manliness – Mabel is pretty comfortable with both the ways in which she is conventionally feminine and the ways in which she is not (reflecting the sad reality that girls’ freedom to express masculinity is not mirrored by an equivalent freedom for boys to express femininity). In the show’s fourth episode, “The Hand That Rocks the Mabel,” she confronts the societal pressures around dating while female, as she struggles with how to extricate herself from a coercive romantic relationship with the creepy Lil Gideon – an object lesson in how messed up are our society’s ideas of the romantic pursuit of uninterested women by persistent men – but in this episode she faces a less explicitly gendered problem: how to convince everyone that she’s not silly.

The delightfully goofy hijinks of this episode – involving a conspiracy to cover up the existence of Quentin Trembley, the peanut-brittle-preserved eighth-and-a-half president of the United States – are propelled by Mabel’s quest to prove her seriousness to rival Pacifica Northwest. Pacifica is a pretty stereotypical stuck-up-rich-mean-girl archetype thus far, but it seems distinctly possible that an interesting character arc could await her in future. “You look and act ridiculous,” she tells Mabel with scorn, and Mabel takes her peer’s cruelty to heart the way only a pre-teen can. “I thought I was being charming,” she says dejectedly, “but I guess people see me as a big joke.”

|

| Don’t worry Mabel, you really are so so charming. |

|

|

As it was Dipper’s non-manliness that ultimately proved him a real man, so it’s Mabel’s silliness that saves the day here, allowing her to crack all the clues for the conspiracy and help President Trembley escape the local police (who, despite being called serious by Mabel, are in fact extremely silly). By the episode’s end, Mabel is impervious to Pacifica’s jibes: “I’ve got nothing to prove. I’ve learned that being silly is awesome.”

Figuring out who you are in the face of societal pressures that buffet you every which way is the trial of growing up, and helping people to do that is one of feminism’s goals. It’s also at the heart of

Gravity Falls, which helps cement this for me as the most exciting new show of 2012. (Plus, it’s apparently

indoctrinating kids into occult symbolism. Cool.)