These techniques are uniquely suited to the onscreen portrayal of adolescence. It almost seems churlish to complain that Water Lilies and Tomboy lack full structural coherence, because that’s arguably intentional. Growing up, after all, is not a tightly-plotted three-act hero’s journey with clear turning points, tidy linear progression through the successive stages of personal development, and a satisfying ending. It’s a messy and confusing struggle to find a place in the world, littered with incidents that may or may not ultimately be significant (with no way to tell the difference), and most of the time the morals make no sense.

Sciamma instinctively understands this, and the little stories she tells of growing up queer are given vivid life through her two greatest strengths as a filmmaker: her ability to coax marvelously deep and naturalistic performances out of her young actors, and her eye for a strikingly memorable little scene that perfectly encapsulates a moment of overpowering adolescent emotion – the normally boisterous Anne clutching at a lamppost and weeping in Water Lilies, for example, or Tomboy‘s Laure curling up on the couch, thumb in mouth, suddenly overwhelmed by an earlier humiliation.

Both films are carried on the remarkably expressive faces of their lead actresses. There are no voice-over monologues or expository conversations, but both Water Lilies and Tomboy present the inner life of their protagonists with stunning depth and rawness.

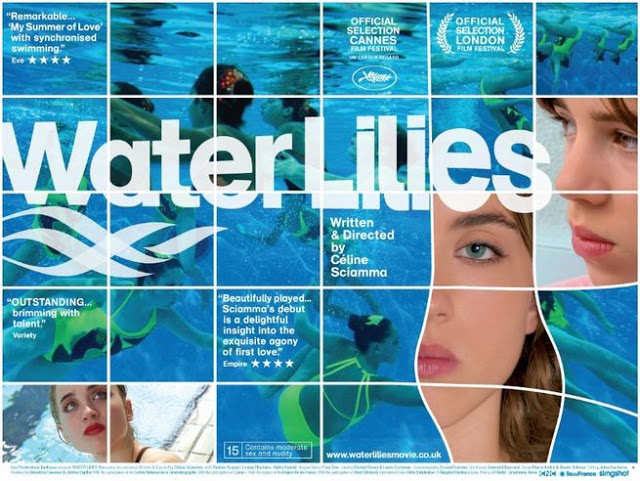

|

| Movie poster for Water Lilies |

Anne, though less conventionally feminine than the other girls, is confidently heterosexual and determined to sleep with the boy she finds attractive. Marie is so eager to spend time with Floriane that she agrees to help her sneak out to meet François, and her yearnings for the lithe bodies slipping through the water are beautifully conveyed through moments such as the shot of Marie shifting, flustered, as Floriane unselfconsciously changes into a swimsuit right in front of her. Floriane herself, despite the reputation she cultivates (perhaps recognizing that denial would be futile – once branded a “slut,” a teenage girl is hopelessly trapped in a no-win morass of contradictory social pressures), eventually confesses to Marie that she has never actually had sex, and in fact is afraid to do so.

“If you don’t want to do it, don’t.”

“I have to.”

“Where did you read that?”

“All over my face, apparently. If he finds out I’m not a real slut, it’s over.”

|

| Movie poster Tomboy |

Any ten-year-old lives in the present, and Mikael meets each challenge as it arises – sneaking away deep into the woods when the other boys casually take a pee break; snipping a girl’s swimsuit into a boy’s, and constructing a Play-Doh packer to fill it; swearing Jeanne to secrecy when Lisa unwittingly tells her about Mikael – even as it becomes increasingly clear to the viewer that eventually Laure’s parents must find out about Mikael. As loving as they are, they still exert some gender-policing of their oldest child: Mom’s delight at hearing that Laure has made a female friend (“You’re always hanging out with the boys”) might have been tempered if she’d remembered that “copine” can also mean girlfriend!

The relationships between the various children are superbly observed, and constitute reason enough to see Tomboy in themselves. The energetic activities of childish horseplay that give Mikael such joy in himself and in his body – dancing enthusiastically with Lisa, playing soccer shirtless, wrestling in swimsuits on the dock – are balanced by the many lovely domestic scenes demonstrating the closeness of Laure’s relationship with Jeanne. This is honestly one of the most moving and genuine cinematic portrayals of a sibling relationship in years, and after her initial shock Jeanne takes to the idea of Mikael like a duck to water, boasting to another child about her awesome big brother, and telling her parents that her favorite of Laure’s new friends is Mikael.

The parents themselves, unfortunately, are much less accepting of Mikael. The film’s ending is ambiguous, allowing for multiple readings of the exact nature of Laure’s queerness; indeed, the film has been criticized as “an appropriation of trans narratives by a cis filmmaker toward her own purposes”; but to me the ending is terribly unhappy. With deep breaths and with profound conflict on Héran’s preternaturally expressive face, the character is forced to claim “Laure,” the name and gender assigned at birth and not the ones of choice. The cissupremacy has won this round.

Though Tomboy is the better film, the two movies make excellent companion pieces. Between them they depict a range of queerness and explore a variety of strategies for growing up queer (and/or female) in a hostile world. And yet they offer no easy solutions, no cheap moralizing, no promise that it gets better. These films, and the characters they portray, simply are. And, in the end, isn’t that the one universal truth of queer people? There is no ur-narrative of queerness. There is no right or wrong way to be queer. We simply are.

Max Thornton is a Bitch Flicks writer, blogs at Gay Christian Geek, tumbles as trans substantial, and is slowly learning to twitter at @RainicornMax.