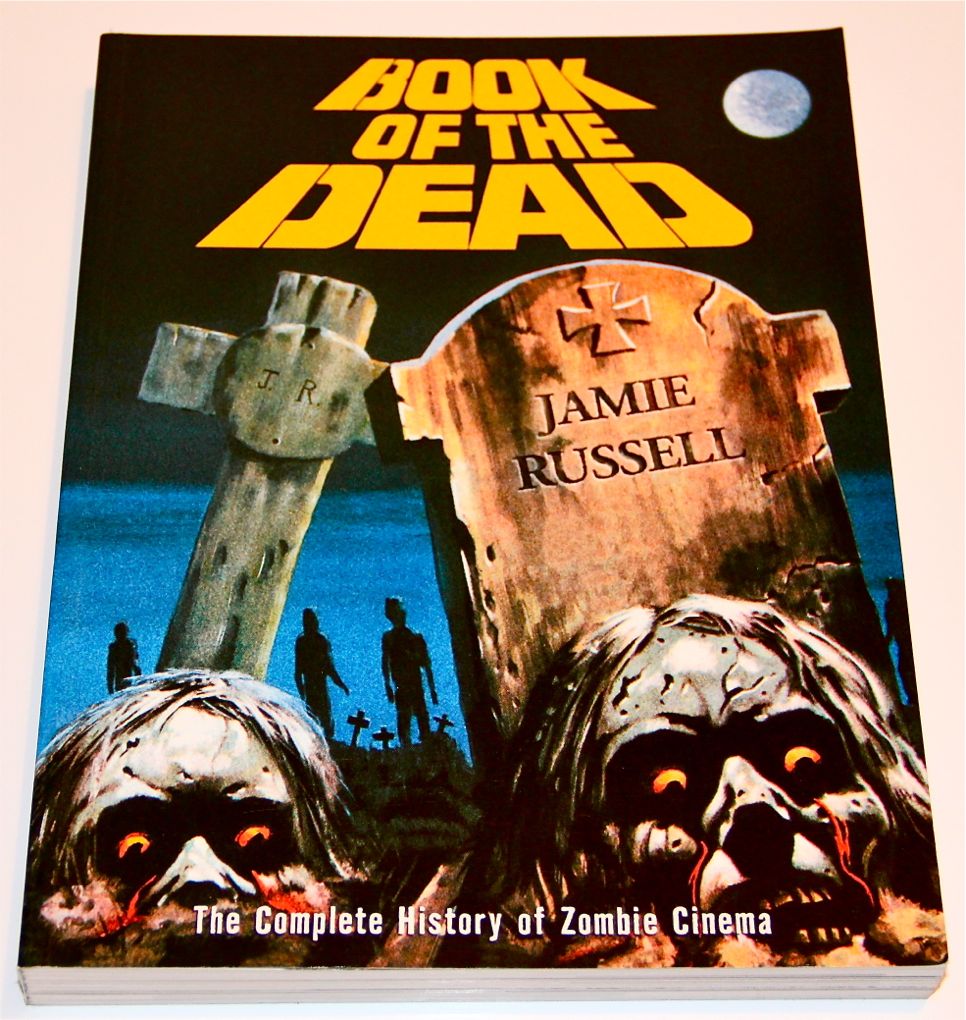

I spent my teen years hopelessly addicted to zombie movies. No matter how poorly made, no matter how artistically worthless, no matter how nasty and exploitative, if the movie had zombies in it, I would watch. The first thing I bought with the first paycheck from my first job at seventeen was Jamie Russell’s Book of the Dead: The Complete History of Zombie Cinema.

|

| In 2006, it was indeed more or less complete, but a LOT of zombie movies have been made since then. |

I should state upfront that I hold no truck with narrow, exclusionary definitions of “zombie.” To me, the zombie is a very broad church: if somebody has ever called it a zombie, it’s a zombie. The Deadites of Evil Dead? Zombies. The Somnambulist in The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari? A zombie. The Dead Men of Dunharrow? Zombies. (Don’t even try that 28 Days Later “infected” crap with me. Those are most definitely zombies, and you should trust me on this because I probably know more about zombie cinema than you.) (Unless you’re Jamie Russell, in which case thank you for stopping by, sir, and I love your book, and I wrote a paper about Zombie Jesus if you’d like to read it?)

As well as being a zombie aficionado, I spent my teen years deep in confusion and denial about sexuality and gender – and these two things are perhaps not unrelated. Vampires and werewolves are explicitly sexual and very gendered, but my movie monster of choice erases sex and gender entirely by its very nature. There are no alluring seductions, no monthly cycles, no explosions of pent-up masculine rage in the zombie: only a creeping sameness and inevitability, all social categories dissolved into nothingness, all physical difference literally consumed in the nightmarish Eucharist of undead cannibalism.

Of course, this erasure of sex and gender does not mean that sex and gender are not explored in zombie films. On the contrary, there are some very interesting things going on, as we shall see in our whirlwind tour of the Three Eras of Zombie Cinema.

Stage One: The Pre-Romero Era

The early stage of zombie cinema is the least popular (and it is also my strongest ammunition in the fight against the purists who insist that only the Romero flavor of zombie – the dead, resurrected, flesh-eating variety – counts as a true zombie). For the first 35 years of its onscreen existence, the zombie didn’t eat anybody’s flesh. Instead, a zombie – first seen in 1932 Bela Lugosi vehicle White Zombie – was a mindless slave resuscitated by voodoo.

The words “voodoo,” “1932,” and “slave” all in the same sentence like that has probably alerted you to the most striking fact about these early zombie films, which is that they are hella racist. In White Zombie, Bela Lugosi plays a Haitian voodoo master who conspires with a plantation owner to zombify a white woman. I Walked With A Zombie (1943) and Hammer’s The Plague of the Zombies (1966) also draw on Haitian voodoo and slave plantations. Per Russell’s thoughtful postcolonial reading of these films, they play on colonial fears of white enslavement and Afro-Caribbean magical powers. In all three movies, the great threat posed by the zombies and their voodoo master is the enslavement of a young white woman.

|

| I Walked With A Zombie: SO MUCH horrendous racial and sexual imagery in one little screencap. |

In these early films, white women exist primarily to be threatened by a monster with a subtext of sexual violence, suggesting the racist narrative of predatory, animalistic black men preying on lily-white women. It’s pretty stomach-churning to watch, even if it’s fascinating fodder for students of gender, race, colonialism, and the cinema. Luckily, in 1968 zombies were revitalized, and their race and gender aspects completely transformed, by one remarkable movie.

Stage Two: The Golden Age

In Night of the Living Dead, George Romero’s most obvious innovation was actually cribbed from the Richard Matheson novella I Am Legend (in which the undead bloodsuckers are actually identified as vampires, though often read as zombies). Like their literary predecessors, Romero’s shuffling reanimated corpses fed on the living. The association of zombies with Haitian voodoo, slavery, and colonialism was jettisoned, and pop culture hasn’t looked back.

Calling this period the golden age is almost entirely a matter of personal preference, but good lord are there some terrific zombie films from the 1970s. Romero’s own Dawn of the Dead is the undisputed masterpiece of the era, but there are some wonderful movies from all across Europe: the Spanish Blind Dead series, Lucio Fulci‘s giallo gorefests in Italy (especially the splendid The Beyond), French film The Grapes of Death, the underrated and transnational The Living Dead at the Manchester Morgue…

But it was Night of the Living Dead that set the tone for these movies, both in terms of the unremitting bleakness and in the heightened consciousness of social issues. Romero has always claimed that his choice of African-American actor Duane Jones for protagonist Ben was color-blind casting, but his own subsequent filmography displays a clear concern for class and race issues. The role of gender in golden-age zombie films is subtler, but no less present. One of the more shocking moments in NotLD is the reveal of the little zombie girl chomping on her dead father and murdering her own mother. The message is clear: the zombie apocalypse breaks down all social categories. The mother-child bond, so often inviolable in Hollywood, is broken in the most violent way imaginable. A little girl, the archetype of innocence, enacts the violence. Social roles cannot possibly hold in the face of the undead threat; in the end, the zombie makes equals of us all.

|

| No wonder I am terrified of preteens. |

Stage Three: The Great Comeback

The eighties and nineties saw a proliferation of slasher flicks, while the zombie fell out of favor. Russell ascribes the zombie resurgence of the past decade to the 2002 double-whammy of 28 Days Later and the video game Resident Evil. Before long, Dawn of the Dead was remade, while Shaun of the Dead gave the genre a simultaneous shot in the arm as the first self-styled “RomZomCom.” By the middle of the decade, zombies were well and truly mainstream.

It’s a curious fact, explored by Carol J. Clover in Men, Women, and Chain Saws, that lowbrow genre fare can sometimes push the boundaries of what’s socially acceptable by mainstream Hollywood standards. Arguably, the mainstreaming of zombies has actually defanged some of their ability to make interesting commentary on gender.

For example, the largely entertaining and in some ways surprisingly innovative 2009 zom-com Zombielandends with its previously strong, capable female characters screaming on an amusement park ride, needing to be rescued by the male protagonist. While 1970s zombie films didn’t exactly lack delicate fainting ladies, there was an overall thematic sense that the rising of the dead renders categories such as gender roles ontologically insignificant. A film like Zombieland manages to use the zombie apocalypse to actually enforce gender stereotypes. Similarly, I rage-quit AMC’s The Walking Dead after one season, in part based on a scene where the female characters had a discussion along the lines of, “Well, the apocalypse has hit; better revert to traditional gender roles, ’cause cavemen!!”

I still love zombies deeply. I love the wish-fulfillment aspect of imagining yourself as the last brave outpost of survival against the onslaught, creating your own beleaguered little society when this one collapses. I love the multiplicity of symbolic potential in the zombie, the seemingly endless variety of fears for which it can stand: the inevitability of death; infiltration of human-seeming replicants or pod people; fear of brainwashing or enslavement; loss of all particularity or individuality; uprising of the faceless proletariat; the revenge of Gaia; communism; enforced conformity; being overwhelmed by whatever force it is that you fear most (feminism or kyriarchy or theocracy or secularism or or or…).

But I’m experiencing burnout. I don’t enjoy seeing such a rich, challenging, bleak, existential symbol stripped of all its nuance to cater to the same old reductive Hollywood tropes and narratives. I’m sick of the mainstream cultural attitude toward gender and social roles, and I am very sick of seeing things I love harnessed to serve this attitude.

|

| It makes me want to eat somebody’s brains! Which is a thing invented in Return of the Living Dead in 1985. |

Max Thornton blogs at Gay Christian Geek, and is slowly learning to twitter at @RainicornMax.

I wrote a musical (yes! zombie musical, woo!) in which I subverted the roles of humans and zombies in society, taking my cue from the first-phase voodoo zombie movies and completely flipping it on its head. The zombies in my show are the protagonists (they’re sort of like misunderstood frankenstein types), and the humans are living in a society of enforced conformity. My main protagonist is a girl called Lila who is turned into a zombie and has to help her new zombie friends escape destruction by the “mindless” humans. The zombie transformation in my show is a long process, and it takes a couple of days before they lose all human values. It was fun to research zombies and twist some ideas.

P.S. I love this blog! Currently reading all the horror week entries to help me with an essay I’m writing on the trailers for the new Evil Dead and Carrie films.