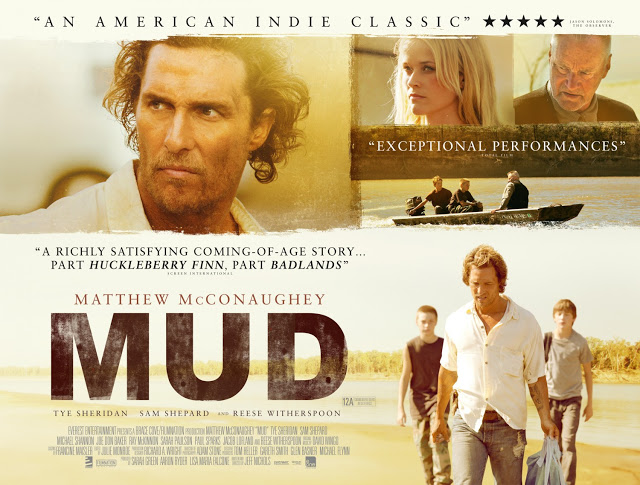

|

| Matthew McConaughey all over the movie poster for Mud |

I wanted to see

Mud because it looked like an interesting film about the cult of masculinity. It is, in fact, a film about masculinity and father-son relationships, but it goes out of its way to avoid offering an actual

critique of masculinity. If anything,

Mud celebrates the masculine by demonizing the feminine. The women in this film carry the sole responsibility of ruining every dude character’s life, and

Mud screams through a megaphone its Women Are Awful message from the first scene all the way to “Help Me, Rhonda” playing over the closing credits. And I thought

Side Effects was bad.

I hated that I had to hate

Mud; the young boy who plays Ellis (Tye Sheridan) and his best friend Neckbone (Jacob Lofland) blew my mind, and Matthew McConaughey as Mud gave his best performance since

Ghosts of Girlfriends Past (ha). Reese Witherspoon somehow even managed to garner sympathy for a second with her ten minutes on screen, a serious feat given the fact that the character she plays (Juniper) gets blamed by everyone for Mud’s predicament as a fugitive in hiding. Ellis’s parents, too, particularly Sarah Paulson (as Mary Lee) of recent

American Horror Story: Asylum fame, gave moving performances, and I especially liked Michael Shannon’s three brief scenes as Galen—not because anything other than sexism and man-childness occur—but because he always commands the screen (see

Take Shelter and

Revolutionary Road). The actors, specifically the two young boys, save this film from entirely shitting all over itself.

|

| Jacob Lofland (Neckbone) and Tye Sheridan (Ellis) in Mud |

Matthew McConaughey plays Mud, the title character, and I keep reading everywhere that Mud is a retelling of Huck Finn, so okay. Two 14-year-old boys, Ellis and Neckbone (best. name. ever.), live in a poor yet quaint and lovely town on the Mississippi River. In conventional boys-as-adventurous-explorers fashion, they sneak their small boat off to an island down the river where they find an abandoned boat stuck in a tree. After climbing up there and sifting through a treasure trove of Penthouse magazines (because that’s necessary) and finding a bag of canned beans, they realize someone lives on the boat. Mud! The rest of the film shows men bonding with one another by objectifying women, beating up men to defend the honor of women, and blaming women both for the abuse inflicted upon them by men and for the problems they “cause” for the men around them. It’s a real win-win for the ladies of Mud.

|

| Ellis goes to find Mud on the island |

There is not a woman in this movie who doesn’t betray her man, cheat on him, use him, steal his home, rob him of his authenticity, make him move to a boring condo complex in the suburbs, or otherwise force him [out] of his natural and driving male essence … This thing might as well be a river fort with a giant “No Girlz Allowed” sign out front.

Hard to argue with that. Here’s why.

I guess I knew in pretty much the first scene (and in the first lines of dialogue), when Ellis told Neckbone he had a crush on a girl and Neckbone responded with, “She’s got nice titties,” that Mud might walk a fine line between either existing as a coming-of-age tale or offering up a sexist piece of shit under the guise of a coming-of-age tale. It’s a little bit of both.

|

| The freakshow Ellis and Neckbone see when they first meet Mud |

Sounds romantic, right? See, I definitely teared up during its most manipulative moments, and I definitely came to care about the characters, and I definitely wanted to leave the theater feeling okay about that rather than feeling guilty for liking a movie that portrayed my gender (and even men), with such simplicity and disrespect. I psychically begged Mud to reverse all its misogyny in the end, to somehow invalidate the sexist ideology it spent nearly two hours enforcing, so that I could write about its complexity and nuance and be all, “Wow, what a smart deconstruction of Southern masculinity!” No dice.

Instead, I get to write about typical Hollywood gender-trope drivel, except it exists in a fucking semi-indie film, and, according to me—a genius—indie films ain’t supposed to rely on Hollywood gender-trope drivel anymore. Let’s begin.

|

| Best Fucking Friends Ever |

Every man in this movie tells a story about a woman who wronged him. Every. Single. One. The opening scene (juxtaposed with the “nice titties” comment and the Penthouse porn) shows Galen, Neckbone’s uncle and sole caretaker, getting reamed by his girlfriend. She bolts from his home, whips around to find the two boys sitting on the porch, and says something like, “You make sure you always treat girls like princesses!” We quickly learn that Galen tried something in bed that his girlfriend didn’t like, so when she throws a handful of gravel at him and yells, “I’m a princess!” Galen and the boys (and the audience) laugh at her “irrational” reaction and prudishness. Boys will be boys, honey.

|

| Michael Shannon as Galen, aka Misogynist of the Year |

Ellis and Neckbone then leave the house carrying Galen’s book on how to understand the opposite sex (because that’s necessary), and the film officially begins its Women Are Awful message with not even a hint of fucking subtlety or irony: welcome to prudes, princesses, titties, Mars/Venus, hysteria, virgin/whore nonsense, and porn, all within the first five minutes of screen time.

Not surprisingly, we learn that Mud finds himself stuck on an island and running from the law because of Juniper, a woman he fell in love with as a young teenager. The film pulls no punches in its insistence on blaming Juniper for Mud’s situation; she involved herself with an abusive man—a pattern for her—and since Mud lurves her so much, he obviously needed to murder the man responsible for beating her and causing her to miscarry. Juniper’s beating also destroyed her reproductive system (why not?), and that factors strongly into Mud’s decision to kill. The message here, and Mud all but says it, is that robbing a woman of her God-given responsibility to bare children is unforgivable and punishable by death.

I wish that were the only instance of blaming a woman’s reproductive capacity for another man’s misery, but, alas, Tom (a possible former CIA assassin, played creepily by Sam Shepard) can barely stand to interact with anyone ever since his wife and son died during childbirth. He raised Mud as his own son (only Ellis knows his biological father, played by Ray McKinnon), and sits on the river shooting his gun every now and then like a hater. Basically, women are misery-inducing killjoys who suck at performing their duties of procreation.

|

| Sam Shepard waiting to … kill … something? |

When women deign to momentarily stop holding hostage the broken hearts of men everywhere, they fall into the coveted category of Desired Object, going from active life ruiners to passive beauty queens.

|

| Reese Witherspoon as Juniper with Smeared Mascara |

We first meet Ellis’s girl crush (presumably the one with the nice titties) when Ellis sees an older boy put his hands all over her in the parking lot of the Piggly Wiggly. May Pearl (the next best character name after Neckbone and Mud) pushes away the sexual harasser, but do you think that stops Ellis from charging through the parking lot with reptilian stealth and jacking a high school senior in the jaw? No way. That would mean

not employing the Damsel in Distress trope, and, in turn, allowing women to wield their own authority and agency. But

Mud gives no fucks about women other than how they push the male-focused plot forward.

As Megan Kearns notes in her review of Iron Man 3:

The problem with the Damsel in Distress trope is that it strips women of their power and insinuates that women need men to rescue or save them. And yet again it places the focus on men, reinforcing the notion that society revolves around men, not women.

|

| The Piggly Wiggly: after-school hangout |

Interestingly Upsettingly Predictably, the moment that moves Ellis away from rescuing May Pearl—after she rewards him with a kiss and tells him to call her, in typical Damsel in Distress trope fashion—relies on even more misogyny. The congregation of boys in the lot stops their commotion cold when Juniper suddenly appears—in all her blonde-haired glory and cut-off daisy dukes—and saunters into the Piggly Wiggly. The boys gape at her. The teenage girls squirm all jealous. And my brain jerks from all this Sexist Whiplash.

To rewind and parse: a boy street harasses a girl; another boy saves her from said harassment (Damsel in Distress); she publically rewards him for saving her; Juniper shows up as Desired Object; women become jealous of one another over male attention; and Ellis and Neckbone begin their inevitable lightweight stalking of Desired Object. In the span of three minutes.

Okay.

|

| Juniper as Desired Object with Black Eye |

It gets worse, though, way way worse. Later, Ellis and Neckbone find one of Mud’s bounty hunters, who was hired by the father of the man Mud murdered (hi, alliteration!), beating the crap out of Juniper in a motel room off the highway like, “Bitch, tell me where Mud’s hiding OR ELSE.” (Stalking women comes in handy sometimes, for both bounty hunters and young boys.) Naturally, the boys save our resident Damsel in Distress by bursting through the motel room door at just the right moment and pretending to sell a cooler full of fish (ha). The mob thug smacks Ellis down too, though, and that’s when the film finally turns into the Southern gothic crime thriller I’d been hoping for—but not before Juniper rewards Ellis with a kiss for saving her.

LIKE, ARE WE IN FUCKING SUPER MARIO BROTHERS?!?!?!

|

| May Pearl smiles at her knight in shining armor |

The abuse of women in Mud, which serves no purpose other than to normalize domestic violence for the viewer, is horrifying in its own right, but I ultimately found the Blame the Victim ideology the most disturbing aspect of Mud. Not only does the film voyeuristically depict the harassment and physical abuse of women at the hands of men with no critique or analysis, but it also shows the male characters verbally blaming women for the abuse inflicted upon them. Tom, who acts as a father figure to Mud, delivers a lengthy monologue to young Ellis all but calling Juniper a no-good whore for getting involved with so many abusive jerks and ruining Mud’s entire Nice Guy™ life. (You know, because Women Are Awful and consequently at fault for all the choices men make, including their choices to beat the shit out of women.)

|

| Sarah Paulson as Mary Lee in Mud |

The film’s message devolves even further to insinuate that—because Mud hasn’t been physically abusive toward Juniper and has even heroically punished the men who have been—he has both earned and deserves her love. And so, the audience can’t help but dislike Juniper when the boys catch her slutting it up at a bar with a billiards-playing bro instead of sailing off to Mexico with Nice Guy™ Mud in his fixed up former tree boat. A small part of me waited for the film to pause on Juniper’s face for a moment and toss up an UNGRATEFUL BITCH title card, just to make sure the audience got the point.

|

| Juniper, aka UNGRATEFUL BITCH |

The takeaway to the story seems to be that the only people you can count on in this world are your male friends and your father figure. At the end of the movie, after all hell breaks loose as Ellis and Neckbone’s entanglement with Mud gets crazy and deadly, we see each male character have a touching moment with his father figure. None of them are any good—Ellis’ father can’t make money, Mud’s adopted father is a deadly “assassin,” and Neck’s uncle treats women possibly the worst of any of them—but, heck, in a man’s world it’s the man who teaches you how to man like a man that man man man. And some of the man manning that men masculine you with is hatred of women. Ellis’ father … tells him at one point, “Women are tough. They set you up for some.” Eventually, when Ellis confronts Mud about how much girls suck, Mud replies, “If you find a girl half as good as you, you’ll be all set.” See, a woman can never be as good as a man.

|

| Ellis and Mud talk about Being a Man probably |

I can already hear the arguments. Mud exposes the hyper-masculinity present in Southern culture! The boys don’t know any better! That’s just how it is down there! Maybe. But, an intelligent film might consider taking that harmful social construct to task rather than rewarding the male characters for their sexist behavior. Mud presents misogyny as endearing for fuck’s sake, and art—in my opinion—possesses a responsibility to challenge those constructs because it also possesses the power to change them. The dudes in Mud experience no consequences for their bullshit; the film, in fact, revels in their Women Are Awful blues and invites the audience to participate. I’m less interested in whether the depiction of Southern masculinity is authentic. Why not make a statement about how that authentic Southern masculinity hurts women and men?

It never comes close to saying that. But it does manage to deliver a much more cynical message.

|

| Ellis and Neckbone, rightly looking a little terrified of Mud |

Halfway through the film, Galen says to Ellis, “This river brings a lot of trash down. You gotta know what’s worth keeping and what’s worth letting go.” Sure, he’s referring to literal trash (as he points to a newly repaired chandelier he found in the river), and he’s referring to Mud, a known fugitive (because he’s seen Ellis and Neckbone hanging out in the river with Mud), but—make no mistake—he’s also referring to women. The film never stops telling us that Women Are Awful, worthless, disposable.

In the end, Ellis’s dad comes to terms with his wife leaving him; Mud finally moves past Juniper; Ellis ogles a new girl (in slow motion!) after May Pearl breaks his heart in public; even Tom learns to leave the death of his wife behind. The men’s collective triumph becomes the fact that they finally learn to let go of The Trash in their lives and hold onto what’s most important—their relationships with other men. So while Mud is a coming-of-age tale in the traditional sense, and coming-of-age tales deliver all kinds of important messages for their young protagonists to absorb, the film mostly wants Ellis to learn that sometimes you just need to fucking drop a bitch.

How sweet.

|

| How sweet, indeed |

|

|

|

|

|