|

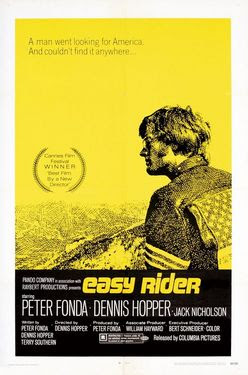

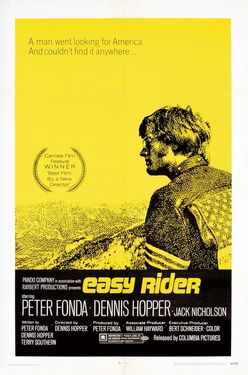

| Easy Rider poster: “A man went looking for America. And couldn’t find it anywhere…” |

Written by Leigh Kolb

|

| Wyatt (Peter Fonda), left, and Billy (Dennis Hopper) search for America. |

|

| Wyatt (“Captain America”) and Billy ride toward what they expect to be the American Dream. |

On the way, they stop at a ranch for a tire fix and dinner. Wyatt is clearly taken by the “simple” life of the rancher and his wife and children. The rancher notes, after learning that Wyatt and Billy are from Los Angeles, that he set out to go there long ago, but “you know how it is,” he says, indicating that he got married and had children instead. His “settled” life isn’t maligned, but is shown as a respectable choice. Wyatt tells the rancher he should be “proud” that he can live off the land. They eat together and are connected by this communal act.

Wyatt and Billy pick up a hitchhiker, and he takes them to his commune. This is a largely feminine space–the women are leaders and nurturers, and have sexual agency. While they are attempting to create an idyllic society, it’s clear that they have substandard soil and questionable farming expertise. Wyatt is optimistic about their future (while Billy thinks they don’t have a chance). The two swim with two women, and they are nude and playful. Male nudity is more present in this baptismal scene than female, and it’s clear that they are having fun. The women are not objects in this film–they are supporting characters, but they are individuals. Throughout, the female characters’ names are more prominent than the men’s, which indicates their individuality.

The women in Easy Rider are nurturers, caretakers, mothers and lovers. Two of the soundtrack’s most prominent songs–“It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” and “Born to Be Wild”–address women. While we often think that a story like this is made possible by the male privilege of being able to be safely alone on the road, it’s clear that that notion is supposed to be challenged.

George has an influential father in town (the sheriff promises to not tell his father he was so drunk), and it’s clear that he has a strong desire to be an activist and effect change, but he’s stuck in between his father’s footsteps and alcoholism, feeling like he can’t move forward because people are so backward. He is another model of American masculinity, not quite fully counterculture, but enough to feel excluded. In jail, he says to Wyatt and Billy, “We’re all in the same cage here.” For these three, that cage is a white patriarchy that has strict social norms that they do not adhere to.

|

| Wyatt, George and Billy get out of jail free–but not quite. |

Wyatt, Billy and now George by association are otherized because they don’t look or behave like “real” men should. The three are attacked that night at their campsite, and George is killed. This violence would surely be justified by the entrenched idea that the townspeople were protecting their women, or even protecting the order of their town by eliminating those who don’t fit.

|

|

A local says, “I guess we’d put him in the women’s cell, don’t you reckon?”

|

“But talkin’ about it and bein’ it, that’s two different things. I mean, it’s real hard to be free when you are bought and sold in the marketplace. Of course, don’t ever tell anybody that they’re not free, ’cause then they’re gonna get real busy killin’ and maimin’ to prove to you that they are. Oh, yeah, they’re gonna talk to you, and talk to you, and talk to you about individual freedom. But they see a free individual, it’s gonna scare ’em.”

They don’t run from fear, though, they get “dangerous.” Resistance to civil rights, to women’s rights, to questioning gender norms–this resistance is typically violent, and is bred by fear of disrupting the social order (that is, the white-supremacist patriarchal order).

Wyatt and Billy make it to New Orleans, and go to the House of Blue Lights (the brothel that George had been excited about). There is heavy religious imagery in this scene–the Latin “Kyrie Eleison” (“Lord have mercy”) as a soundtrack and images of Madonna and child, the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ are everywhere.

While Billy is awkward yet eager with Karen, a prostitute, Wyatt seems uncomfortable and disinterested in the woman he’s “chosen” (her name is Mary–of course).

The four wander into the streets, where Mardi Gras is in full force. Out in the crowded streets, Wyatt kisses Mary and lifts her up, finally feeling comfortable and free.

|

| The four split LSD in the cemetery. |

The four take LSD, and the iconic scene at the St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 gets under way. The sounds of construction are a backdrop to children reciting Catholic prayers as the four characters strip, have sex, weep and trip their way around the cemetery. This is America. Wyatt cries and begs atop a statue of the Virgin Mary (Hopper had directed him to act like he was speaking to his mother, who committed suicide when he was a child). A film critic calls this scene a “eulogy” to the 60s, the end of the hope and optimism that drove liberation and counterculture movements. The trip is chaotic and disappointing.

|

| Wyatt weeps in anger over his mother. |

Wyatt and Billy camp out, and Billy is ecstatic about their journey. “We’re rich man, we’re rich.” Wyatt responds, “We blew it,” without the same pride and excitement for their future. “You go for the big money and then you’re free,” Billy says, encapsulating the American Dream. “Goodnight man,” Wyatt says, rolling over so the large American flag on the back of his jacket is prominent.

They continue riding across America, through its towns and countryside, with shipyards, industry, bridges, factories and the automobile as reminders of the American landscape.

|

| Billy’s defiance and his death. |

Two locals drive by, wanting to “scare the hell” out of Billy. Billy flips them off, and the man asks him why he doesn’t get a haircut. He then shoots him point-blank. Wyatt turns around and promises to go for help as he drapes his flag jacket over Billy. The America that Wyatt has been searching for is lost. As he rides away, the same truck turns around and shoots at him, and his bike erupts in flames.

The camera slowly pans out, so that the speck of fire becomes less and less prominent in the beautiful countryside.

The murder of Wyatt and Billy at the end of the film is senseless, and based in the fear that George described and also the killers’ desire to prove and establish power and dominance. This death is symbolically a death of a hope in an America that is truly free and worth finding. The disappointing freedom of Mardi Gras has made way for the rigid control of lent.

In the almost half a century since Easy Rider was released, it’s chilling how much of the rhetoric and violence against non-conformity and social progress still exists. This dream of an America that Wyatt so desperately wanted to find–a place of freedom and equality where you could live as you desired and “do your own thing in your own time”–went up in flames, just like his flag-emblazoned bike.

“I wasn’t born to follow” (by the Byrds, played while they are swimming naked) also addresses women, although the melody itself was (ironically) written by Carole King.

While they are tripping, Karen (Black) says “I can feel on the outside, but I can’t feel on the inside”–and strips off her clothes behind a tombstone, which I think qualifies as a harrowing feminist statement, intended or not. The legend is that they were tripping for real, and I’ve always believed it.

Lots of us actually went on journeys remarkably like that… I ended up stuck on one of those crazy hippie farms for a week or so. (LOL) It was an intense movie at the time, because so many of us felt that it was right out of our own lives.

BTW, the prostitute named Mary was Toni Basil… yes, THAT Toni Basil (“Oh Mickey you’re so fine, you’re so fine you blow my mind, hey Mickey!”) My daughter refused to believe it for years… I finally had to wait until the invention of Wikipedia to vindicate me. 😉

Wow. Thank you for your words here, Leigh. As a child of the 70s, this movie along with Billy Jack, Jesus Christ Superstar, The Holocaust and Roots helped shape the woman I am today. I’m so thankful that my parents allowed me to watch those movies and TV shows. Allowing me to do so created not just tolerance, but acceptance of the many cultures in our world. If only hate would stop breeding.

– Becky S.