|

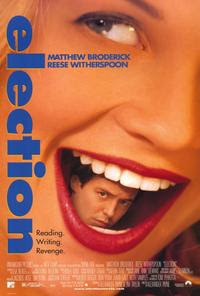

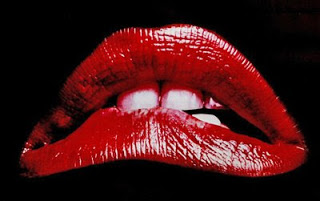

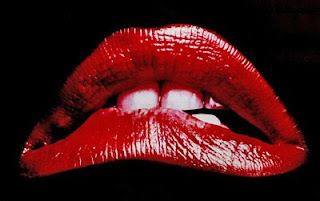

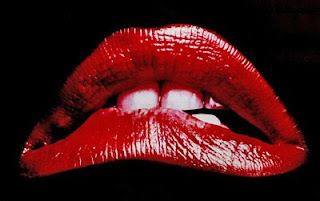

| The lips in the opening sequence–the biting action has sexual and fearful connotations. |

The cult classic film

The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which was based off a British play of the same name, was released in 1975. At that point in American history, audiences (young audiences especially) were eager to have their boundaries pushed and revel in the debauchery that

Rocky Horror provided. Whether it was the after-glow of the sexual revolution of the 60s and early 70s or a preemptive strike back to still-noisy social conservativism,

Rocky Horror dealt with issues of gender and sexuality in a way that can resonate with viewers almost 40 years later. Buried beneath the campy music and bustiers is strong commentary on religion, gender and sexual norms, social customs and puritanical morality.

After the opening sequence (in which the famous red lips–belonging to Patricia Quinn, who plays Magenta–lip sync to Richard O’Brien, who plays Riff Raff and wrote the original play and screenplay, singing

“Science Fiction/Double Feature”), the first shot of the movie is a cross atop a church steeple. The camera pauses, making the audience absorb the contrast between a clearly sexual (and even fearful), disembodied mouth and Christianity.

As the camera pans down, a wedding party and guests burst through the doors of the church. Outside of the church doors, a solemn-looking Tim Curry appears as the pastor, and Quinn and O’Brien flank him in the style of the American Gothic painting by Grant Wood.

We will see this image again. It will never really leave us.

|

| The actors who will appear later as Magenta and Riff Raff play American Gothic in the first scene at the church. |

According to the Art Institute of Chicago, “American Gothic is an image that epitomizes the Puritan ethic and virtues that he [Wood] believed dignified the Midwestern character.” Puritanical “virtues” are on display in this opening sequence.

As American culture reminds us, when these virtues are imbedded in a society, often the only option for sexual expression is at the extremes of the virgin/whore dichotomy. Suppression and purity on one end of the spectrum, complete surrender to earthly pleasure, no matter the cost, on the other. These extremes are shown throughout the film.

As the wedding comes to an end (and after Janet, played by Susan Sarandon, has caught the bouquet), a car pulls up to take away the bride and groom. Sloppily written on the side of the car is, “Wait till tonight, she got hers now he’ll get his.” The heteronormativity of this scene is clear. Women (including Janet) are eager for marriage, men want to “get theirs” after the wedding is over. Janet’s boyfriend, Brad (Barry Bostwick), does quickly propose to her after they discuss marriage in the church cemetery as a storm brews overhead. A billboard with a heart and the motto “Denton – The Home of Happiness” looms above them. The marriage ritual and social expectations surrounding it are, on the surface, celebrated in this scene (

“Dammit, Janet, I love you!” sings Brad as they rollick around the church). However, the symbolism of the cemetery, the pending storm, and the fact that the American Gothic characters are preparing the church for a funeral as they wheel in a casket is not lost on the discerning viewer.

The two set off on a road trip to announce their engagement to a professor they’d had in college (they met and fell in love in his class). On the way, as they drive through a thunderstorm while listening to Nixon’s resignation speech on the radio (perhaps a nod to moral failure), they blow a tire. They end up at a foreboding castle (one used in many

“Hammer Horror” movies that

Rocky Horror parodies), and motorcycles pass them on the road going to the same destination. Brad says of the biker with judgment, “Life’s pretty cheap for that type.” An “Enter at Your Own Risk” sign invites the couple into the castle grounds, and they do.

After Riff Raff lets them in, they’re quickly initiated into the party that’s being held–the “Annual Transylvanian Convention.” They stand, innocent and wide-eyed, as guests (all dressed in gender-neutral tuxedos) dance the

“Time Warp” and thrust their pelvises. The American Gothic painting, as well as the Mona Lisa, both appear on the walls of the castle.

|

| Riff Raff welcomes Brad and Janet to the castle; the American Gothic painting looms behind him. |

PBS art commentator Sister Wendy Beckett

says, “You can recycle the Mona Lisa any way you like. Back to front, upside down, it remains instantly recognizable. That’s the ultimate compliment and it’s been paid to Grant Wood’s American Gothic. Somehow it seems to speak to the American psyche, though what it actually says isn’t as simple as it might seem.” The coyness of these particular works of art mirror what lies beneath

The Rocky Horror Picture Show.Brad and Janet are visibly uncomfortable in this world (it seems “unhealthy,” Janet says). They, and the audience, which has seen the action from their naïve perspective, are then introduced to Dr. Frank-N-Furter, played by Curry. The camera pans up his fishnet-clad legs, reminiscent of the gratuitous male gaze present in so many other films. However, this time the object of that gaze is a

“sweet transvestite from Transsexual, Transylvania,” as he introduces himself in song.

|

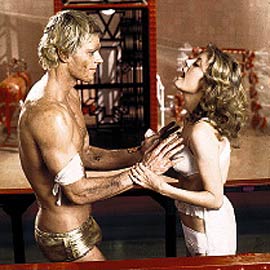

| Dr. Frank-N-Furter introduces himself to Brad and Janet. |

He invites the couple up to his lab to “see what’s on the slab.” They are stripped to their underwear by Riff Raff and Magenta (“We’ll play along for now,” says Brad). On their way up to the lab, Janet asks Magenta if Frank-N-Furter is her husband. She laughs, and Riff Raff exclaims that he’ll probably never marry (again, marriage is slighted). Frank-N-Furter has changed into a scrubs-style dress (with a

pink triangle on the chest) in the lab. He flirts with Brad, calling him a “force of manhood, so dominant,” and Janet begins to giggle and seem less uncomfortable in this new setting. Being stripped of their clothes leaves them almost naked and vulnerable, yet opens them up to sexual possibilities that explore gender and dominance.

|

| Frank-N-Furter, seated, flanked by (from left) Columbia, Magenta and Riff Raff–all of whom he as used for his gain. |

Frank-N-Furter announces that “My beautiful creature is destined to be born!” and the references to Frankenstein throughout the film thus far are fully realized. He climbs above the tank that is holding his “creature,” and drops in rainbow-colored liquid, leaving the creature awash in the rainbow. (In 1975, the rainbow flag had not yet been formally adopted as the LGBT

banner, but rainbow flags were commonly used for similar liberal causes starting as early as the late 1960s.)

After his creature is born–a muscular, blonde, tan god–Frank-N-Furter ogles and gawks at his creation, chasing and crawling after him, scrambling to even kiss his foot. Rocky (his creature) doesn’t seem interested at all, as he sings about feeling the

sword of Damocles above him. As history (and science fiction, like Mary Shelley’s

Frankenstein) has repeatedly shown us, when we create a system in which others are to be subservient–whether via imperialism, slavery or patriarchy–the outcome is only good for those in power, and even then the reward is short-lived.

But for now, Frank-N-Furter appears to be getting his way (after ridding himself of Eddie, played by Meat Loaf, who we find out was an ex-lover of Frank-N-Furter and Columbia, played by Little Nell). Masculinity is magnified in this scene as Frank-N-Furter

sings about making Rocky a “man” through intense physical workouts and bodybuilding routines, and Eddie’s

display of hyped-up violent masculinity (motorcycle, leather jacket, rock and roll). But who is the dominant one in these relationships? Frank-N-Furter, in his fishnets and heels. As heteronormative as the opening scene of the film was, at this point almost all of the lines have been or are beginning to be subverted and blurred.

Frank-N-Furter and Rocky walk out of the lab arm in arm as the wedding march plays and his guests shower them with confetti. The curtain is drawn as they embrace, and the audience expects that they will consummate this “marriage” immediately.

In the middle of the night, Rocky escapes the wrath of Riff Raff and Magenta (he has chains on his ankles as he attempts to flee).

Janet and Brad have been put in separate rooms, of course, so they may retain their pre-marital chastity.

While his creation attempts to escape, Frank-N-Furter visits Janet. He acts like he’s Brad, and she welcomes his embrace and sexual advances. When she figures out it is Frank-N-Furter, she kicks him off: “I was saving myself!” she cried out. After a moment of rough persuasion, she lies back. “Promise you won’t tell Brad?” she says, and laughs as Frank-N-Furter descends upon her.

Afterward, “Janet” visits Brad, and he also welcomes the embrace until he realizes it’s Frank-N-Furter. The scene plays out exactly as it does with Janet–persistent refusal and then “You promise you won’t tell?” Again, Frank-N-Furter moves downward on Brad.

These scenes are poignant in that they are exactly the same–from the strict puritanical refusal to the “secretive” consent to the oral sex act itself–yet the sex of the participants is fluid. Frank-N-Furter is on top, but he’s adamant that the two give themselves “over to pleasure,” which he delivers.

(It’s also worth noting that during the sex scenes others in the house–Riff Raff, Magenta and Columbia–can watch via monitors that display live feed from the rooms. Voyeurism isn’t off-limits, either. Like most issues in this film, there is vast gray area in regard to consent that we are challenged to think about.)

By the next morning, Janet is crying and feeling immense guilt about betraying Brad. However, she happens upon a monitor showing him smoking a cigarette on the edge of his bed, which Frank-N-Furter is lying in. She then spots the injured Rocky, and tends to him. He touches her hand, and she smiles a smile that indicates she has found within herself power and passion.

Janet then bursts into her climactic

song, “Touch-a, Touch-a, Touch-a, Touch Me,” a sex-positive female power anthem if there ever was one. She decries her years of avoiding “heavy petting,” since she thought it would only lead to “trouble and seat wetting.” While the narrator says that Janet was “its slave,” it’s more clear that she is sexually dominant in this scene.

|

| After a lustful night with Frank-N-Furter, Janet embraces her sexuality with Rocky (she places his hands on her breasts). |

Even in her critique of the woman’s stray curl in American Gothic, Sister Wendy

senses something beyond the surface: “Some see the stray curl at the nape of her neck as related to the snake plant in the background, each one symbolizing a sharp-tongued ‘old maid.’ Sister Wendy sees in the curl, however, a sign that she is not as repressed as her buttoned-up exterior might indicate.” Nothing is quite as it seems.

After a cannibalistic dinner (insert corny pun about Meat Loaf here), everything seems to be falling apart. Eddie’s uncle–the Dr. Scott who Janet and Brad were trying to visit in the first place–comes to the castle (he’s both looking for his nephew and doing research on alien life forms). Dr. Frank-N-Furter, seeing everything he’s built to serve himself revolt (Riff Raff, the “handyman,” and Magenta, the “domestic,” are getting antsy to leave to go home to Transsexual; Columbia screams at him for just taking from people–first her, then Eddie, then Rocky, etc.–and Rocky isn’t working out as he planned), clings on to whatever power he can. He mocks Janet and her sexual inadequacy–“Your apple pie don’t taste too nice”–and turns all except for Riff Raff and Magenta into stone via his Medusa switch (the

mythology echoing that of Damocles’s sword and what happens when one demands too much).

“It’s not easy having a good time,” Frank-N-Furter laments.

The floor show that follows is a spectacle of gender and sexuality. The stone figures are “de-Medusafied” one by one, and all are wearing kabuki face makeup and Frank-N-Furter-style fishnets, heels, garters and bustiers. They each

sing a stanza exploring their current state of drug dependence, uncontrolled libido and freedom in “Rose Tint My World.”

|

| Columbia, Rocky, Janet and Brad have all reawakened in Frank-N-Furter’s gender-bending image for the floor show. |

As Frank-N-Furter

begins “Don’t Dream It, Be It,” he asks, “Whatever happened to

Fay Wray? / That delicate satin draped frame / As it clung to her thigh, how I started to cry / Cause I wanted to be dressed just the same…” Here we see him stripped of his over-exaggerated power as he indicates that he struggled with gender, presumably when he was young. He’s been searching for how and where he fits, and “absolute pleasure” and “sins of the flesh” have been where he looked for fulfillment.

Frank-N-Furter jumps into an on-stage pool, and shot from above he’s floating on a life saver between God and man in Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. The religious imagery present in the opening scenes is re-visited here, inviting the audience to consider the juxtaposition of “giving in to absolute pleasure” and the church, which is the very institution that dictates much of what we consider gender and sexual norms.

|

| Frank-N-Furter floats in the pool, meticulously placed above Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam. |

Janet, Brad, Rocky and Columbia all jump into the pool, and as they lustfully

sing “Don’t dream it, be it,” there is a wet conglomeration of fishnets, limbs, tongues and strokes in the pool over the image of the Creation. Janet breathlessly sings, “God bless Lili St. Cyr.” She’s embracing her newfound sexuality by

referencing a burlesque dancer/stripper/lingerie designer from the 1940s and 50s.

In the midst of this dream-like pseudo-orgy, Magenta and Riff Raff violently storm into the room. Dressed in other-worldly attire (yet gender-neutral), Riff Raff is holding a pitchfork-like weapon (American Gothic, of course), and threatens Frank-N-Furter and the group. “Your lifestyle is too extreme,” Riff Raff scolds, and says he’s subverting the power and will now be the master. For all of this time, Riff Raff and Magenta have been the “help,” and saw the need for an uprising. This also supports the subversive power roles within the film. Also worth noting is that Riff Raff and Magenta are lovers and brother and sister (the American Gothic painting is said to feature a brother and sister or father and daughter, not a husband and wife like many viewers imagine). Relationships, and our expectations and discomfort levels throughout, are meant to be examined.

|

| Riff Raff and Magenta appear again as a futuristic American Gothic; his laser pitchfork will kill those whose “lifestyle” is too extreme. |

Riff Raff proceeds to kill Columbia and Frank-N-Furter with his laser pitchfork. Rocky is more difficult to kill, and while he cries and mourns over Frank-N-Furter, he throws him on his back and tries to climb the RKO radio tower on stage. Frank-N-Furter so badly wanted to feel like Fay Wray in his life, and he finally got to after he died. However, Rocky’s plan doesn’t work and the two fall backward into the pool, buried in the very source of life.

The midwestern, puritanical values that American Gothic seems to represent so well win at the end of the film, and quite literally kill difference and sexual and gender subversion. While Riff Raff and Magenta go back to their home planet Transsexual, in the galaxy of Transylvania, Brad, Janet and Dr. Scott are left on the cold ground, crawling and writhing in their fishnets.

The narrator closes the film with the

words: “And crawling, on the planet’s face, some insects, called the human race. Lost in time, and lost in space… and meaning.”

We are, the narrator suggests, quite meaningless in our earthly struggles. We blindly grasp on to expectations and norms, whether it be social constructs, gender or sexuality, and if we wander outside of those norms it will very well ruin us because of the deeply ingrained expectations we have in regard to these issues of morality.

Of course, we aren’t supposed to walk away from a midnight showing of

The Rocky Horror Picture Show feeling utterly meaningless. O’Brien himself self-identifies as transgender, and has been outspoken about how society should not “dictate” gender roles. He said in a recent

interview, “If society allowed you to grow up feeling it was normal to be what you are, there wouldn’t be a problem. I don’t think the term ‘transvestite’ or ‘transsexual’ would exist: you’d just be another human being.” He also has

said, in terms of

Rocky Horror’s significance, “Well in our western world, England, Australia and the United States etc, there are still strongholds of dinosaur thinking. But, you know, I am a trans myself and I know it’s easier for me now. I can be wherever I want, whatever I want and however I want. And I suppose to some extent, a very small extent, my attitudes in

Rocky Horror have helped make the climate a little warmer for people who have been marginalised, so that’s definitely not a bad thing.”

No it’s not. And for all its campy fun, great music and dance moves (and how ironic that the Time Warp lives on at wedding receptions across America), The Rocky Horror Picture Show also provides forceful commentary on religion, gender roles, sexual agency, control and the foreboding power that the pitchfork of puritanism holds over us all still.