This guest post written by Jessica Quiroli appears as part of our theme week on Ladies of the 1980s.

9 to 5

If I may, this is the greatest women’s comedy of all-time. So perfect on every level, it’s hard to know where to begin; but how about with the three main characters? These are women on the verge: Judy, a woman in the middle of a painful divorce, is a bundle of raw nerves and professional inexperience. Rosalee is boss Franklin Hart’s secretary, experiencing his sexual harassment on a regular basis that she dutifully smiles through, while also putting a firm foot down. She’s also misjudged by women in the office about her relationship with Hart. Her story shows a side of women in the workplace that was too often kept secret, when women couldn’t freely report their superiors’ behavior without risking unemployment. And then there’s Violet, the woman who trained Mr. Hart, and is now his “right hand.” She’s so in control, so sharp, that it only makes sense that she’s who accidentally sends them into a madcap adventure of unintentional crime. Played by Jane Fonda, Dolly Parton, and Lilly Tomlin, this wild ride is a classic in any era, but a rare, feminist gem of the 80’s.

Bechdel Test Check: Of course! It’s a comedy about working women, workplace sexual harassment, fair pay, and a good old crime caper they alone must solve. First, they discuss matters of business, lamenting Mr. Hart’s horrible sexism and incompetence; then they band together to get out of hot water. They talk survival in the first half, then literal survival, and avoiding prison, in the second half. These women have a lot more to discuss than romance.

Private Benjamin

One of the best, if just for the ending alone. Goldie Hawn stars in this unique story about a young woman, Judy Benjamin, who seeks a challenge to her otherwise nice life by joining the U.S. Army. She quickly realizes the reality of that decision, but forges ahead. Judy rises to the challenge, bonds with the other women, and eventually has to decide what life she’d rather live. The other awesome thing about this movie: Hawn co-produced it with Nancy Meyers, who also wrote the screenplay.

Bechdel Test Check: Many conversations with the awesome Eileen Brennan, who plays Captain Doreen Lewis, including on arrival, when Judy explains she’s looking for the Army with “the condos.”

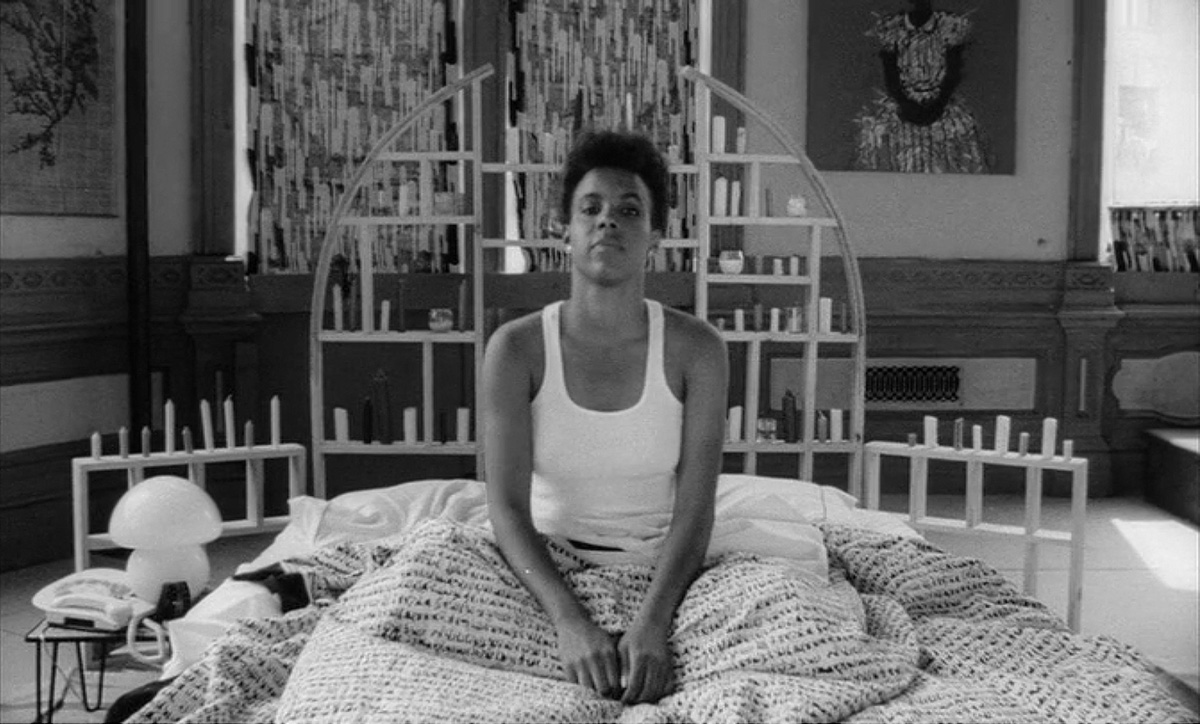

Desperately Seeking Susan

A buddy comedy without the buddies meeting until the very end. Susan, (pitch-perfect Madonna), is the exciting, perhaps dangerous woman leading an unapologetically carefree life. Rosanna Arquette’s Roberta is a woman married to a man she’s dissatisfied with, living a life she’s uninspired by. Reading about Susan’s life via a personal ads chain sparks Roberta’s imagination and she begins to follow Susan. All the action revolves around them; the men in their lives are the baffled bystanders. The women create the action, tension, and fun. Ultimately, we get two (!) heroines who’ve succeeded in the world by pursuing individual happiness they’ve refused to sacrifice.

Bechdel Test Check: Susan and friend Crystal discuss the working life. Crystal has a great monologue about feeling disrespected and being “legally blind.” Susan and Roberta’s sister-in-law Leslie chat, with Roberta’s husband Gary in the mix, about Roberta’s diary and how little they really know about her.

Fast Times at Ridgemont High

Stacy Hamilton isn’t waiting for the boys to find her. The high school girl Stacy, played by Jennifer Jason Leigh, embarks on a sexual awakening of her own design. She’s unsure, of course, but that doesn’t stop her. Stacy’s on a personal mission to achieve a rite of passage, a high school senior who’s sexually curious. She seeks advice from her experienced friend Linda (Phoebe Cates), hoping for tips and confidence. This movie’s viewed as a sex comedy for teenagers, but the subject matter’s depth, and how it’s portrayed, gives the film an emotional center with a genuinely sensitive, sometimes sad element. Yes, Jeff Spicolli, famously played by Sean Penn, is likely the most memorable character in most people’s minds (even IMDB lists him as the top billed-star). Stacy, however, is the heart and soul of the story. Her character is one we don’t see often enough: a teenage girl, discovering sex, sexual politics, and her own resolve to grow up and treat herself better.

Bechdel Test Check: There’s really nothing. If she’s talking to another girl, it’s about sex with boys.

Working Girl

Tess McGill’s devotion to her career is motivated by her desire to prove her self-worth, to no one else but herself, then to the corporate world. She has ideas, and plenty of intelligence and creativity to realize them. But her boss, Katherine (played by Sigourney Weaver) isn’t interested in helping her climb the ladder. The premise of a woman not wanting to help another woman is unfortunate, but realistically speaks to an earlier time in corporate America when it was even harder for women to succeed. Tess is fair, energetic, ambitious, and sexy. She doesn’t sacrifice anything to be loved, accepted, and successful. It’s inspiring and so fun to watch her emerge.

Bechdel Test Check: Tess and best friend Cyn, played by Joan Cusack with the most Brooklyn accent you’ve ever heard this side of a Joe Pesci movie, discuss Katherine’s absence and business meetings. Also, toward the end, Tess calls her friends and colleagues to make a huge professional announcement.

Baby Boom

J.C. Wyatt’s clocked countless hours, challenging the male-dominated corporate world so relentlessly, she’s nicknamed “The Tiger Lady.” She’s close to being made partner when baby Elizabeth comes along, after a cousin leaves her to J.C. for reasons that baffle her. Her colleagues and boss begin treating her differently. And the man she’s in a relationship with (played by everyone’s favorite, Harold Ramis) politely opts out. J.C. eventually takes her baby and business sense to Vermont and due to a dose of cabin fever, she creates a lucrative baby food company called “Country Baby.” The natural baby food achieves national success and her old company comes crawling back to her. J.C. also meets a veterinarian played sweetly and seductively by Sam Shepard, who respects her as she is, loves her, and loves her child. The story isn’t run-of-the-mill, but women everywhere can relate to juggling all the plates.

Bechdel Test Check: Really only one and it involves discussion about Elizabeth, just not a man. When Elizabeth is handed over to her by the woman from the adoption agency, Diane Keaton hilariously stumbles from impatient, to confused, to stunned, becoming completely unhinged by the circumstances.

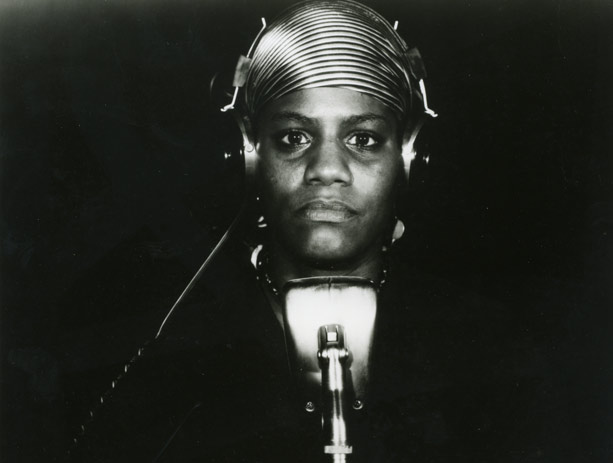

Broadcast News

This powerful comedy/drama about a female news reporter, starring Holly Hunter, is perfectly imperfect. The story, the characters, the choices, and the ending are raw reality, rather than the gift-wrapped stories Hollywood, and audiences, love. Of course we love them! But we also love the messy, relatable truth. Jane’s a highly-respected news-producer, handling the egos of news-men Albert Brooks and William Hurt, who compete professionally, and for her affections.

Bechdel Test: Joan Cusack again! Very, very briefly, Jane and Blair exchange words about a segment that needs editing. Cue the most famous scene in the movie.

Heartburn

There’s no way to omit a woman’s story that’s both legendary in literary and journalistic circles, and one relatable to many women. While many of us are merely observers of what it was like for female professionals in the 80’s (and 90’s) who were trying to balance family and career, writer Nora Ephron lived through all the societal stages. But this is a very personal story, with some really raw ugly stuff that you can easily judge, but are better off staying out of the way of, as Rachel Samstatt’s (played by freaking perfect Meryl Streep) friends and colleagues learn. Food writer Rachel has such intense doubt on the day of her wedding to Mark Foreman (played also horribly perfect by Jack Nicholson) that her friends and family, and finally Mark, have to convince her to marry him. There’s a lot to laugh at, and a lot to boil the blood, as we watch Rachel figure out who she is and what she needs to be happy.

Bechdel Test Check: One absolutely killer scene. Rachel returns to New York, after leaving Mark, and she runs into an old friend named Judith (played by Doctor Marsha from ‘Sleepless in Seattle’!). Rather than tell Judith about her husband’s affair, Rachel lies and says that her mother died. Judith tells her that she’s learned that the death of one’s mother can actually be “a blessing.” There are worse things, Judith tells Rachel. “I know, Judith. I know.”

Beaches

This is a love story between two lifelong friends. There’s no replacing the relationship, as C.C. Bloom (Bette Midler) tries explaining to husband John, played by the underrated John Heard. That might be because the friendship began when she and Hillary Whitney (Barbara Hershey) meet in early adolescence, before boys, before adult life pulls them in many directions. They’re each other’s foundation, the one thing that they can count on. Hershey plays Hillary so understated in the light of Midler’s raw, over-the-top performance, that when she falls apart, her meltdowns resonate. When they finally meet again as adults, Hillary flips a switch for a minute, announcing she’s “Free at last!,” prompting C.C. to recoil, uncertain about a person she knows to her core, but is getting to know in a whole new way. This ranks high in all-time great female friendship movies, because, mostly, they aren’t competing for a man’s attention. They’re most hopeful to receive each other’s love and acceptance.

Bechdel Test Check: Their first meeting is as young girls, but we sure need more of those girlhood stories. C.C introduces herself, as if in Technicolor, to the refined Hillary. A lot is revealed quickly about what these girls know, want, and need. Hillary hangs her head sadly, and in hardened monotone, explains that her mother died when she was a little girl. C.C. proudly announces she’s a singer, disappointed that Hillary hasn’t heard of her. C.C. also smokes, calls her mother by her first name, and attempts to calm her mother’s emotions. Hillary talks about her aunt and her concerns that she’s getting into trouble. In a sense, they’re already business women trying to meet their families’ expectations. They harbor too much responsibility, and they talk like the old friends they’ll become. In a later, pivotal confrontation they argue about envying each other.

Terms of Endearment

Essentially about two women obsessed with each other, Aurora Greenway and her daughter Emma spend their lives loving, fearing and fighting each other. Men are in their orbit, flying as close as they can, never fully understanding or appreciating them. The mother and daughter (played by Shirley MacLaine and Debra Winger) love one another in an indescribable way, and determine their purpose and happiness. They take what they can and they own it, unapologetically. When Emma begins her affair with Sam (John Lithgow) she proceeds simply and fearlessly. When Aurora talks about sex and stringing men along, or becoming a grandmother (more accurately yells like she’s been wounded), she’s confronting uniquely female experiences. Full disclosure, Emma Greenway Horton is my all-time favorite female fictional character. Created in the Larry McMurtry lab, she’s first introduced in early books as a background character. This story, in case you don’t know, ends badly. But, until then, you’ll be laughing a lot.

Bechdel Test Check: Emma’s best friend Patsy takes her to lunch with her sophisticated New York friends. After lunch, Patsy admits she told them about Emma’s illness and they argue. Later, Patsy tells Emma why their friendship is so meaningful to her.

Jessica Quiroli is a minor league baseball writer for Baseball Prospectus and the creator of Heels on the Field: A MiLB Blog. She’s also written extensively about domestic violence in baseball. She’s a DV survivor. You can follow her on Twitter @heelsonthefield.