This repost by Ren Jender appears as part of our theme week on The Female Gaze.

Nice girls aren’t supposed to walk alone in the dark, even in the movies. So in the generically titled A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night, the debut feature from writer-director Ana Lily Amirpour, we in the audience wonder what a woman in a black cloak (a traditional Iranian garment called a chador) is doing on the streets of a largely empty desert town in the wee hours. We see her witness a pimp (Dominic Rains) exploit and then cheat a sex worker (Mozhan Marnò). We soon find out the woman in the chador, The Girl–we never find out her name (played, unforgettably, by Sheila Vand) is no ordinary woman, but a vampire with fangs that retract like a cat’s claws–or a switchblade.

The film takes place in a parallel California which contains a Farsi-speaking, Iranian enclave called “Bad City.” We know we’re not in Iran because the pimp has visible tattoos and later we see a woman in public with her hair and much of her body uncovered. Also The Girl wears her chador in such a way that we see her hipster, stripey, boat shirt (too short for modest dress) and skinny jeans underneath.

In spite of its surface differences, the film to which Girl has the greatest parallel is probably David Lynch’s Eraserhead. Like that film, every sumptuous, black and white shot is framed and lit with care, creating an alternate universe for the audience to lose themselves in. And as in Eraserhead, even what we hear is fussed over in a way that grabs our attention: incidental sounds are recorded close. The proximity doesn’t alienate us, the way less skillful dubbing in other films often does, but gives us a heightened sense of intimacy, as if we are almost touching the characters.

When The Girl interrogates The Street Urchin (a young boy played by Milad Eghbali) the film shows a truth that many films, including horror films, elide–but that the other recent acclaimed horror film directed by a woman, The Babadook, also addresses–the first person who scares us when we are children is often a woman, whether it’s a mother or another woman authority figure. Tilda Swinton has said that her character in Snowpiercer was based on a particularly terrifying nanny from her own childhood. Few lines in films this year have been more chilling than the one The Girl leaves The Street Urchin with after she threatens him: “Be a good boy.”

Like Michael Almereyda, who, in the ’90s made a stylish black and white film about a woman vampire among New York hipsters, Nadja (its star, Elina Löwensohn, had eyes you couldn’t look away from, much like Vand’s) Amirpour combines familiar elements in an unfamiliar way for maximum resonance. In Almereyda’s modern day New York Hamlet (from 2000), he famously incorporated a video of Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh talking about “being” in the background of a scene, priming us to later hear Hamlet’s most famous soliloquy.

In Girl Amirpour gets at how women in modest Muslim dress (including those from Iran) are used for xenophobic and anti-Islamic fear-mongering (often in the guise of “feminism”) in the US (like in the recent ad campaign for Homeland) but also uses a chador’s resemblance to a cape to give us an eerily familiar–but new–“Dracula” silhouette. When The Girl rides on the skateboard The Street Urchin leaves behind (after he runs away from her in terror) the chador billows around her as she rolls down the road, and she becomes, without CGI trickery, a bat in flight.

Americans often read chador on women to mean vulnerability, but like the frail-seeming, pale, young, blonde Mae in another beautifully-shot, vampire Western (also directed by a woman, the pre-Hurt Locker Kathryn Bigelow) 1987’s Near Dark, who, when her cowboy boyfriend lassoes her as a “joke” takes hold of the rope and pulls him in, The Girl has hidden reserves of strength. The Girl becomes an avenging angel in black, attacking the men we see abuse women, using her “traditional” quiet passivity to draw these guys close. As the abusive men do with the cat who is many times in the frame (rarely has a filmmaker caught how much of our daily lives our animals witness) they ascribe motivations and personas to The Girl which are more about their own perceptions than about who she is or what she is thinking.

Like a number of films Girl has an early scene, fast becoming a campy cliché, in which a woman suggestively sucks the finger of a man. But when The Girl takes the pimp’s forefinger into her mouth, he gets more than he bargained for.

And as we do with Mae, we see that The Girl is lonely, and a hapless, good-looking guy, Arash, played by Arash Marandi touches something in her. When they meet, he’s coming from a costume party where he’s taken some of the club drugs he was dealing and is still wearing a vampire cape as he stares into a street light. She immediately becomes protective of him.

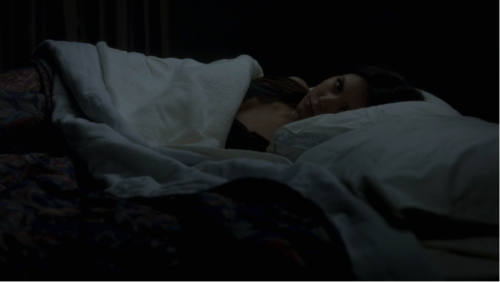

Vand’s presence burns through the screen. She has the intensity of the great silent actresses–and in many of her scenes, the ones in her room plastered with ’80s music posters, dancing by herself to Farsi synth-pop records or even when she interacts with other characters, she often does not speak. This film is low on back story but Vand’s face, especially her huge dark eyes (we see her put on her heavy eyeliner in the bathroom mirror before she goes out) tells us what she is feeling in every scene.

Amirpour’s camera (the magnificent cinematography is by Lyle Vincent) lingers over Arash’s beauty–his high cheekbones and large, long-lashed eyes under a dark, curly version of James Dean’s pompadour–in a way few male filmmakers would. His clothes (a plain white t-shirt and jeans that hug his muscled body) also evoke Dean’s. And even though the pimp, Saeed, is a villain, meant to repel us, Amirpour lets us take in the attractiveness of his body, especially in a shirtless scene with The Girl when his pants hang very low and we see the full extent of his tattoos–and his muscles.

LA has enough Iranian-Americans in it that some have nicknamed it “Tehrangeles” (after Iran’s capital), but I can’t think of another film produced near there (Girl was actually filmed in Bakersfield) in which most (or all) of the cast is of Persian descent, but no one is a terrorist or a relic from the old country. These characters speak Farsi to each other but, except for Arash’s father, with his drug addiction and collection of pre-revolutionary framed photos of family (complete with 60s-style teased hair on the women), these people aren’t living in the past–even The Girl’s retro record collection, clothes and bobbed hair reflect present-day fashion.

We can never know for sure, but just as with Black actress Gugu Mbatha-Raw giving two terrific, completely different star-turns in movies in one year but the media still largely ignoring her, I wonder if Amirpour’s flawless visual sense, skill with actors and unique reworking of a genre many of us thought didn’t have an original angle left would garner more attention if she were a white guy. Girl is distributed in partnership with VICE‘s film arm and has even made some year-end, top-10 lists, but I had to go to New York to see it and whole countries (like Canada) have yet to get even limited distribution. Nevertheless Amirpour continues to work on films unimpeded. Her next work is about cannibals. I can’t wait until its release.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_YGmTdo3vuY” iv_load_policy=”3″]

___________________________________________________

Ren Jender is a queer writer-performer/producer putting a film together. Her writing. besides appearing every week on Bitch Flicks, has also been published in The Toast, RH Reality Check, xoJane and the Feminist Wire. You can follow her on Twitter @renjender