This guest post by Amanda Civitello and Rebecca Bennett appears as part of our theme week on Cult Films and B Movies.

The Hunger, the 1983 art-house vampire flick by director Tony Scott, is perhaps the definition of “cult film,” with its plot, characterization, soundtrack, and costuming skirting the line between camp and Art. It might not be an especially good movie, despite its all-star cast – Catherine Deneuve stars as the immortal vampire, Miriam; David Bowie plays her centuries-old lover John; Susan Sarandon stars as Sarah, a scientific researcher who becomes Miriam’s new love interest – but it’s frequently beautiful and grotesque, often at the same time. It is, after all, a lavish vampire movie whose vampires are educated, cultured, and well-traveled, but definitely not “vegetarian.” Miriam and John live in a luxurious New York City townhouse decorated with antiquities that serve as a kind of timeline of her existence; she, after all, is an ancient Egyptian. John is a far more recent development (the 18th century) in her life, for the curse of Miriam’s existence is that those whom she turns enjoy an extraordinarily long lifespan, but are not immortal. Over the course of the film, we realize that John’s accelerated aging has put Miriam on the search for a new lover, so that she will not be alone when he finally expires. Dr. Sarah Roberts, a gerontologist, enters Miriam’s life at the perfect time. Ultimately, The Hunger succeeds as a work of visual art but fails on its narrative: rather than engage with the ethical issues raised by ancient vampires living and hunting in contemporary New York, it often refrains from exploring these complex tensions, privileging the visual over the story, making for a rich picture whose story falls flat. For those looking for a “classy” vampire movie for Halloween, this might be it – but be warned, art-house or not, The Hunger is incredibly bloody.

[RB]: The first thing that strikes me in watching the film is the interesting juxtaposition between the contemporary (1980s) and the classical. You see this in the soundtrack, of course, but also in the costuming and the set design. The Blaylock townhouse, for example, is filled with a seeming hodgepodge of antiquities and yet its inhabitants are thoroughly modern.

[AC]: I think it makes sense to approach the film this way, because it’s most successful as an audio-visual experience; it’s far less successful as a story. Let’s start with the music, because that’s something that almost overwhelms the film itself. The soundtrack is really beautiful in its blending of classical work (Ravel, Délibes, Allegri) with the original soundtrack by Howard Blake, and the occasional contemporary popular work.

[RB]: And this is most effective when there’s more than one kind of contrast. For example, the scene in which the aging John attempts to feed is backed by upbeat hiphop but set within a vintage-looking space, with archways and pillars. Alongside the presence of the beatbox and rollerblades, there’s this fairly antique vampire attempting to murder someone for sustenance. Tony Scott reinforces and even exploits our natural tendency to compare and contrast in the way the scenes are constructed.

[AC]: And there’s the contrast between Miriam and John’s cultured daytime existence and the primal, animalistic nature of their nighttime excursions. I think the soundtrack is used really effectively to that end. Consider the love scene between Miriam and Sarah – which is largely responsible for the film’s cult status. It begins with an impromptu concert in which Miriam plays Délibes’s “The Flower Duet,” from the opera Lakmé, and then, as they go to bed, changes to a vocal performance of the duet. It’s a beautifully romantic, soft love scene, set as it is against such a heady, operatic song. And then Miriam removes the cap from her ankh pendant, and suddenly there’s blood – and through it all, the soundtrack continues with the duet.

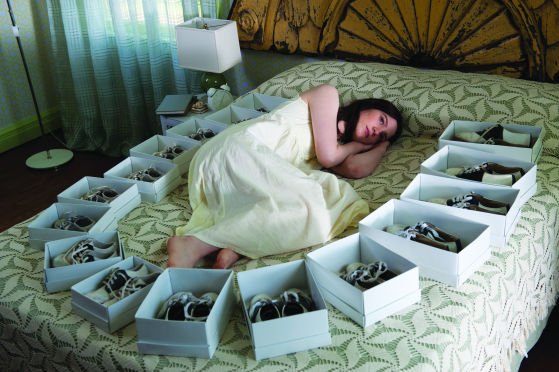

[RB]: This is also the case when John murders Alice, one of their music students. She’s playing a beautifully haunting piece of music which continues even as John slits her throat. There seems to be a persistent juxtaposition of the horrific and bloody against the beautiful, such as during the love scene between Sarah and Miriam. The movie’s costuming is similarly effective. As well as simply serving to emphasise just how divine Deneuve truly is, there’s something of a vintage feel to her clothing which reiterates what we already know about her character—that Miriam is a centuries old vampire. I think it’s worth comparing Miriam and Sarah to make this distinction. Sarah is consistently dressed in distinctly modern clothes—androgynous suits and cotton t-shirts. Miriam, on the other hand, though hardly decked out in the eighteenth century garb we see in the flashback to the beginning of Miriam and John’s time together, seems to be somewhat inspired by the elegance of the 1940s.

[AC]: The Hunger is one of those films in which Deneuve was exclusively dressed by Yves Saint Laurent (another is Indochine). Sarandon was not. There’s such a contrast in the design and aesthetics of their clothes; using YSL sets Deneuve apart from everyone else, who wear whatever the wardrobe department rustled up. Miriam’s distinctive look – a big part of what Sarandon’s character deems “European” – is in large part the YSL look. YSL is for the modern, classically elegant, powerful woman – and I think that’s basically Miriam’s character, in a nutshell. That’s important when you’ve got Miriam, dressed to the nines in YSL suits and veiled hats, prowling a nightclub for unsuspecting people to murder. Because she’s wearing clothes that are identifiably YSL – and that don’t exist as “costumes” – the film is able to reinforce that contrast between Miriam’s refinement and animalism while emphasizing her modernity. She might be a glam vampire, but she’s not an Elizabethan caricature.

[RB]: You learn something new every day! YSL or not, I do still think that Miriam’s costumes serve to emphasise the fact her “otherness” for lack of a better word, as well as the rather dangerous brand of elegance and sensuality which draws people like John and Sarah into her web.

[AC]: I think the film encapsulates that attraction really well, but is confusing on other points. I haven’t read the novel (or its subsequent sequels), but I think part of the reason why the story fails is because it doesn’t elaborate on the novel’s ideas about the nature of vampirism, which takes a sci-fi approach. In the novel, Miriam wasn’t ever human; she’s a different kind of species that resists aging and is very hard to kill. She learns that she can transfer some of her traits, like an extended lifespan, to a lover by sharing blood. This explains why her lovers can’t be turned completely, and why they hover as empty shells. The central premise of the film doesn’t really make sense without this justification. If you approach the film with more traditional vampire lore in mind, you’re searching for a reasonable explanation for why the lovers she turns don’t turn all the way – and moreover, you have to try to work out how Miriam managed to get the way she is. The novel’s reasoning makes far more sense.

[RB]: Perhaps for the movie’s purposes, that doesn’t matter: the story seems to be far more driven by the desire to create an artistic film, rather than an intellectually/ethically/

[AC]: One thing that I really wish the film had actually addressed is the tension of Miriam’s existence. We know that the fact that she’s condemned a parade of lovers to a miserable half-life, locked away in steel coffins but still “conscious,” tortures her. She actively looks to science to extend John’s life by following Sarah’s research; when it becomes apparent that he has declined beyond all hope, she mourns. And yet, she still turns her attention to someone new. Why?

[RB]: I suppose as distraught as Miriam might be by the loss of John and her many other lovers, loneliness would be worse. She loves her companions, but it would be worse to exist alone rather than remain faithful to the memory of what they once were and mourn perpetually. Or perhaps it simply serves to drive the narrative forward!

[AC]: And what does that say about her as a character? On the one hand, while it isn’t anything new to see a female villain, Miriam has a conscience. It’s almost as if she can’t help herself.

[RB]: I think it’s significant that she’s motivated by that fear of loneliness. After all, her former lovers are all trapped in those steel coffins because she cannot bear to kill them and end their suffering. It’s incredibly selfish – as is her plan to turn Sarah – but incredibly sad as well.

[AC]: I have to say, I really despise the ending (in which her former lovers extract their revenge on Miriam, helping Sarah to make Miriam like them), because it doesn’t make sense. In the DVD commentary, Sarandon says, “All the rules that we’d spent the entire film delineating, that Miriam lived forever and was indestructible, and all the people that she transformed [eventually] died, and that I killed myself rather than be an addict [were ignored]. Suddenly I was kind of living, she was kind of half dying… Nobody knew what was going on, and I thought that was a shame.” And I think she’s right. Beyond being implausible in a narrative sense, the ending basically rewrites everything we’ve come to know about Sarah. I think it would have been a more satisfying end to the film to have seen Miriam in London, alone at her piano or, alternatively, with a new lover. It would have been a far more powerful statement for Sarah to have killed herself, and for the final scenes to show Miriam facing the prospect of eternity alone.

Amanda Civitello and Rebecca Bennett are the two halves of a very happy couple who became close while collaborating on this review of Sleepy Hollow, which probably makes them the first Bitch Flicks couple. Together they founded and edit Iris | New Fiction, a new, nonprofit literary magazine of fiction, poetry, and visual art for LGBTQ+ teens and their allies. Catch up with Amanda at her site and twitter, and say hi to Rebecca on twitter.