Characters with physical or developmental disabilities are rarely given prominent roles on television ensembles, much less well-developed characters. Glee and American Horror Story, TV shows created by Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk, both feature important characters with Down Syndrome and have received much praise for it. Glee’s Becky Jackson and AHS’s Adelaide Langdon and Nan are all portrayed as flawed women and are allowed their own inner lives, desires, and triumphs.

However, the mere existence of these characters is not enough to suggest they are well portrayed and in each character there are several questionable areas that warrant discussion. Though one must take this criticism with a grain of salt, as Glee is a surreal over-the-top comedy where everyone is made fun of to a degree (though has been consistently problematic in its portrayal of women, the disabled, bisexuality and transwomen, among others) while American Horror Story is literally a horror show, where nearly everyone suffers and dies and indulges in many horror movie cliches–among them the child-like prophet and the martyr.

Becky

Becky Jackson (Lauren Potter) was introduced in Glee’s first season to as a means to character development for the show’s previously one-dimensional villain, Sue Sylvester. She was a shy, young girl with Down Syndrome, a social outcast who just wanted to be a cheerleader.

When Sue put her through a rigorous audition process, viewers and Glee Club leader Will Schuester assumed this was yet another of Sue’s cruelties. Obviously Sue was just torturing this girl for her own amusement with no hope of her actually making the squad, but this assumption was proved wrong when the show revealed that she reminds Sue of her sister Jean, who also has Downs.

Sue tells Will she is treating Becky just like everyone else because that’s what she wants and from then on Becky is a Cheerio, Sue’s constant sidekick and assistant and frequently recurring character.

Becky also continues to aid in the development of Sue’s character, as she becomes her voice of reason, being the the only one who can criticize Sue’ behaviour and talk to her on her level without fear of retaliation. For example, when Becky learns that Sue’s baby will likely have Downs, she is able to tell Sue that she needs to work on her patience to be a good parent. Becky functions as Sue’s heart and when Sue is shattered by her sister’s death, she expresses her grief by casting aside the only other thing that made her human, and kicks Becky off the Cheerios. Their bond is restored when Sue welcomes Becky back to the squad and promotes her to captain, after realizing how much it helps her to have Becky in her life.

However, for Becky, her relationship with Sue results in the loss of her own personhood. In a relatively short length of time, Becky gives up any other interests or ambitions she had and becomes a miniature version of her hero, Sue (even dressing her for Halloween). For most of the show, Becky is Sue’s mouthpiece, echoing her criticisms and opinions and making snarky and frequently offensive comments in the same manner that Sue is known for. She even shares Sue’s grossly inflated sense of self worth and importance (Helen Mirren is her inner voice) and heckles and sabotages other students when given the opportunity.

For brief period, it was fun that Becky could be as mean and snarky as almost all the other characters, but as the show dragged this on to become Becky’s defining characteristic, it become patronizing and unfunny. Becky is not portrayed as an otherwise ordinary teenage girl with interests in sex and blue humour but as low comedy, like a child swearing. The joke wasn’t what she was saying but that she was saying these kind of things at all.

In addition, Becky is constantly prepositioning other characters and making crude sexual comments about them. She lusts over the Glee Club’s Men of McKinley calendar and claims ownership of one-time date, Artie Abrams when she sees him kissing his girlfriend, calling him her future husband. However, none of her attractions are treated as valid. When she pays for a kiss at a kissing booth run by quarterback Finn Hudson, he kisses her on the cheek; when she and Artie bond over their disabilities on their date, he breaks up with her after she asks him to “do it” with her (in an alternate reality where Artie never went out with her, Becky became “the school slut”); and when she seems to find happiness with Jason, who also has Down Syndrome, she claims the relationship couldn’t work because he liked hot dogs and she liked pizza. By hypersexualizing a character who is treated as humourous for having a sexual desire and never considered as a viable romantic option, she is also desexualized and infantilized, treated like a child who doesn’t understand that (from the narrative’s perspective) the conventionally attractive characters aren’t interested in sleeping with her and she’ll never be prom queen.

There have been two particularly problematic plot lines featuring Becky in Glee’s recent seasons, both which could be essays in their own right. In season four’s much-maligned Shooting Star , Becky brings a gun to school because she fears the world outside the safe bubble of McKinley High, suggesting individuals with Down Syndrome are unstable and dangerous. In season five episode, Movin’ Out, frequent misogynist Artie decides to “save” Becky and helps her find a college with programs for people with developmental disabilities, something she hadn’t considered previously. While this recent story has a positive message about Becky’s future and her abilities, the fact that another character, one who she stalked after he rejected her, imbues it with the same patronizing dynamic found in much of the plot lines featuring Becky.

Adelaide

The first episode of American Horror Story: Murder House opens in 1978 with Adelaide Langdon, a young girl with Downs ominously warning two boys they will die if they go into the titular house. In the next scene, her warning comes true.

As an adult over 30 years later, Adelaide (Jamie Brewer) continues to given warnings, frightening the Harmon family who have just moved into the house, next door to where she lives with her mother Constance (Jessica Lange). Though she is well meaning and friendly, her warnings are constantly misconstrued as threats due to her creepy habit of starring unblinking and appearing out of nowhere in the Harmon house.

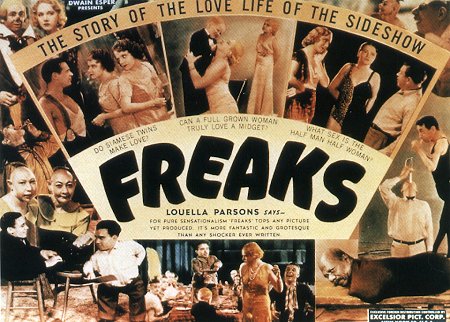

Being a character on a horror television show, Addy’s Down Syndrome is used to frame her as an uncanny figure, an other in the style of Tod Browning’s Freaks. In horror or gothic media, the uncanny is something that is familiar, yet strange at the same time, producing an unsettling and comfortable feeling, such as identical twins, mutes or people with developmental disabilities. Seemingly, Addy is able to enter the house whenever she desires, no matter what barriers are in her way, suggesting a magical, otherworldly aspect of her character. Her Down Syndrome alone is meant to produce discomfort in the viewer, manipulating them into wondering if she is evil or will, even unthinkingly, harm the family, for no other reason than that she is so othered.

Raised to believe she is an ugly monster who should keep out of sight, Addy wants nothing more than to be “a pretty girl” and mourns that she doesn’t look like the women in her fashion magazines. Her mother frequently insults her, calling her a burden and a ‘mongoloid’ and reinforcing over and over that Addy’s dream will never happen. Cruelly, Constance punishes her by locking her in the “Bad Girl Room,” a closet full of mirrors, further reinforcing Addy’s monstrous self-image.

Addy’s story ends sadly on Halloween when she is hit by a car and killed. Here, the show’s treatment of Addy continues to be problematic as it tries to have it both ways, portraying her as both something to fear and as an object of pity, a tragedy for viewers to mourn. When Addy dies she is wearing “a pretty girl” Halloween mask and just minutes before, she was ecstatically happy to finally be the person she’d always wanted, even if it was only in a small, temporary way. Like Sue, Addy is also used to humanize a bigoted character, as Constance, who caused most of the problems in Addy’s life puts makeup on Addy’s corpse and cries while telling her she’s “beautiful.” This suggests that Addy’s purpose in the narrative was chiefly to facilitate Constance’s character development, rather than a storyline or a life of her own.

Nan

Unlike Adelaide, whose story is presented as a tragedy centered around her Down Syndrome, Nan’s condition is never mentioned but subtly informs how she is treated by the narrative and the other characters. A young clairvoyant on American Horror Story: Coven, Nan (Jamie Brewer) is in most ways, portrayed as a normal girl. She admires the hot neighbor with her classmates, joins in on their catty comments and using her powers for cruel, teenage girl teasing (trying to make Madison put her cigarette in her vagina) in a way that doesn’t seem like the joke is that she is saying these things at all.

Nan is however, constantly dismissed even within the group that tacitly includes her (problematically, Queenie who is Black is treated as the real outsider). She is never considered a serious contender in the season long competition to see who is the most powerful witch of her generation, the Supreme, called ugly by Queen Bee Madison and the discovery that the neighbor, Luke is interested in her is treated as unbelievable by other characters.

However, sad as it may be, this is probably be an honest portrayal of how such a character would be treated in such an environment full of bitchery and backstabbing over any character flaw or deficit in appearance. Unlike Queenie, whose difference and feelings about her exclusion from the coven’s majority of white witches are explored in detail, Nan’s feelings are glossed over. She is different, but her difference is never examined, so it becomes an elephant in the room.

Like Adelaide, Nan insists she is not a virgin when it is assumed by other characters. She says she has sex all the time and men find her hot, however because the show never gives any background on who Nan was before she came to the school (as is given for all other characters), it is not clear whether this is true. The storyline of her romance with Luke is never able to progress to a romantic or sexual relationship as he is quickly murdered by his mother so he will not reveal her secrets.

Nan is portrayed as the moral center of the school/coven as her power, allows her to see into the hearts of the people around her. She mediates in fights and threatens to tell the police about the baby Marie Laveau had kidnapped earlier. However, Nan has a dark side which is briefly explored when she uses her powers to kill Luke’s mother, by compelling her to drink bleach, as revenge for her murder of Luke.

She is ultimately murdered by matriarchs Marie and Fiona Goode, functioning bringing them closer together. Her death is used as the sacrifice of an innocent soul, but it is suggested that Nan had some choice in the matter and decides to leave the coven to destroy each other so she can be at peace. The one bad thing she does, the neighbor’s murder is excused because it was deserved and as she is accepted as an innocent, a soul too pure for this world. In this manner, Nan comes close to the stereotype of the saintly disabled person, and is portrayed as a martyr, the lone character over the season who is never resurrected.

Ultimately, though are three characters discussed here have problematic and debatable qualities, both in their personalities and in the way they are framed by their respective narratives, they offer unique portrayals of women with Down Syndrome. If nothing else, they are all prominent characters who are treated as people rather than public service announcements in major television shows. Hopefully they are seen as steps in the right direction.

Recommended Reading: Will This Depiction of Down Syndrome be a Horror Story? ; Exploring Bodily Autonomy on American Horror Story: Coven ; Glee’s Not so Gleeful Representation of Disabled Women; The Complicated Racial Politics of “American Horror Story: Coven”; Disability Advocates Call ‘Glee’ Portrayal ‘Poor Choice’

___________________________________________________________________________________

Elizabeth Kiy is a Canadian writer and freelance journalist living in Toronto, Ontario. She recently graduated from Carleton University where she majored in journalism and minored in film.