Based on the book by Roald Dahl, James and the Giant Peach has been a favorite movie of mine since childhood. After all, what kid wouldn’t love a cast of singing and dancing insects?

(Before I go into a review of the movie, I must state that I have never read the book, and do not know how closely the movie follows. Any comments I make are on the film alone, not the book.)

Directed by Henry Selick, the story revolves around a boy named James, who after the death of both parents, ends up a slave to his two cruel aunts, Sponge and Spiker. After an encounter with a strange man promising him “marvelous things,” James receives a bag of magical sprites, (crocodile tongues boiled in the skull of a dead witch for 40 days and 40 nights, the gizzard of a pig, the fingers of a young monkey, the beak of a parrot and three spoonfuls of sugar to be exact), that inadvertently end up planting themselves within a barren peach tree. An enormous peach sprouts from the tree at contact, which James later escapes into, turning into a claymation version of himself. Alongside a band of personified insects, the group sail across the ocean on the peach, encountering various trials as they head towards their destination in New York City.

The aunts, Sponge and Spiker, are two of the worst people to ever grace the silver screen, with their terrible abuse of young James setting the stage for the adventure ahead. They serve as the main antagonists of the story, chasing James across land and sea to recapture him.

The Aunts are horrific caretakers; starving, beating, and emotionally abusing James relentlessly. Mind you, this is a movie for children. And like in most children’s movies, the Aunts’ outward appearance reflects their inner evil. Both women are made to look terrifyingly cruel and yet simultaneously clown-like, dressed in orange-red wigs and slathered on make-up. During their first 20 minutes on screen, the two women participate in dozens of morally reprehensible practices, everything from shameless vanity to verbally attacking a woman and her children.

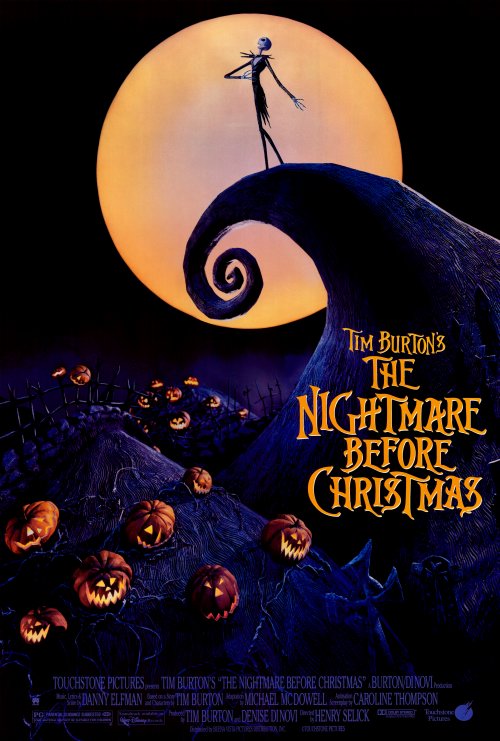

The fact that the villains are female does not bother me, nor that they are portrayed as greedy, selfish people. After all, women are just as capable as men of committing child abuse. However, while the style of the movie is very dark and Tim Burton-esque, I can’t help but wish that the Aunts’ appearances were not related to their evil. Too often in the world of children’s movies a villain need only be identified by their ugly appearance, as if that is a symptom of inner ugliness. Just look at most Disney movies from the past century!

The women’s abuse of James was also very dramatic and purposeful, most likely so that the children watching the movie could understand James’ need for immediate escape. The film could have used the Aunts as an opportunity to delve into the other types of child-abuse, but instead meant to focus on the strong atmosphere of fantastical adventure. (With a story that involves death by Rhinoceros, skeleton pirates, and mechanical sharks, it is easy to understand why the people themselves are wildly unrealistic. The world itself is wildly unrealistic.)

Transformed by the sprites themselves, James finds a group man-sized insects living within the giant peach, each with a unique personality that relates to their species. There is a smart, cultured grasshopper; a kind, nurturing ladybug; a rough-talking, comedic centipede; a neurotic, blind earthworm; a poetic, intelligent spider; and a deaf, elderly glowworm.

The spider, glowworm, and ladybug are all female, each very different and yet immensely likeable. It’s great to see several types of female personalities represented, though perhaps they are a little clichéd. Miss Spider is the typical sensual seductress, the Ladybug a doting mother-figure. The glow-worm has no real part except serving as a lantern inside the peach, and occasionally mishearing a phrase for laughs.

James: “The man said marvelous things would happen!”

Glowworm: “Did you say marvelous pigs in satin?”

Miss Spider in particular is a great female character; strong, smart, and willing to stand up for herself and those she cares about. Despite her reputation as a killer and cave-dweller, she repeatedly defends James and wards off the assumptions the other insects have made-about her. From the moment she is introduced in her personified form, you can’t help but like her. She doesn’t take anyone’s crap.

Ladybug comes off as an older, traditional woman, complete with a flowered hat and overfilled purse. She is kindly, though strict about manners and being polite. When describing what each bug hopes to find in New York City, Ladybug is most concerned with seeing flowers and children. And while Ladybug does resemble an Aunt of mine to disturbing proportions, I felt like she had no purpose in the story other than to serve as James’ replacement mother/grandmother. While the other insects are having swashbuckling adventures and near death experiences, Ladybug is just scenery, screaming and cheering in the correct places. Which is odd, because every insect has a large amount of screen time devoted to their stories and transformation, minus the glowworm and ladybug. Both female characters. In the end, it was James, Miss Spider, Centipede, Earthworm, and Grasshopper who repeatedly saved the day. Ladybug was just there to reassure James of himself whenever fear or doubt overtook him.

Despite this unfortunate exclusion, I still would highly recommend the film to anyone who is interested. It is visually stunning, undoubtedly original, and teaches a lesson about family that is quite touching.

From a feminist perspective, my favorite thing about the film is that it doesn’t pay any attention to sex at all. At no point are the Aunts’ criticized for being a disappointment to the name of maternal women. At no point is Miss Spider treated differently because she is female. No, almost every character has an inner and outer struggle, each reaching a defining moment in the plot where they must test themselves to save those they love. Together, the insects and James form a makeshift family, each working equally with one another to build a happy life in their new home. (And the boy who plays James is too cute for words, all his emotions and inner growth come off as genuine. You can’t help but cheer for him as he finally stands up to his aunts.)

Overall, James and the Giant Peach is an excellent movie, and I would suggest it to any parent or person who likes stories of adventure and fantasy. Any warnings I would give would refer only to the dark nature of the beginning of the film, and to any people who may be afraid of giant, rampaging rhinoceroses.

Libby White is a senior at the University of Tennessee, studying Marketing and Spanish full-time. Her parents were in the Navy for most of her life, so she got to see the world at a young age, and learn about cultures outside her own. Her mother in particular has had a huge influence on her, as she was a woman in the military at a time when men dominated the field. Her determination and hard-work to survive in an environment where she was not welcomed has made Libby respect the constant struggle of women today.