Written by Lisa Bolekaja, this article appears as part of our theme week on Interracial Relationships.

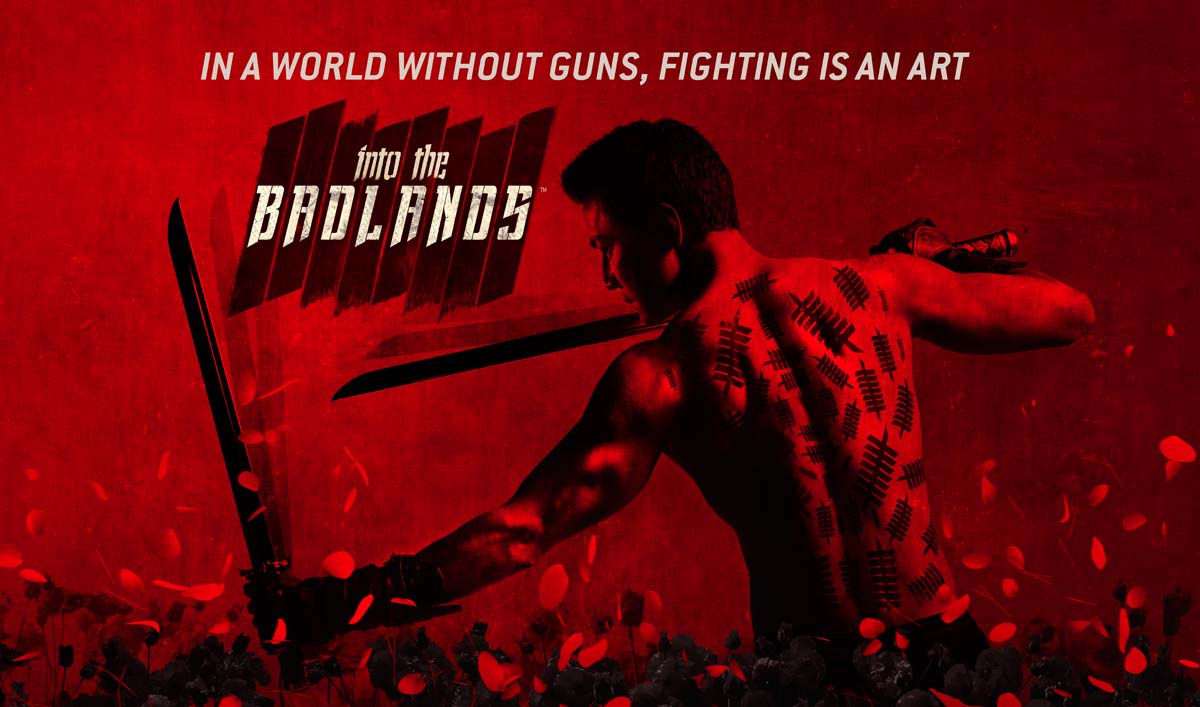

For the last few weeks, fans of AMC’s Into the Badlands have been waiting to hear if the series will be renewed for a second season. Its six-part first season story arc hooked a number of viewers who eagerly await more episodes of the dystopian, martial arts fantasy extravaganza. The show is a throwback to the action excitement of 1970s Kung Fu theater with large doses of mystery, adventure, beautifully choreographed fight sequences, and a forbidden romance at its core. I am a big fan and find myself constantly checking social media to see if I will be gifted with another season.

Into the Badlands, based on the classic Chinese tale Journey to the West, is set in a futuristic dystopian world where past wars have created a new feudal society divided up between seven “Barons” who run everything on various Louisiana plantations — harking back to images of a slave society and a brutally defined hierarchy. People pick poppy plants instead of cotton, and everyone’s clothing looks like updated Gone With the Wind duds, only cooler looking with lots of leather. Guns have been banished, and although people originally flocked to the various Barons for protection and guidance in a world turned upside down because of war, the “protection” eventually lapsed into forced servitude. There are townspeople; healers, merchants, bar owners, brothels etc., and then there is the warrior class who live on the plantations.

Under the leadership of the Barons are lethal trained killers known as Clippers. Children with the potential to become Clippers are called colts and go through military training in the martial arts. Everyone else who isn’t trained in the art of war is forced to work on the plantations growing the poppy plants that are harvested into opium. They are known as cogs. (read: slaves).

The top Clipper on any given plantation is known as a Regent, and action star Daniel Wu is Sunny, the baddest Clipper in all the Badlands. He has tattoos on his back for the number of people he has killed. Sunny’s Baron is the conniving and ruthless Quinn (Martin Csokas), a man determined to control all of the Badlands. Quinn doesn’t know that the other Barons are plotting to overthrow him, and his personal life is a hot mess (two wives who dislike each other, and a son itching to take over). He depends on Sunny’s loyalty and fighting prowess. All Clippers are beholden to and only live for their Baron. They are not allowed to marry, have children, or have personal lives outside of the Baron’s wishes. Everyone in this society lives at the discretion and bidding of the various Barons. To go against this hierarchy of power and position is to risk immediate death.

Orphaned as a child, Sunny only knows the life of a Clipper. When we first meet him, he has been dispatched on his motorcycle to check on a cargo of new cogs that have not arrived at Quinn’s plantation. Sunny finds that the cogs have been killed, their bodies still chained together and rotting on the side of a desolate road. He notices that there is a person missing from the shackled group of slaves and sets off to find Quinn’s stolen property.

This scenario sets into motion two events that change the course of Sunny’s life forever. The first event is finding and rescuing M.K. (Aramis Knight), a young teen who wears a mysterious pendant that represents a fabled city called Azra that lies outside of the Badlands. People don’t believe it exists, but Sunny recognizes the pendant as something that matches a compass he owns and has hidden away from his own childhood. Sunny is intrigued with M.K., curious to know why he was kidnapped and not murdered like the other cogs. The second event that shakes up Sunny’s life is that the forbidden romance he’s has been secretly having with Veil (Madeliene Mantock), a Black woman who works as a healer in town, has borne fruit: Veil is pregnant and she’s keeping their baby, rules be damned.

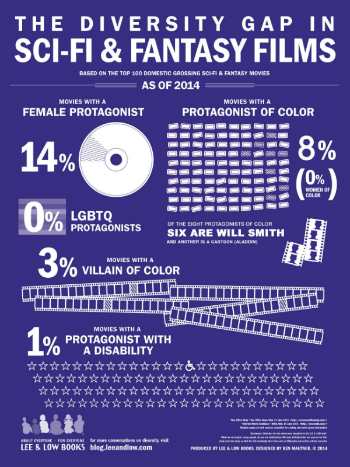

What makes Sunny’s relationship with Veil exciting to me is the fact that it is a unique interracial pairing between two people of color. And not just the usual (almost cliché) interracial pairing of a White person with a person of color that we often find in film and TV. (On the flip side, the real shocker would have been to cast a talented Asian actress as Sunny’s love interest. Two people of color from the same racial background who are in love and have a romance at the center of the narrative? What? I can only dream.)

My mouth literally flew open when the show premiered on the east coast first and I saw a picture posted on social media of Sunny and Veil in bed together. The first reaction was, “Wow an AMBW couple on TV in bed together! Blasian love!”, and immediately afterwards I thought, “Damn, should I even bother to be invested in that relationship? They are probably going to kill her in the first episode.” I was bummed that my reactions were excitement about a Black woman being loved on, and then automatically assuming that she would be killed off because it has been proven that Black characters tend to be bumped off first. It’s tradition; this assumption about Veil’s immediate demise had levels to it.

Typically, women are used to motivate male characters into action, via revenge or to have someone to rescue. They exist as plot devices (with tropes like Damsel in Distress or Women in Refrigerators) to help the story move along. This problem is exacerbated at times when that woman is a woman of color because they are not often deemed as important as a white female character. If Veil had been white, in my mind, she may last a few episodes. But because she was Black, I girded my loins and waited for the big chop. This saddens me because by the time I was able to watch the entire show during its west coast broadcast, I had already prepared myself to let Veil go. And praise ye old Gods, Veil has survived all six episodes, and actually has some agency.

The rare pairings of an Asian male character and a Black female character has a tenuous history in cinema. The few films that even touch upon the slightest hint of a possible romance between AMBW couples has been disappointing. The two most recent films that my cinema friends and I still complain about is Ninja Assassin and Romeo Must Die. There was obvious chemistry between Naomie Harris and Rain. There was even a rumored shower scene between them that was supposedly cut. But Ninja Assassin just toyed with us, and fans of the film created fanfiction to fill in the gaps of romance that may have been there more overtly had Naomie Harris’ character been a white woman.

The travesty that is Romeo Must Die has always irked fans of that film. Jet Li and the late Aaliyah couldn’t even get a kiss at the end? All that sexual tension, and flat out cuteness together didn’t warrant a little lip action? It has been said that there was a kissing scene at the end that was cut because a test audience didn’t like it. I don’t know who was in that test audience that ruined the earned love scene of Jet Li and Aaliyah, but in the words of Sam Jackson, I hope they die and burn in hell. We were robbed.

The closest thing that I’ve seen that even tried to have a recurring Blasian couple was Flashforward (2009) with John Cho and Gabrielle Union. But then Cho’s character ended up getting a lesbian white woman pregnant on purpose and…yeah, that sucked.

There are other films and TV shows that have had AMBW pairings:

Virtuality (2009)

Robot Stories (2003)

Catfish in Black Bean Sauce (1999)

Cinderella (1997)

Fakin’ Da Funk (1997)

But it’s a nice surprise to see a deeper relationship between Veil and Sunny. It would be great if we could see more of their love scenes developed. The arrival of M.K. and Veil’s pregnancy have created an urgency in Sunny that tests his loyalty as a Regent/Clipper. Some of the writing of the show has me questioning why Sunny is so loyal to the unstable, villainous Quinn. Quinn murders Veil’s adoptive parents. Sunny tells Veil what happened when she confronts him about it, and yet he still goes back to work like “I can’t do anything.” Sunny finally making plans to escape with Veil and M.K. come a little too late. We needed to see him stand up for his woman and baby sooner.

Thank goodness Veil isn’t allowed to be a weak damsel in distress waiting for Sunny to save her. She works through difficult situations to keep herself and her unborn child alive when he’s not around. Veil even tells Sunny that she may or may not leave with him once he secures passage on a boat for them to escape. It’s a small moment that lets the audience know that she will make it with or without Sunny.

Sunny and Veil are set up to be a surrogate family for M.K. and the boy is pretty quick to pick up on the fact that the secret affair of Sunny and Veil is pretty obvious whenever they are near each other. M.K. himself has the beginnings of his own interracial romance with Tilda (Ally Ioannides), the Clipper daughter of a female Baron known as The Widow (Emily Beecham — one of my favorites on the show), which brings on another set of problems that mirror Sunny and Veil’s forbidden union.

Into the Badlands is an imaginative show that is here for fans of dynamic martial arts, and also kickass women. More than half of the main cast is made up of women full of agency who drive the series just as much as the men. My only criticism in that respect is that Veil is the only regular cast member who is a woman of color. I see a lot of female background extras that are women of color, (just like there are tons of men and boys of color on the show, even those with regular speaking roles), so it would’ve been nice to see another woman of color who is a major player. It’s pretty lazy casting to have six female speaking parts, and only one is a woman of color? And no, The Widow being a redhead does not count as diversity in women. They could have given us at least three women of color. Asian, Native, Latinx…so easy to do. But no. There’s just Veil.

The season finale left us with a cliffhanger. M.K. kidnapped again, Sunny tied up on the boat and what that means for his family’s safe passage out of the Badlands, and Veil left alone in town wondering what happened to her man. The six episodes were fast and furious fun, and I hope that Sunny and Veil’s relationship continues over the long haul. It’s exciting to see a handsome Asian male actor shine as the hero, be a sexually desired hottie, and NOT be a stereotype or sidekick to a white male character. It’s also gratifying to finally get an onscreen Blasian couple where they kiss, have sex, and get to have a real relationship. At least I hope so. C’mon, AMC. Renew Into the Badlands. The fans are waiting.

Staff Writer Lisa Bolekaja is a writer, screenwriter, and podcaster. She’s an Apex Magazine slush reader, a member of the Horror Writers Association, a former Film Independent Fellow and a Twitter fiend. You can find her posted up on the AMC Into the Badlands fan page waiting for word of Season 2.