Warning: if you have not watched all of American Horror Story Season 1, there are massive spoilers ahead!

American Horror Story co-creators Ryan Murphy and Brad Falchuk wanted to create a TV series that truly scared people. And they’ve definitely succeeded in their goal. But why the hell are they so afraid of abortion and women’s reproduction?

Inspired by The Exorcist, Rosemary’s Baby and The Shining, the creepy, eerie and phenomenally acted and well-written show follows the Harmons — cellist Vivien (Connie Britton), psychiatrist Ben (Dylan McDermott) and their daughter Violet (Taissa Farmiga) — as they move from Boston to Los Angeles to heal over past traumas of a stillbirth and infidelity. They move into an old haunted mansion in this “violent, erotically charged horror story about a troubled family.”

American Horror Storysucked me in immediately. Besides passing the Bechdel Test many times, strong, clever, interesting women abound. The performances by Connie Britton, Jessica Lange, Dylan McDermott, Frances Conroy and Taissa Farmiga are outstanding.

A horror for women? Sounds promising. Ahhhh but not so fast! If the show is for women, why do we see women objectified, conflating sexualized images with rape, assault and violence. And why the hell is it obsessed with demonizing abortion and pregnancy??

In the series premiere, we first encounter Vivien in a gynecological exam (after a brutal stillbirth) and her doctor prescribes her hormones. Eco-friendly Vivien, who uses organic products and doesn’t like using anything synthetic, responds:

“I’m just trying to get control of my body again, especially after what happened.”

That line might just be the most prophetic in the series. The female characters’ bodies are continuously invaded, brutalized and dominated.

In the series premiere, Vivien is raped by the Rubber Man, thinking she’s having sex with Ben but who’s really ghost Tate. At the end of the episode, we learn Vivien’s pregnant…with twins…by two different fathers. It’s crystal clear that as soon as Vivien gets pregnant, she’s having a “mystical pregnancy” and will give birth to a demon baby. Vivien has a nightmare that she can see a hand (paw or claw??) moving underneath her swollen pregnant stomach. In “Open House,” the obstetrician tells Vivien and Ben that “every woman worries she’s got a little devil inside her.” We’re also told several times that one of Vivien’s twins is growing at an alarmingly rapid rate. Vivien eats cooked offal and later ravenously devours raw, bloody brains, paralleling the liver-eating scene in

Rosemary’s Baby. Murphy attributes this to the baby having “

demonic cravings.”Angie, the ultrasound technician, faints when conducting Vivien’s ultrasound. When she meets with Vivien later in a church, Angie tells her that she saw the devil on the sonogram, “the unclean thing, the plague of nations, the beast.”

“It’s common practice for Hollywood writers to have their female characters become pregnant at some point in their TV series. These story lines are almost always built around women who have their ovaries harvested by aliens or serve as human incubators for demon spawn – basically the characters are reduced to their biological functions.”

Sarkeesian goes on to quote Laura Shapiro who called the Mystical Pregnancy “a type of reproductive terrorism:”

“…It makes becoming pregnant seem disgusting, frightening and nightmarish…The problem from my point of view is that pregnancy and birth are natural processes that are being distorted into torture porn, ways of punishing women and exploiting their terror to up the dramatic stakes.”

After she learns of Vivien’s pregnancy, Hayden (Kate Mara), Ben’s student who he had an affair with (and who’s killed after she tells Ben she’s keeping their baby), becomes obsessed with stealing Vivien’s baby. And if one babystealer wasn’t enough, Constance and former house dwellers Nora (Lily Rabe) and Chad (Zachary Quinto) conspire to steal Vivien’s unborn baby too. Babysnatching! Cause that’s what all women and gay men do. Oh wait, that’s what all “crazy” women do…Wait, aren’t all women “crazy???” (The show’s treatment of mental illness is a topic for a WHOLE other post).

As each of these characters can’t procreate (Constance due to her age, Hayden and Nora as they’re dead, Chad a man…who’s now dead), they covet Vivien’s capacity for reproduction. They objectify Vivien, reducing her to a vessel, an incubator for the baby these characters so desperately yearn to possess.

Vivien’s pregnancy is in many ways the crux of the show. Even on the poster, a pregnant Vivien arches her back seductively as the Rubber Man hovers above with outstretched hands, as if waiting to pluck the baby from her womb.

In “Piggy Piggy,” Leah, Violet’s former bully, tells Violet the devil is real. She discloses information in the Book of Revelations from the Bible:

“In heaven, there’s this woman in labor, howling in pain. There’s a red dragon with 7 heads, waiting so he can eat her baby. But the archangel Michael, he hurls the dragon down to earth. From that moment on, the red dragon hates the woman and declares war on her and all her children. That’s us.”

In “Spooky Little Girl,” medium Billie Dean tells Constance that a child conceived by a human and a ghost (Vivien and rapist Tate) would result in the antichrist and would bring about the apocalypse. In the penultimate episode, when Vivien gives birth, scenes flash between the horrific current situation of Vivien dying — a scene inspired by the film Demon Seed — and Vivien and Ben’s joyous delivery of Violet 16 years earlier. But Vivien dies in childbirth, giving birth to one baby who lives (and who’s a murderous sociopath) and one who dies.

In fact the entire season, from the first episode to the last, revolves around Vivien and her pregnancy who inevitably becomes the allegorical “

Woman of the Apocalypse.” Hmmm, so we should all fear women because they could at any moment incite the end of the world.

According to American Horror Story, we shouldn’t just be terrorized by pregnancy. All aspects of reproduction should scare the shit out of us, including abortion.

In the title sequence for each episode, we see jars of aborted fetuses on the shelves in the basement –again fueling the fire of fear and disgust surrounding abortion. It feels like the messages implied here are “good” women don’t get abortions and abortions are gross and scary. Don’t believe me? Trust me, it gets reinforced over and over again. In fact, because of the macabre show’s obsession with abortion,

Feminist Film renames it “

American Abortion Story.”

Abortion is discussed throughout the series. Vivien and Constance (who says her “womb is cursed”) talk about abortion after Vivien worries something’s wrong with her baby. After the Harmons move to LA, Ben returns to Boston to accompany Hayden to get an abortion. We witness her emotional instability after Ben checks his phone (because you know, no one in their right mind would choose to get an abortion…eyeroll!). Then Hayden changes her mind and decides to keep the baby…which she never has since she’s murdered.

In the 3rd episode, when Vivien takes the “Eternal Darkness” house tour,” she discovers the history of the Montgomerys and Charles’ “Frankenstein complex.” In 1922, surgeon Charles Montgomery and his socialite wife Nora lived in the house. When they need more money to pay their bills, Nora arranges for Charles to perform illegal abortions on young women.

The “Eternally Damned” tour guide also condemns the Montgomerys’ performing abortions: “But the souls of the little ones must have weighed heavy upon them as their reign of terror climaxed in the shocking finale in 1926.” Reign of terror? Is that what you call abortions?? At first I thought I must have missed something…perhaps the girls were being murdered. But nope. The abortions are the “reign of terror.” Lovely.

As

Tami at What Tami Said astutely points out, the inception of the house’s evil, its pull in harboring pain, despair and tortured souls, all stems from one person: an abortionist. Oh and to hammer home the point that abortion equates to evil, the episode is entitled “Murder House.”

In another episode, we learn in a flashback that one of the women’s boyfriends, angered by her abortion, kidnaps Nora and Charles’ baby Thaddeus and murders him. Charles “reconstructs” Thaddeus (aka the “infantata”) with the baby’s body parts, animal parts and the heart of one of the aborted fetuses. Nora tells Charles she tried to breastfeed him but it wasn’t milk the baby was craving. We witness bloody claw marks above her breasts. Nora goes on to say:

“We’re damned Charles because of what we did to those girls, those poor innocent girls and their babies.”

So basically Murphy and Falchuk are saying, “Fuck you, reproductive justice!”

By portraying Charles and Nora as greedy, preying on young girls reinforces the notion that all abortion providers are greedy, evil predators. And American Horror Storyisn’t telling us that illegal, back-alley abortions are bad. No, it’s telling us ALL abortions are bad.

The most terrifying aspect of American Horror Story isn’t the shocking gore or gasping plot twists. When our reproductive rights face a daily barrage of attacks, it’s frightening that the series so blatantly perpetuates myths surrounding the fear, stigma and shame of abortion and pregnancy. Reducing women to their reproductive organs, we’re told women’s sexuality and reproduction should scare us and as a result, women’s bodies should be punished and controlled. I’m getting so fucking sick and tired of ignoring sexism, misogyny and anti-choice bullshit just to watch TV.

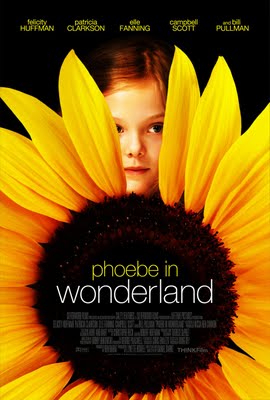

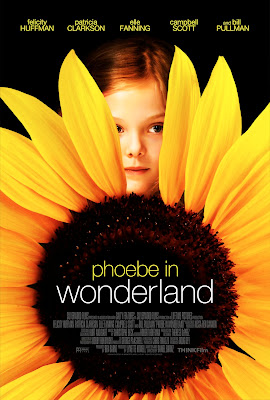

ole falls exclusively to Hillary. She’s a stay-at-home mom trying to write a book while also attempting to care for two young daughters. While her struggle to play The Good Mom definitely lends sympathy to her character—I mean, honestly, what the hell is a good mom?—I couldn’t help but despise her selfishness and blatant disregard for Phoebe’s needs. Even though both parents decide to (finally) get Phoebe into therapy, it’s Hillary who refuses to accept the doctor’s diagnosis, even going so far as to remove Phoebe from therapy, deliberately hiding the diagnosis from her husband.

ole falls exclusively to Hillary. She’s a stay-at-home mom trying to write a book while also attempting to care for two young daughters. While her struggle to play The Good Mom definitely lends sympathy to her character—I mean, honestly, what the hell is a good mom?—I couldn’t help but despise her selfishness and blatant disregard for Phoebe’s needs. Even though both parents decide to (finally) get Phoebe into therapy, it’s Hillary who refuses to accept the doctor’s diagnosis, even going so far as to remove Phoebe from therapy, deliberately hiding the diagnosis from her husband. successfully portrays the societal trend of the working father: he pokes his head in when necessary, checking in on his daughters, and demonstrating just the right balance between quirky annoyance at their neediness and curiosity about their daily lives—he shows up to parent/teacher conferences, he consoles Phoebe when she gets in trouble at school, and he genuinely wants to participate; he’s just not required to maintain the role of The Good Dad—it doesn’t exist.

successfully portrays the societal trend of the working father: he pokes his head in when necessary, checking in on his daughters, and demonstrating just the right balance between quirky annoyance at their neediness and curiosity about their daily lives—he shows up to parent/teacher conferences, he consoles Phoebe when she gets in trouble at school, and he genuinely wants to participate; he’s just not required to maintain the role of The Good Dad—it doesn’t exist.