Written by Rachael Johnson.

“Truth is on the side of the oppressed.” –Malcolm X

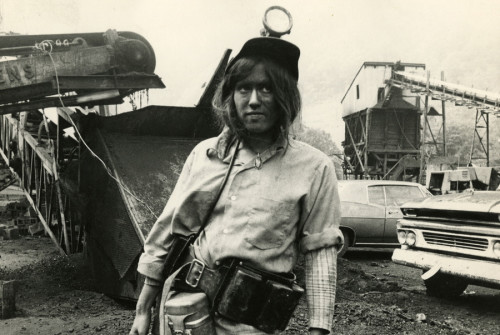

Directed with great spirit and empathy by Barbara Kopple, the documentary, Harlan County, U.S.A. (1976) is the story of an eventful strike in eastern Kentucky. The 13-month-long Brookside Strike (1973-4), as it was called, involved 180 miners from the Duke Power-owned Eastover Mining Company’s Brookside Mine in Harlan County. The film chronicles the miners’ fight to join the United Mine Workers of America, a move prohibited by the mining company when they refuse to sign the contract. Their hard struggle for representation, better wages and working conditions is lived and portrayed as a collective one. The men are joined on the picket lines by their wives who play a central role in the story. Their dramatic journey is understood and depicted as a deeply personal and political one.

In the first few minutes of Harlan County, U.S.A, the viewer is transported into the mines. We watch the men labor, and even have a bite to eat, in the grimy, confined spaces before emerging into the light once more. This is proper political film-making. Kopple takes us into the working men’s world. She sides with the miners and we are encouraged to do so too. She gives us a strong sense of how dangerous the job is. The men’s working conditions are appalling. The miners have had black lung for generations and suffer injuries for which they receive no compensation. The living conditions the workers endure are shameful too. Their houses don’t have indoor plumbing and running water. We see one miner’s wife wash her child in a tin bucket. Kopple’s documentation of these inexcusable living conditions may shock both American and non-American audiences watching today- as they, no doubt, must have done in 1976. U.S. popular culture- particularly Hollywood- does such a good job concealing American poverty that when audiences see it, it always comes as a jolt. This is, perhaps, even the case for people who have few illusions about the American Dream. There are, of course, reminders now and again. The tragedy of Hurricane Katrina, for example, revealed to the world disturbing truths about US economic inequality.

Numbers cited in Harlan County, U.S.A. tell an outrageous tale: coal company profits in 1975 rose 170 percent while workers’ wages rose only 4 percent. As U.M.W. organizer Houston Elmore explains, the miners are victims of a “feudal system.” The story of Harlan County, U.S.A. is one of struggle and resistance to power. The strike rejuvenates and organizes them. It is gruelling, perilous fight too. When they are not being arrested and jailed, they are being intimidated, assaulted and shot at by mining company thugs. Kopple is always with them recording their struggle. At one frightening night-time picket, her camera is attacked. The workers begin to arm themselves too. Tragedy finally strikes when a young miner is murdered. The company soon concedes and the strike ends. While the story of the strike may be a stirring one, and the workers secure their right to unionize, there is neither a neat nor fairytale ending. Some workers are happy with their pay but others express disappointment about their contract. Union compromises like the no-strike clause indicate that the struggle for miners’ rights will continue.

The women of the community play an essential, dynamic role during the strike. As with the men, the struggle strengthens and politicizes them. They join the picket lines too, and block the roads with their bodies to prevent the scabs from getting through to the mines. The women are fully aware of what they are up against. One addresses a judge at court: “You say the laws were made for us. The laws are not made for the working people in this country…The law was made for people like Carl Horn.” Carl Horn was the president of Duke Power at the time. Although the women are not entirely immune from letting personal crap get in the way, they are focused and determined. They are, in fact, incredibly strong. An older lady encourages them to not back down as backing down would mean a return to the dark, hungry days of the 30s. “If I get shot, they can’t shoot the union out of me,” she says. The women are also intimated, assaulted and shot at. The film rightly focuses on the collective but the community does have its characters. The most charismatic woman among them is perhaps organizer Lois Scott. Both an inspiration and a badass, Lois seems frightened of very little in life.

What Norman Yarborough, President of the Eastover Mining Company, says about the miners’ wives at a press conference is extremely revealing. When asked about their role, Yarborough smiles in a patronizing, good-old-boy fashion before conceding that they have played “a big role.” He goes on to say that their activities disturb him: “I would hate to think that my wife had played this kind of role….there’s been some conduct that I don’t think that our American women have to revert to.” Politically active, working-class American women are a clear threat to Yarborough’s natural order and must, therefore, be branded unfeminine and un-American. Women also play a celebrated cultural role in the community. They are a vital part of the musical and political history of the place.

The numerous songs featured in the documentary illustrate the central role music plays in their lives of the mining community. They chronicle the history of Harlan as they rouse and unify its people. The most memorable is “Which Side Are You On?.” Widely recognised as one of the great protest songs of the 20th century, this anthem to worker’s rights was penned by activist, folk song writer, and poet, Florence Reece. A daughter and wife of miners, Reese penned “Which Side Are You On?” during the Harlan strike of 1931. The great woman herself is featured in Harlan County, U.S.A. singing her iconic song at a strike rally.

The documentary focuses on the 1973 strike in Bloody Harlan but it also manifests an understanding of labor history. The miners, like any other exploited group, remember what was done to them decades before. Kopple connects the past to the present through powerful interviews with older residents, film footage and stills. Remembering is essential work, especially in a country where the silencing of historic abuses has always been routine. As writer Milan Kundera once said, “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” Harlan County, U.S.A. is an extremely detailed, multi-layered film. The documentation of other labor-related events and struggles deepen our understanding of the time. Kopple documents leadership challenges and reforms in the union in the early seventies, the extraordinary story of the Mafia-style hit of United Mine Workers President Joseph Yablonski and his wife and daughter by President W.A. Boyle in 1969, as well as the 1968 Farmington, West Virginia mine explosion, a tragedy which killed 78 men.

Kopple gives an in-depth portrait of the men and women of the mining community of Harlan County as well as a gripping account of the strike that transforms them. She never patronizes the people of Harlan and she can never be accused of exploitative class voyeurism. From the very start, she plunges the viewer into the life of the community, and we are with them every step of the way.

Harlan County, U.S.A. is a stirring tribute to working-class kinship and activism. Although it is a story specifically rooted in the history of Harlan, as well as a very American story, the struggle for economic justice it documents is one that transcends regional and national borders. Koppel’s gutsy film-making was rewarded. Harlan County, U.S.A. won Best Documentary Feature at the Academy Awards that year. It is, without a doubt, one of the greatest documentaries ever made, and it should be shown in every school in the United States.