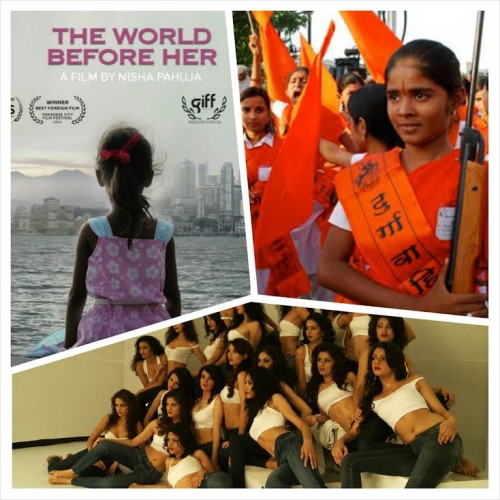

This guest post by AP appears as part of our theme week on Asian Womanhood in Pop Culture.

“All Hindi films come from Mother India” – Javed Akhtar (lyricist, poet and scriptwriter)

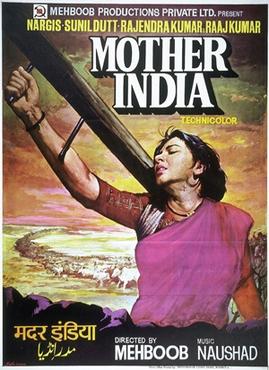

Many people consider Mother India (1957) the definitive Hindi film. This legendary film won countless accolades, earned higher revenues than any film before it, and ran for more than three decades. Wondering what all the fuss what about, I watched it recently for the first time. It’s highly entertaining and moving, with a great plot, dialogues and music. It’s three hours long, so I spread my viewing over a couple of days. Despite its length, it drags very little.

The film tells the story of Radha (Nargis), a farmer, from her days as a young bride to her old age. When Radha gets married and moves to her husband’s house, she lives a happy life until she learns that her mother-in-law has taken a loan from the usurious village moneylender to pay for the wedding. Unable to repay the loan, and beset by tragic accidents and a disastrous flood, the family eventually becomes impoverished. Radha loses her husband and mother-in-law, and raises her children on her own. She suffers great hardship but raises them to adulthood, and even faces down the crude advances of the moneylender.

Years pass; the family survives, but continues to be exploited by the moneylender. One of Radha’s sons, Birju, grows to hate the moneylender, and finally snaps. Circumstances lead him to become a bandit. He kills the moneylender, and for further revenge, abducts his daughter.

Radha is distraught: she cannot stand to see a girl’s honour violated. She threatens to kill Birju, telling him that dishonouring any girl of the village, is tantamount to dishonouring the entire village, which includes his own mother. When Birju tries to ride away with the kidnapped girl, Radha shoots him dead.

“I am a woman. I can give up a son, but I can’t give up honour.”

Several years pass; Radha is an aged woman. There is a hopeful note in the air: modern technologies are being introduced by the government to increase agricultural productivity and lessen the peasant’s burden. The villagers revere Radha for all she’s done, and invite her to inaugurate the new irrigation canal. Water the colour of blood flows through the canal, a reminder of Radha’s sacrifices.

After watching the film, I understand why it was such a big deal. It’s because it captured the mood of the nation, its values, hopes and aspirations. At the time, about 80 percent of Indians were engaged in agriculture. The colonial yoke had been thrown off. The film reflects the period’s broad consensus that for the nation to progress, two things were required: food security through advancement in agriculture, and rapid industrialization through investment in heavy machinery. The film is a celebration of farming, and shows reverence of the land that nurtures us.

The movie also celebrates the idea of woman as the nation’s pillar of strength. I’ll focus on this theme, and on the character of Radha.

The Bad

In some ways, Mother India is quite conventional. Its intended messages about women are regressive from a feminist point of view. The movie conveys that the ideal woman is nurturing, self-sacrificing and hardworking. It ignores the reality that women did all of this for very little reward. For all their sacrifices, did woman have a say even in basic decisions like how many children to have? Not much. In the 1950s, when the movie was released, women’s legal rights were severely restricted; for example, the progressive legislations introduced by stalwarts like B. R. Ambedkar and Jawaharlal Nehru, for Hindu women’s inheritance and marriage rights, had been stonewalled and diluted in Parliament.

Mother India highlights the plight of the farmer, but glosses over or erases the specific difficulties faced by women farmers specifically: lack of access to resources, invisibilization of their labour, and their self-deprivation in times of scarcity. In times of food insecurity, adult women often deprive themselves and girl children of adequate food. It is not necessarily forced upon them; more often it’s a choice (made in the context of patriarchal society).

Mother India treats Radha’s abnegating nature as a positive. Look how nobly she suffers for her husband and sons, the movie seems to say. In real life, such glorification of women’s suffering enables an exploitative system of economic growth on the backs of underpaid, overworked women. They get nothing except lip service, sometimes not even that.

Lastly, a central theme of the movie is honour/modesty. Radha values honour – her own and other women’s – over and above everything else. Maintaining honour is the prime duty of a woman. Her honour is not just her own, but the family’s, the village’s, and by extension the nation’s. But the problem with honour is that to maintain it, women’s mobility, freedom and sexuality must be tightly controlled.

The Good

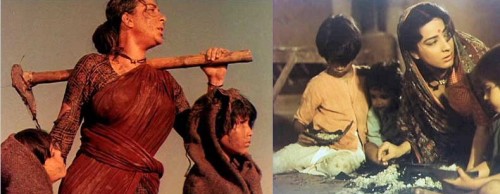

Having said all that, there are some ways in which the character of Radha is a triumph for women’s representation in Indian cinema. She is a formidable, determined woman. She is uneducated (she can’t read the moneylender’s accounts), but she is tough and practical. She has the skills, knowledge, and the will to protect and raise her children. She never dithers or acts silly. She commands respect from her sons, from the villagers, and from the audience. She has to make tough choices in bleak circumstances. She breaks two negative stereotypes: that women are not intelligent, capable decision-makers, and that women don’t do arduous labour. In Mother India, it is the woman who builds the nation with her sweat and toil.

Through images, music, and lyrics, the movie establishes Radha’s sheer physical strength. The foregrounding of physical power is rare in today’s female characters, but appropriate for a portrayal of a rural woman.

On one hand, the audience is inspired (maybe even awestruck), by Radha’s resilience, and by her steadfast adherence to her moral code. But at the same time her humanity takes centre stage, and she is allowed to express a range of emotions. She suffers devastating losses, is disrespected, and is sometimes terrified for herself and her family. She also enjoys periods of relative prosperity, good harvests, the joys and frustrations of family life.

In the climactic scene, Radha shoots dead her son Birju. Framed starkly against the sky, Radha is an awe-inspiring figure, a wrathful goddess. She is rendered human the next minute, when she runs to her dying son and holds him, weeping.

The last point about Radha is her love for the land. She does backbreaking work with dignity and forbearance, not just because she has to feed her children, but because she considers the land her mother.

On one hand, Mother India suffers from fatal flaws – the glorification of traditional gender roles and modesty/honour. On the other hand, the film’s recognition of women’s contribution to building then nation, its characterization of Radha, and its reverence for farmers, are its triumphs. Paradoxically, the character of Radha is mired in stereotypes, but also represents women’s labour, and can serve as a source of strength and inspiration for Indian women.

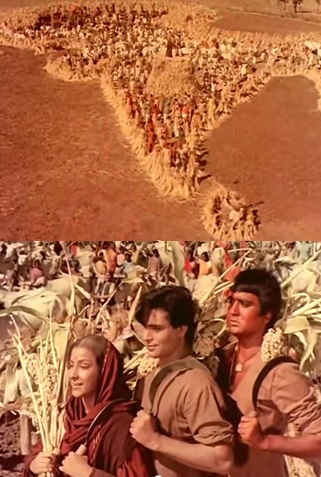

The agricultural focus is also key. I’ll end with this evocative scene: the villagers have weathered calamities, and there is a song celebrating a good harvest. With the last line of the song, there is an image of haystacks shaped like the map of India, inside which farmers are singing and dancing. Today, with agriculture in dire straits in India and several other parts of the world, Mother India’s image of agricultural prosperity becomes even more important to work toward.

AP is a student. She likes traveling, good food, and movies.