This is a guest post by Nandini Rathi.

Chinmayee, a young girl at the Durga Vahini camp in Aurangabad, takes pride in the fact that unlike before, she has no Muslim friends anymore since her thoughts have matured in Hindutva at Durga Vahini. She takes exclusive pride in Hindu culture and looks forward to strengthen her thoughts about it in the future camps.

In another part of the country, Ruhi Singh, a 19-year-old Femina Miss India 2011 aspirant laments that her hometown, Jaipur, is not supportive of her ambitions as many people fear that allowing girls to get educated and choose their own careers will be tantamount to a loss of culture. “As much as I love my country and my culture,” she says, “I consider myself to be a very modern, young girl. And I want my freedom.”

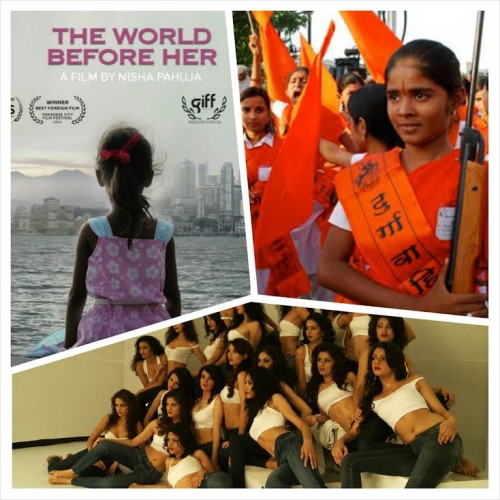

This freedom, which is echoed by other characters in the The World Before Her (Pahuja, 2012), is of being who they want to be and living as they choose to live, without constantly having to worry about safety. Even though many institutions nurture the dream and promise to fulfill it, they come with strings attached. Indo-Canadian director Nisha Pahuja works hard in this phenomenal documentary to reveal some tensions within a rapidly modernizing India, through the microcosm of the Miss India beauty pageant and the Hindu nationalism of Durga Vahini. Apart from raising questions about objectification of women in the glamour industry, the movie also touches upon the state of communalism and religio-nationalism in India.

After stumbling upon its fascinating Kickstarter pitch video almost two years ago, I finally watched The World Before Her on Netflix. It was thoroughly engaging and every bit worth the time as Pahuja juxtaposes two diametrically opposite, extreme worlds of modern Indian women — behind the walls of the Miss India pageant boot camp in Mumbai and the Durga Vahini physical training camp in Aurangabad. Durga Vahini is the women’s wing of Bajrang Dal, a subsidiary of the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP), a Hindu right-wing organization in India.

Beauty pageants deem all their critics to be a singular species from the “Old World.” Right-wing Hindu organizations see beauty pageants as a sign of Western attack on their frozen-in-time, monolithic conception of “Indian culture.” Archival footage informs the audience of the Hindu right wing’s various physical attacks on girls in pubs, in the name of desecration of this “Indian/Hindu culture.” In making The World Before Her, Pahuja chooses to walk the neutral line by avoiding a personal stand and trying to hold up a mirror instead. In an interview with First Post, she says that she made this documentary in an attempt to create a dialogue. Her humanizing, vérité cinema approach works to that effect.

The narrative of The World Before Her cuts back and forth between a Miss India crown aspirant, the sweet 19-year-old Ruhi Singh and a Durga Vahini camp youth leader and staunch VHP supporter, the 24-year-old Prachi Trivedi. It is full of ironies along the way, as the two radically opposite worlds come out to be more similar than what we initially imagined.

The doors of opportunity and exposure open far and wide for the Miss India crown-bearers. Pahuja claims early on that the beauty and glamour industry is one of the few avenues in India where women stand at par with men. Ruhi has the drive to win and the full moral support of her family. However, for many girls, to make it as far as the Miss India pageant is a difficult task of overcoming family reluctance as well as personal resistances. These girls understand that culture is, and was, never a fixed entity — but one that constantly evolves with time and contact with other cultures. Contestant Shweta says that that they are often accused of becoming “American,” to which she smartly argues that she isn’t becoming American for wearing jeans or eating a burger, anymore than Americans are becoming Indians for taking up Yoga.

42 Durga Vahini camps veteran and leader Prachi Trivedi is easily the most fascinating character, who likes to command others and talks to Pahuja with breathtaking candor. Prachi strongly believes in her Hindu nationalism which is based on the idea that the golden age of Hindu India was marred by outsiders who are still the enemy within. She has no qualms about killing any moment for her religion. Her father is cheerfully antagonistic to what she wants to do with her life. He fulfills his duty towards Hindutva by teaching the young girls in the camp — who the “bad guys” are, aka Muslims and Christians. Unlike Ruhi’s parents, Prachi’s father believes that she doesn’t have any rights besides what he gives her. One gets goosebumps when Prachi says that she forgives him for all the bullying, because it’s enough for her that he let her live — and didn’t kill her at birth for being a girl child, like many others do.

Prachi does not think her life is intended for marriage and family. She wants to dedicate her whole life to the Parishad (Vishva Hindu Parishad). But she is not sure if, being a girl, she has the freedom to make such a choice. The choice of a woman to stay single and not produce children is completely outrageous to the Parishad as well as her father. Her candid self-awareness reveals her vulnerable side in that poignant moment; it is so easy to forget then, that her ambition is to become the next Sadhvi Pragya Singh Thakur of the Malegaon bomb blast notoriety.

There is a palpable tension in the values inculcated at the Durga Vahini camp. “Sher banne ki prakriya yahan se shuru hoti hai (the process of becoming a lion begins here)”, says one of the camp instructors to the girls. On one hand, they want to increase young women’s confidence so they can be independent enough to rise to the call of action for the religio-nation. On the other hand, they are taught the dharma (duties) of a Hindu woman — in which chasing careers is a futile, corrupting, Western pursuit and only a “high moral character” matters, especially in the role of a wife and mother. Women’s action and power matters and is extremely important, but only while it actively and appropriately services the religious nationalism. They are nowhere expected to take liberties or choose their own paths. A conflict from this is likely underway in the future, as it is for Prachi.

On the occasion of Nina Davuluri’s crowing as Miss America, Rediff columnist, Amberish K. Diwanji noted that India’s beauty pageants do not reflect its diversity. Although the issue of inclusion of an Indian dalit or tribal woman in a beauty pageant is much more complicated (keeping in mind, the economic disparities, rural/urban divides and cultural clashes), simply speaking, the definition of beauty in pageants (and the glamour industry) is disturbingly narrow. I was shocked by Cosmetic Physician Dr. Jamuna Pai’s ease in administering Botox injections to achieve some ‘golden rule’ in the facial proportions of the contestants. Add to it, the application of face-whitening chemicals to burn through their tans. Miss India trainer, Sabira Merchant, describes the Miss India pageant boot camp as a factory, a manufacturing unit where beauty is controlled and prepared to meet the demands of the national and international fashion industry. The rough edges have to be straightened out and polished. The routine of the camp makes sure that any personal inhibitions on the woman’s part have been overridden. “The modern Indian woman” is produced for the world to look at.

“… I always had this vision of putting cloaks on women so we can’t see their faces, only their legs — and then decide who has THE best pair of legs. Sometimes you may get thrown — beautiful girl, lovely hair, she walks so good, she has a great body — we don’t want to see all that! I just want to see beautiful, hot legs!” –Marc Robinson, former model and Pageant director

Out of context, this would read as a perverted person’s fetish fantasy. I am trying to remind myself that Robinson speaks for the beauty industry– and so I shouldn’t think of only him as a creep. The parading Ku Klux Klan-esque figures are the contestant ladies, who ought to feel hot when they catwalk up to him like that.

What about self-respect and dignity, one is forced to wonder. Contestant Ankita Shorey, who felt claustrophobic during the cloak session, reflects on her feelings about bending over backwards for the sake of success.

“Aurat ko maas ke tukde ki tarah plate par rakhkar serve kiya jaaye, aur taango, breast aur hips ke aadhaar par taya kiya jaaye – ye toh poori duniya ki aurat zaat ke liye be-izatti ki baat hai, khaali Hindustaan ke liye nahin.” — an Activist in the 1996 archival footage of demonstrations against hosting Miss World in India

(To serve a woman like a piece of flesh on the plate, and to judge her on the basis of the size of her legs, hips and breasts – it is disrespectful to the womankind all over the world – not just to women of India)

My roommate’s and my reaction was — that’s true, she’s right. She expressed a genuine concern that would resonate with anyone who is even mildly concerned about the male gaze and the objectification of women’s bodies in media/glamour/film industry. Her saffron clothes suggest that she could be from a Hindutva-espousing party that sees pageants as a plain attack on “Indian culture”. It’s that awkward moment when feminists and right wingers find themselves to be bed fellows on this cause.

The formidable Ms. Merchant says in the second half: “There is a dichotomy and the girls seem like very with it, but they have traditional values. Should we go with the Old World or should we go with the New World? When they ask me that question, I always tell them to go with the New World, because the only thing constant in life is what? Change.” Just as Hindutva-espousing groups like VHP have no reason to not promote a blind hatred of Muslims and Christians, the beauty industry has no need or desire to parse out what the “New World” values really are.

P.S. While there is definitely a dichotomy between the old ideas and the new ones, Pahuja has chosen extreme, contrasting examples for the most narrative oomph. It creates a better story, which I am all for. The documentary is also timely as it is being viewed at a time when the Hindu right in India is gaining power and popularity (since Narendra Modi’s victory at the center). That said, it is crucial to remember that girls who participate in beauty pageants and those who participate in the likes of Durga Vahini camps are extreme minorities. They do not represent the majority.

Nandini Rathi is a recent graduate from Whitman College in Film & Media Studies and Politics. She loves traveling, pop culture, editing, documentaries, and adventures. Now living in New York city, she wants to be immersed in filmmaking, journalism, writing and nonprofit work to ultimately be able to contribute her bit toward making the world a better place. She blogs at brightchicdreams.wordpress.