Written by Brigit McCone as part of our theme week on Asian Womanhood in Pop Culture.

In our conversation about the sexism of “friendzoning,” it’s easy to forget it is a traditionally female institution. It is women who are expected to be passive in romance, and to express sexual desire indirectly through friendship. When the word “friendzone” was coined in a 1994 episode of Friends, it was the comically feminized Ross who was dubbed “Mayor of the Friendzone.” The rage of many friendzoned men expresses their resentment of romantic rejection, but also their frustration at feeling feminized by their failure to conquer; conquering neither the girl nor their emotions, they remain stranded in a typically feminine limbo. It is women who are supposed to naturally play “beta chumps.”

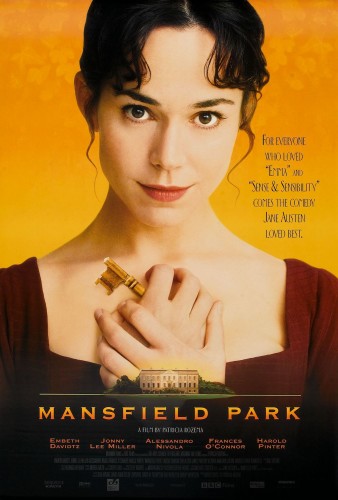

Traditionally, female portraits of friendzoning were fantasies of eventual victory through silent emotional martyrdom. Fanny Price, of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, encourages both her love Edmund and his love Mary to confide in her, while stewing inwardly about how “deceived” Edmund is in Mary, before using Mary’s trust to passive-aggressively poison Edmund against her. At no point does Fanny consider taking an active role by expressing her feelings. When Edmund’s brotherly love turns to romance, Austen makes clear he is on the rebound or “exactly in that favorable state which a recent disappointment gives.” Critic and Booker Prizewinner Kingsley Amis has branded Fanny “a monster of complacency and pride” who dominates “under a cloak of cringing self-abasement,” which is just about the perfect summary of the friendzone-moaning “Nice Guy.”

The friendzoning of “quiet worth,” in favor of spirited charm, also crops up in Anne Brontë’s Agnes Grey, whose heroine is obviously based on Anne herself, but named after her beloved Weightman’s real-life love, Agnes Walton. The fictional Agnes, too, spends time stewing and resenting her rival, in one of literature’s most wincingly honest portraits of unrequited love, before Weston (the fictional alias of Weightman) improbably reveals that he loves “Agnes” after all. In Some Kind Of Wonderful, Mary Stuart Masterson plays a girl friendzoned because of her tomboy qualities, like Doris Day in Calamity Jane, rather than the classic “quiet worth,” but Masterson is classically self-sacrificing and passive as she waits for the hero to “come to his senses.” Later friendzoned women, from Kristen Scott Thomas in Four Weddings And A Funeral to Julia Roberts in My Best Friend’s Wedding (side note: was I the only one on Bitch Flicks who loved that deliciously acid satire?), have been forced to admit romantic defeat as punishment for such passivity, rather than passively rewarded for emotional martyrdom. But India, a country popularly viewed as more traditional in its gender roles, offers a classic, female friendzone fantasy of tomboy rejection in Bollywood’s own answer to Some Kind of Wonderful, 1998 smash hit Kuch Kuch Hota Hai.

The film divides neatly into two halves. In the first half, tomboy Anjali (Kajol) is romantically dismissed by her buddy, Rahul (Shahrukh Khan), in favor of a more conventionally feminine and sexually confident rival, Tina (Rani Mukherji). Poor Anjali is a short-haired frump, you see, in the She’s All That tradition of luminously gorgeous women with faintly unflattering and (*gasp*) masculine fashion sense. In the second half, Rahul and Anjali meet again after Tina’s death, when Anjali has transformed into a saree-wearing, long-haired and conventionally feminine beauty, and they fall in love.

In the first half, Anjali constantly beats Rahul at basketball. In the second half, her feminine saree and hair get in her way, she is distracted by her sexual attraction to Rahul, and she loses, to chants of “girls cannot play basketball.” Indeed, the film tells us, girls cannot play basketball, but only because they want boys to like them. In the first half, Anjali is assertive and outspoken, only failing to tell Rahul of her feelings because he is in love with Tina by the time she realizes them. In the second half, Anjali is shy and passive, allowing her final fate to be decided by her fiancé, Salman Khan, playing a slimier spin on the thankless “Bill Pullman in Sleepless in Seattle” role. The plot gratifies female viewers, reassuring them that they are perfectly capable of beating men, but are forced to play the passive role by unjust, anti-tomboy romantic discrimination. It equally gratifies male viewers, reassuring them that they have the romantic power to discipline women into unthreatening beauties. By supplying excuses all around, Kuch Kuch Hota Hai upholds the status quo while venting its resulting frustrations; the performances lovingly celebrate female feistiness, while the plot constantly punishes and suppresses it in favor of traditional ideals of self-sacrifice and emotional martyrdom. Cue predictable feminist outrage. You already know everything I would write. So instead, I’d like to focus on another aspect of the film: its utter contempt for male agency. Yes, male.

Rahul does not become reunited with Anjali by chance. As tomboy Anjali takes a train out of Rahul’s life, to avoid interfering in his relationship with Tina, her eyes tearfully meet Tina’s on the platform. She passes her scarf to Tina, as though to leave a piece of herself with Rahul, recalling Anne Brontë’s fusion of friendzoned and beloved in her fictional “Agnes.” In that moment, Tina narrates, “Anjali’s silence told me everything.” Tina realizes that Anjali is entitled to Rahul, not because of Rahul’s feelings for Anjali, but because of Anjali’s feelings for Rahul. After consciously choosing to bear Rahul a child, knowing that she will die in childbirth and withholding this knowledge from him, Tina commands Rahul to name their daughter “Anjali” and leaves that daughter a series of letters to open every birthday. The final letter, on her eighth birthday, is the one that narrates the story of Tina, Rahul, and the original Anjali, instructing child-Anjali to reunite Rahul with her namesake. This “letters from beyond the grave” trope echoes P.S. I Love You, in which Gerard Butler’s husband writes a series of letters for his wife to open after his death, guiding her through her grieving process before giving his blessing to her finding new love. I was no fan of that film’s leprecorniness, but can we take a moment to admit how boundless our feminist outrage would be, if P.S. I Love You featured Butler writing to the couple’s 8-year-old son and instructing him to “fulfil his father’s dream” by manipulating his mother into a relationship with a lover of Butler’s choosing? Not to mention that, since Tina died shortly after giving birth, she had absolutely no knowledge of her daughter’s character, emotional maturity or tactical skill.

Kuch Kuch Hota Hai even underlines the cruelty of this maneuver: the camera pulls in on Rahul’s moist eyes as he admits that child-Anjali has “got something which even I don’t have. Her mother’s letters.” The film glorifies Tina’s noble self-sacrifice, paralleling her martyrdom with the goddess Durga‘s feminine ideal, but is this truly admirable? Tina deprived Rahul of any say over risking her life; she wrote detailed instructions for Rahul’s romantic future to an eight-year-old, but didn’t prepare a single letter for her supposedly beloved husband. Each of Tina’s unselfish actions serve to hurt and exclude Rahul, stripping him of his agency and undermining the dignity of his love, though it was deep enough to resolve him on never remarrying after losing Tina. Luckily, though, Rahul does turn out to have subconscious romantic feelings for Anjali, despite all behavior to the contrary. Phew. It would otherwise be distinctly awkward to raise a daughter whose very name is a constant reminder that your true love really wanted you to hook up with your college friend, even before that daughter is brainwashed that it is her sacred duty to “get Anjali back into [her] father’s life.”

Writer-director Karan Johar admits, in the DVD’s special features, “I always know a woman better, actually, I’m more comfortable with a woman’s character than a man’s.” Kuch Kuch Hota Hai succeeds in spite of this bias towards female entitlement, due to infectious music and romantic chemistry between its actors. Kajol and Shahrukh Khan recapture their spark from smash hit Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge. Kajol brings extraordinary emotional transparency and rawness to her role, utterly fearless of looking foolish. We cringe for her, but it is this whole-heartedness that makes her sympathetic. Tomboy Anjali deserves Rahul; she is the only character who respects his will. When she discovers his love for Tina, the soundtrack sings, “You did not remember me, there’s nothing more left to say,” signaling her tearful resignation. Advocating abandoning your college education, because of romantic disappointment, is hardly a good model for girls, but this decision dramatizes Anjali’s willingness to respect Rahul’s relationship with Tina. She is also the only character who honors his vow never to remarry.

When Anjali and Rahul are finally reunited, at his daughter’s summer camp, there is a particularly lovely scene on a bench at night, perfectly capturing the awkwardness of re-establishing intimacy after long estrangement. Yet the scene ends with child-Anjali popping up and shaking her head, her assumed entitlement to monitor and manipulate her father’s romance going utterly unchallenged. The genuine chemistry between Kajol and Shahrukh, as well as their characters’ shared innocence of the matchmaking conspiracy, make it easy to overlook the narrative’s justification of romantic interference.

The concept of indirect female power is nothing new, nor is it particular to India. Ever since Salomé danced for the head of John the Baptist, femme fatales have achieved their goals indirectly by influencing men. Lady Macbeth becomes an “unsexed” monster out of ambition for her husband alone; her soliloquies never mention any personal desire to be queen. Tendencies in Indian culture to justify matriarchal manipulation have been satirized by director Gurinder Chadha, particularly in her black comedy It’s A Wonderful Afterlife. What makes Kuch Kuch Hota Hai interesting is how clearly it shows the link between suppressing direct power and promoting indirect power. The film’s first half punishes the heroine’s direct assertiveness; its second half relieves female frustration by glorifying passive womanhood’s power over men. It is Rahul’s mother, a pious and traditional Indian matriarch, who leads the conspiracy. She declares, “the way we think and the things we say have a deep impact on our children” to set up a joke about her granddaughter learning the word “sexy” from Rahul, yet unquestioningly endorses that granddaughter’s matchmaking interference, whether child-Anjali is praying to delay weddings or emotionally blackmailing Rahul with calculated crying. This grandmother teaches that “men are very weak,” pressuring Rahul into remarrying because his child “needs a mother.” The way we think and the things we say have a deep impact on our children. Alongside its touching romance, Kuch Kuch Hota Hai portrays the indoctrination of a very young girl into a culture that normalizes the manipulation of men, as compensation for its suppression of women.

I highly recommend Kuch Kuch Hota Hai as an introduction for the Bollywood beginner, boasting excellent performances, acutely human moments in the midst of its melodrama and slapstick, and catchy tunes. You’ll laugh, you’ll cry, you’ll forget that the film’s underlying assumptions about gender roles are fundamentally counterproductive for both sexes. But whether it is her fiancé’s final control over the heroine’s decision or the female conspiracy to determine the hero’s choice, there is only one word for Karan Johar undermining his characters’ autonomy this way: deewana (bonkers).

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0QoZ8QcveC8″]

Brigit McCone did not allow her slight crush on Shahrukh Khan to bias this review. She writes and directs short films and radio dramas. Her hobbies include doodling and terrible dancing in the privacy of her own home.