| Brad Pitt stars in Best Picture nominee Moneyball |

| Casey, played by Kerris Dorsey |

| Antiquated gender dynamics mar Moneyball |

The radical notion that women like good movies

| Brad Pitt stars in Best Picture nominee Moneyball |

| Casey, played by Kerris Dorsey |

| Antiquated gender dynamics mar Moneyball |

|

| Michelle Williams as Marilyn Monroe |

|

| Marilyn Monroe |

———-

Danielle Winston is a Manhattan based screenwriter and playwright. Her articles are regularly published in regional and National Magazines. She’s also a yoga teacher and creator of Writer’s Flow Yoga.

|

| Meryl Streep and Margaret Thatcher |

|

| Michelle Williams as Marilyn Monroe |

|

| Marilyn Monroe |

Let me say up front that I’m aware that I’m supposed to feel sorry for Sandra Bullock this week. She’s purported to be “America’s sweetheart” and all, she has always seemed like a fairly decent person (for an actor), and I think her husband deserves to get his wang run over by one of his customized asshole conveyance vehicles, but I’m finding it difficult to feel too bad. I mean, who marries a guy who named himself after a figure from the Old West, has more tattoos than IQ points, and is known for his penchant for rockabilly strippers? Normally I’d absolve Bullock of all responsibility for what has occurred and spend nine paragraphs illustrating the many reasons Jesse James doesn’t deserve to live, but I’ve just received proof in the form of a movie called The Blind Side that Sandra Bullock is in cahoots with Satan, Ronald Reagan’s cryogenically preserved head, the country music industry, and E! in their plot to take over the world by turning us all into (or helping some of us to remain) smug, racist imbeciles.

The movie chronicles the major events in the life of a black NFL player named Michael Oher from the time he meets the rich white family who adopts him to the time that white family sees him drafted into the NFL, a series of events that apparently proves that racism is either over or OK (I’m not sure which), with a ton of southern football bullshit along the way. Bullock plays Leigh Anne Tuohy, the wife of a dude named Sean Tuohy, played by — no shit — Tim McGraw, who is a fairly minor character in the movie despite the fact that he is said to own, like, 90 Taco Bell franchises. The story is that Oher, played by Quinton Aaron, is admitted into a fancy-pants private Christian school despite his lack of legitimate academic records due to the insistence of the school’s football coach and the altruism of the school’s teachers (as if, dude), where he comes into contact with the Tuohy family, who begin to notice that he is sleeping in the school gym and subsisting on popcorn. Ms. Tuohy then invites him to live in the zillion-dollar Memphis Tuophy family compound, encourages him to become the best defensive linebacker he can be by means of cornball familial love metaphors, and teaches him about the nuclear family and the SEC before beaming proudly as he’s drafted by the Baltimore Ravens.

I’m sure that the Tuohy family are lovely people and that they deserve some kind of medal for their good deeds, but if I were a judge, I wouldn’t toss them out of my courtroom should they arrive there bringing a libel suit against whoever wrote, produced, and directed The Blind Side, because it’s handily the dumbest, most racist, most intellectually and politically insulting movie I’ve ever seen, and it makes the Tuohy family — especially their young son S.J. — look like unfathomable assholes. Well, really, it makes all of the white people in the South look like unfathomable assholes. Like these people need any more bad publicity.

Quentin Aaron puts in a pretty awesome performance, if what the director asked him to do was look as pitiful as possible at every moment in order not to scare anyone by being black. Whether that was the goal or not, he certainly did elicit pity from me when Sandra Bullock showed him his new bed and he knitted his brows and, looking at the bed in awe, said, “I’ve never had one of these before.” I mean, the poor bastard had been duped into participating in the creation of a movie that attempts to make bigoted southerners feel good about themselves by telling them that they needn’t worry about poverty or racism because any black person who deserves help will be adopted by a rich family that will provide them with the means to a lucrative NFL contract. Every interaction Aaron and Bullock (or Aaron and anyone else, for that matter) have in the movie is characterized by Aaron’s wretched obsequiousness and the feeling that you’re being bludgeoned over the head with the message that you needn’t fear this black guy. It’s the least dignified role for a black actor since Cuba Gooding, Jr.’s portrayal of James Robert Kennedy in Radio (a movie Davetavius claims ought to have the subtitle “It’s OK to be black in the South as long as you’re retarded.”). The producers, writers, and director of this movie have managed to tell a story about class, race, and the failures of capitalism and “democratic” politics to ameliorate the conditions poor people of color have to deal with by any means other than sports while scrupulously avoiding analyzing any of those issues and while making it possible for the audience to walk out of the theater with their selfish, privileged, entitled worldviews intact, unscathed, and soundly reconfirmed.

Then there’s all of the southern bullshit, foremost of which is the football element. The producers of the movie purposely made time for cameos by about fifteen SEC football coaches in order to ensure that everyone south of the Mason-Dixon line would drop their $9 in the pot, and the positive representation of football culture in the film is second in phoniness only to the TV version of Friday Night Lights. Actually, fuck that. It’s worse. Let’s be serious. If this kid had showed no aptitude for football, is there any way in hell he’d have been admitted to a private school without the preparation he’d need to succeed there or any money? In the film, the teachers at the school generously give of their private time to tutor Oher and help prepare him to attend classes with the other students. I’ll bet you $12 that shit did not occur in real life. In fact, I know it didn’t. The Tuohy family may or may not have cared whether the kid could play football, but the school certainly did. It is, after all, a southern school, and high school football is a bigger deal in the South than weed is at Bonnaroo.

But what would have happened to Oher outside of school had he sucked at football and hence been useless to white southerners? What’s the remedy for poverty if you’re a black woman? A dude with no pigskin skills? Where are the nacho magnates to adopt those black people? I mean, that’s the solution for everything, right? For all black people to be adopted by rich, paternalistic white people? I know this may come as a shock to some white people out there, but the NFL cannot accommodate every black dude in America, and hence is an imperfect solution to social inequality. I know we have the NBA too, but I still see a problem. But the Blind Side fan already has an answer for me. You see, there is a scene in the movie which illustrates that only some black people deserve to be adopted by wealthy white women. Bullock, when out looking for Oher, finds herself confronted with a black guy who not only isn’t very good at appearing pitiful in order to make her comfortable, but who has an attitude and threatens to shoot Oher if he sees him. What ensues is quite possibly the most loathsome scene in movie history in which Sandra Bullock gets in the guy’s face, rattles off the specs of the gun she carries in her purse, and announces that she’s a member of the NRA and will shoot his ass if he comes anywhere near her family, “bitch.” Best Actress Oscar.

Well, there it is. Now you see why this movie made 19 kajillion dollars and won an Oscar: it tells a heartwarming tale of white benevolence, assures the red state dweller that his theory that “there’s black people, and then there’s niggers” is right on, and affords him the chance to vicariously remind a black guy who’s boss thr0ugh the person of America’s sweetheart. Just fucking revolting.

There are several other cringe-inducing elements in the film. The precocious, cutesy antics of the family’s little son, S.J., for example. He’s constantly making dumb-ass smart-ass comments, cloyingly hip-hopping out with Oher to the tune of Young M.C.’s “Bust a Move” (a song that has been overplayed and passe for ten years but has now joined “Ice Ice Baby” at the top of the list of songs from junior high that I never want to hear again), and generally trying to be a much more asshole-ish version of Macaulay Culkin in Home Alone. At what point will screenwriters realize that everyone wants to punch pint-sized snarky movie characters in the throat? And when will I feel safe watching a movie in the knowledge that I won’t have to endure a scene in which a white dork or cartoon character “raises the roof” and affects a buffalo stance while mouthing a sanitized rap song that even John Ashcroft knows the words to?

And then there’s the scene in which Tim McGraw, upon meeting his adopted son’s tutor (played by Kathy Bates) and finding out she’s a Democrat, says, “Who would’ve thought I’d have a black son before I met a Democrat?” Who would have thought I’d ever hear a “joke” that was less funny and more retch-inducing than Bill Engvall’s material?

What was the intended message of this film? It won an Oscar, so I know it had to have a message, but what could it have been? I’ve got it (a suggestion from Davetavius)! The message is this: don’t buy more than one Taco Bell franchise or you’ll have to adopt a black guy. I’ll accept that that’s the intended message of the film, because if the actual message that came across in the movie was intentional, I may have to hide in the house for the rest of my life.

I just don’t even know what to say about this movie. Watching it may well have been one of the most demoralizing, discouraging experiences of my life, and it removed at least 35% of the hope I’d previously had that this country had any hope of ever being anything but a cultural and social embarrassment. Do yourself a favor. Skip it and watch Welcome to the Dollhouse again.

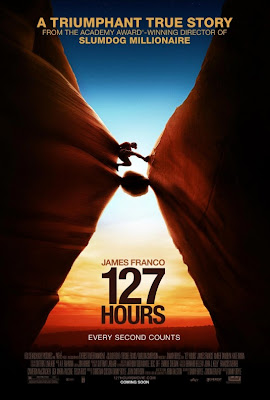

The rest of the movie takes place in the canyon–a claustrophobic nightmare that only works because Franco is apparently an amazing actor–and inside Franco’s mind, through flashbacks of his super hot (gasp) blond ex-girlfriend and the phone calls from his mom and sister that he clearly stupidly ignored prior to his departure. He also hallucinates some crazy shit, like a giant Scooby-Doo blowup doll that’s soundtracked to that ghoulish laughter reminiscent of the last few seconds of Thriller. Yeah! And though it sounds absolutely insane, it’s why the film works. Boyle takes a narrative about a guy struggling to get out of a hole and turns it into an action film, a radio show, a documentary, a commercial, a disaster movie, a cartoon, and a comedy. About a guy struggling to get out of a hole.

Not that there aren’t a few impossible-to-deal-with moments. The final scene, which is poignant enough on its own, insists on beating the audience over the head with its call to EXPERIENCE EMOTION, courtesy of this ridiculous Dido & A.R. Rahman song. And I still can’t quite figure out how the closeup shots of ice-encased Gatorade and Mountain Dew add anything more than advertising revenue, as much as I’d like to argue that, “If I were trapped in a cave, about to die, drinking my own urine, toying with the idea of amputating a limb, I’d totally hallucinate all these brand-name beverages from Pepsico.”

And yes, god, seriously, The Women. I know this is a movie about Ralston’s journey. I respect that and enjoyed watching the innovative ways Boyle used split screens, reverse zooms, fantastical elements, warped focus, and speed variations to tell Ralston’s story in a way I can’t imagine another director successfully telling it. That doesn’t mean I could ignore my own cringing every time a woman entered the frame. The ex-girlfriend clearly serves as a vehicle to show Ralston’s loner-ness; see, he pushed her away all cliche-like. We know this because she says Very Important Things to him. “You’re going to be so lonely,” she yells, after he silently (but with his eyes!) asks her to leave a sporting event they’re attending. (I want to say hockey?)

His hallucinations suck, too. His sister shows up in a wedding dress. His sister showing up in a wedding dress clearly serves as a vehicle to make us feel bad that he’ll be missing Very Important Life Events if he dies, like his sister’s wedding. More pointlessly, the hallucinated sister, who might have one speaking line if I’m being generous, is played by Lizzy Caplan, an actress who’s had large roles in True Blood, Party Down, Hot Tub Time Machine, Cloverfield, and Mean Girls. Instead of engaging with the film, I found myself taken completely out of it, as I wondered why they would cast an actress who’s clearly got more skills than standing in a wedding dress, looking sullen and disappointed, to stand in a wedding dress looking sullen and disappointed.

So, the first two women (the lost ones) show Ralston’s carefree coolness. The ex-girlfriend illustrates Ralston’s darkness and his need for independence–as do the voicemails he ignores from his mother and sister, which are played in flashback. His sister reminds the audience that Ralston has Things to Live For. Hell, Ralston even tries to console his mother in advance (when he records his deathbed goodbye with his video cam) by saying things like, “Don’t feel bad about buying me such cheap, crappy mountain climbing equipment Mom … I mean, how were you supposed to know this would happen!” Hehe. What? Apparently it’s easier to use every possible cliche ever of how men and women interact (as a way to reveal information about the hero’s personality and psyche) than it is to, I don’t know, show him interacting with some guys? Have him flashback-interact with Dad? Nope, we get Lost Women in Need, Wedding Dresses, and Mommy Blaming. And I haven’t even gotten to the masturbation scene yet.

[This is your Spoiler Alert.]

I struggled with the masturbation scene. Because it’s a failed masturbation scene. I mean, it’s a scene where masturbation is attempted unsuccessfully. I didn’t like that he took out his video camera and freeze-framed and zoomed in on a woman’s breasts from earlier–as far as I’m concerned, there’s no other way to look at that than as classic Objectification (and dismemberment) of Women. (Also, the audience laughed, and I was taken out of the film yet again.) But at the same time … whoa. Ralston knows he’s about to die. He’s out of water. He’s got no hope of being rescued. Ultimately, masturbation for him is an act of desperation, the desire to feel something that his body has already let go of. Yes–it’s powerful stuff. Watching Ralston’s body betray him shows his imminent physical death.

But it felt too much like The Ultimate Betrayal. As much as I sympathized with Ralston–and Franco is brilliant in this scene–I don’t want to let the film off the hook entirely. I mean, what’s with men and their dicks? If I’m trapped down there, I’m thinking, “A little less masturbation, a little more amputation.” Honestly. The scene played too much like a metaphor for his final loss of power (read: masculinity), as impotence usually does on-screen. In that moment, I no longer identified with the film’s initial overarching theme of hope and possible redemption; I just thought, “Oh man, he can’t get it up it. SNAP.” I guess I’m just wondering if the film really needed to go there …

So, aside from the women “characters” being cliched, pointless, slightly offensive insertions used only to further our understanding of Ralston, 127 Hours is a fabulous film. I’m not even being sarcastic. I’ve never been much of a Franco fan–I mean, apparently he’s teaching a class about himself now?–but this performance is a game-changer for James and me. Boyle certainly showed his directing chops, too; this movie goes places a viewer would never expect–in fact, I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything like it. I cried. I eye-rolled. I looked away (often). And I laughed. Especially at the end of the film, when the woman behind me said, “Wait. You mean that shit was a true story?!”

|

| The King’s Speech: An Intimate, Winning Look into a Powerful Male Relationship |

I live in New York City, and when I went to see the film in Union Square, it had already been nominated for a whopping 12 Academy Awards. It was a packed movie house, and even in the midst of the most diverse locale in America, the audience was almost exclusively older, white couples. To be clear, I liked the film, and I’m not suggesting it needed to broaden its treatment of the King as, say, the British Raj. But if this audience was any indication, most people walked away from The King’s Speech without understanding to whom exactly we’ve been so adeptly ingratiated.

The film is book-ended by two pivotal public speaking engagements for Prince Albert, who later ascends to the throne as King George VI. The film opens in 1925 at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Stadium, and closes in 1939 with a global radio broadcast declaration of war with Germany. To contextualize this time period, in 1925, M.K. Ghandi had recently been released from a two-year prison sentence awarded by order of the British Raj for his galvanizing leadership in the anti-colonialist Indian Independence movement. 1930 saw M.K. Ghandi leading the galvanizing Salt March through an economically crippled India, a strategic moment in sovereignty struggle. As I watched, laughed, and rooted for Bertie to speak with all his might, I couldn’t help but reflect upon the worldwide impact of his every word. It is always worthwhile to qualify any fawning, particularly in a rather segregated western popular culture market. That being said, The King’s Speech is a loveable film framed around acute performance anxiety, something we can all relate to.

It took a solid team led by Director Tom Hooper to create this uniquely intimate period film. Period films can come off stuffy, but here the outdoor shots glint with bracing, misty energy and the indoor shots are defined by palpable, direct-gaze intimacy. Recall the intriguing approach of Elizabeth’s chauffered car creeping along cobblestone streets towards Logue’s home, horse drawn carriages and other period mise-en-scene coming in and out of fog. There was the dewy sunlight of the sculpted garden scene where Bertie, nursing wounds from a scathing run-in with popular brother David (Guy Pearce as King Edward VIII), walked away from Logue in a fit of defensive anger, his sharply outlined shadow trailing him like an afterthought of remorse. Internal shots are palpably and unusually intimate. Take for example, the film’s numerous peeks into Bertie’s mouth, gargling, inadvertently spitting in effort, or full of marbles. There is the stark, dignified honesty of the curling turquoise decay that marks the wall in Logue’s speech therapy room.

Notably, the film tends towards flat, pictorial frames, direct eye gazes, and close-up, slightly de-centered frames. Manohla Dargis, in her New York Times review, bemoaned Hooper’s “unwise” use of the fish-eye lens as a too literal metaphor for Bertie’s life in a fishbowl. But I found the close-ups ultimately supportive of the film’s overall tone. A direct gaze shot of Logue at the head of his family dinner table suitably emphasizes how this very place, from where he is now looking at us, is perhaps the only place where this talented yet under-employed therapist retains a sense of power.

It cannot be said that this film has any meaningful roles for women, who are simply not the focus in this story. No matter how much is written about Helena Bonham Carter’s canny and compassionate Elizabeth, the film boils down to cinematic basics when it comes to women. There are two doting wives (Jennifer Ehle as Myrtle Logue), one frowned upon mistress (Eve Best as Mrs. Wallis Simpson), and three rather doll-like daughters. Aside from a small battle of wills between Bertie and Elizabeth (in which we taste a tiny bit of her wry cunning as the Red Queen in Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland), there is not a hint of nuance for any female role. No, you don’t watch this film to see women shine. Instead, what makes The King’s Speech unique is its tender treatment of a relationship between two men, Logue with his power to heal, and Bertie with his power to rule.

Rarely have I seen such exploration, such daring vulnerability in the portrayal of male relations on the contemporary western cinematic screen. Perhaps being the King of an Empire allows for this intimacy, because regardless of how vulnerable Bertie reveals himself to be, he still rules. The King and his unlicensed speech doctor navigate class differences adeptly, heartbreakingly, on their way to foraging the trust needed for Bertie’s impediment to heal. While Logue is humble, he never concedes honor, and it is this adroit balance that allows us to willingly follow where he may take us, especially when the road is audacious (casually calling him Bertie! making the King cuss and roll about on the floor!). For Bertie’s part, it is painfully evident that he rarely, if ever, had a truly intimate relationship with another man. His father nit-picked and neglected him, his older brother demeans him with ferocious skill, and a stuttering would-be King is born. The awards Colin Firth is racking up for his portrayal of Bertie surely have to do with his ability to embody the process by which a rock of defenses sincerely and helplessly cracks open.

By all pre-Oscar indicators, The King’s Speech is securely in line for recognition at the 83rd Academy Awards ceremony. The question is, what will the film garner stateside, given stiff competition from critically fawned-over flicks like The Social Network and Black Swan?

The King’s Speech swept in five major categories at the UK Oscars, otherwise known as the BAFTA Awards (British Academy of Film and Television Arts). This was a resounding showing despite an arguable snub by the British Film Institutes monthly magazine, Sight and Sound, in their popular top ten poll.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the film hasn’t fared as well stateside, but it’s still getting some shine. Lead actor Colin Firth won a Golden Globe and a SAG Award (Screen Actors Guild), and the film earned another SAG for Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture. If I had to predict, I’d say The King’s Speech will at best win in one major category (that won’t offset the domestic darlings from their perch), such as Best Supporting Actor, and in one or two less high profile awards such as Best Original Score. If you haven’t already seen it, go see it while it’s still in the theater, especially if you know what it’s like to quake a little before a public performance of speech or song. The film’s intimate look at the somatics of sound and breath will get you in the gut, and before you know you’ll be laughing and rooting hard for the King. But do me one favor, just don’t forget who you’re rooting for.

Roopa is finishing her Masters in Cinema Studies at Tisch/NYU, and got her law degree from UC Berkeley in 2003. She loves writing and teaching about the political context of contemporary popular culture, and often blogs at her site, http://politicalpoet.

|

| The Social Network (2010) |

There are two ways to read women in the universe of The Social Network:

1. As unnecessary set dressing, existing solely for the aesthetic and sexual pleasure of men; or

2. As vital to the invention of social networking and, by extension, to the progression of the film’s plot.

The first reading is actually the one I prefer. The truth is, the female characters in The Social Network are so poorly written that it is easy to ignore them entirely. They are relegated to the roles of girlfriends, ex-girlfriends, one-night stands, groupies and lawyers out to destroy Mark Zuckerberg’s empire. None of them are directly involved in the creation of Facebook or any other social networking site – they are the scenery that accompanies the male protagonists (and antagonists) as they go about reinventing human communication. In fact, if you removed the women from the story entirely, nothing would really change.

My fiancé, who also writes movie reviews, likes to refer to this as “superfluous woman syndrome.” He points out the fact that such treatment of women has become a standard film cliché, and I tend to agree. I think that’s why it didn’t take away from my enjoyment of The Social Network. Yes, it’s maddening that so many films lack positive, three-dimensional roles for women, but perhaps there just wasn’t room for women in The Social Network. It’s based on a true story, after all – could it just be that no women played important roles in the real-life creation of Facebook? If that is indeed the case, I can’t fault Aaron Sorkin or David Fincher for leaving three-dimensional women out of the film.

And this brings us to the second potential reading of women in The Social Network. I typically hope that women fill vital roles in movies, but in the case of The Social Network, that reading is incredibly troubling. The film is bookended by Mark Zuckerberg’s relationship with his girlfriend, Erica. The first scene depicts Mark and Erica on a date, during which Mark is particularly rude and dismissive to Erica, and she, deciding she’s had enough of this treatment, dumps him. This leads Mark to write a highly inappropriate blog post about his ex-girlfriend, which leads him to create a website comparing the attractiveness of Harvard co-eds…which ultimately leads him to create Facebook. Which, by extension, means that Mark Zuckerberg created Facebook because his girlfriend broke his heart.

Again, this would be fine, if it was really how Facebook came into being. Except it wasn’t. Mark Zuckerberg has had the same girlfriend since 2003. And this brings us back to the first reading of The Social Network. The fact that no women do anything significant aside from giving Mark Zuckerberg motivational angst doesn’t mean that no women played significant roles in the creation of Facebook, because we already know that the truth has been altered in the transition to celluloid. All it means is that the filmmakers could not think of anything interesting for any woman to do, other than provide the male leads with enough angst to fuel the film’s action. And that’s the most horrifying reading of all.

Carrie Polansky is one of the Editors and Founders of Gender Across Borders. She graduated from Emerson College in 2008 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in Visual and Media Arts (and a minor in Women’s and Gender Studies). Her review of Precious: Based on the Novel Push by Sapphire appeared in last year’s Bitch Flicks’ Best Picture Nominee Review Series. She vows to produce films with much, much better roles for women than the roles in The Social Network.

|

| The Fighter (2010) |

The adage of “Behind every good man is a great woman” is worn out, particularly in the realm of boxing movies. You can reduce the entirety of Rocky to the battered Stallone’s anguished cry of “Adrian!” as he wraps up a brutal fight. We’re meant to believe that what kept him alive was passion, love, a desire to see life through to the closing bell. It’s a hackneyed way of suggesting that though Rocky pounds with his fists, he really leads with his heart. This is the kind of boxing movie that writes itself, and one that doesn’t really need to be seen more than once. Luckily for everyone, David O. Russell’s The Fighter is not that kind of movie. Instead of being a movie about masculine physicality and power, we get a subversive movie about the women that wage real battles outside the ring, the kind of battles aren’t cleanly won.

And they’re right to fear her: with her steely nerve, Alice is as brazen a coach, Mama Rose in the boxing ring, Joey LaMotta in a push-up bra. When Micky goes absent from her immediate purvey, she shows up on his porch with the sisters in tow, posing questions that put him right back in the place of the apologetic son. “What’re you doing, Mickster?” she asks, her eyes all hard with disdain and disappointment. “Who’s gonna look after you?” Alice knows that mother love—and filial obligation—is one of the most powerful weapons she has. “I have done everything, everything I could for you,” she mutters. Her life is bound up in her children, and her coaching mantra is entirely one of maternity. When she catches Dicky sneaking out of a crackhouse, she shakes her head, on the verge of tears, and he has to sing to her like a little boy to pull her back to sanity.

It’s not easy being the son of such a demanding mother, and while Dicky gets to joke his way back into favor, all Micky can do is fight—fight and lose, but fight nonetheless. So it makes sense, given his messed-up family history, that Micky first starts to move out of the nest after falling for Charlene, a local bartender and the first person to call “bullshit” on his family-as-manager situation. (As portrayed by an utterly unglamorous Amy Adams, Charlene is one of the few college-educated characters in the film—due to an athletic scholarship for high-jump.) Charlene’s power in this movie is not as a love interest, but as someone who doesn’t treat Micky like a son or like a brother. She tells him he has to seize control of his career, toss Alice and Dicky off his team, and get serious with a real coach. We think she’s imagining him as a full-grown, self-sufficient man, but she also can’t help but place herself as an equal contender for the managerial job. She gives him a reason to go looking for new management, but she also seats herself decisively by the side of the ring. This is not a woman content to show up after the fight is finished—she is very much an active participant. “You got your confidence and your focus from O’Keefe, and from Sal, and from your father, and from me,” she declares, and there’s not an ounce of hesitation in what she says. It’s thrilling to watch the formerly meek mouse known as Amy Adams get to play someone so fierce.

It’s when the instincts of the protective mother and the defensive girlfriend go up against each other that all hell breaks loose. Alice decides to storm over to Mickey’s house with her daughters in tow, ringing the bell and banging on the door just as Micky and Charlene are doing the nasty. The bell rings and rings, and Charlene, furious at being interrupted, throws on a t-shirt and storms downstairs. Alice pleads with Micky to leave and come back home, but Charlene accuses Alice of allowing her son to get hurt, instead of stepping in and protecting him. In the midst of a boxing movie, what we get is a treatise on how women are the only ones that really know how to fight. Alice calls Charlene a skank, an “MTV Girl” (because clearly all MTV girls are hefting pitches of lager and fending off crude bar patrons), and Charlene lands a solid punch on one of the Eklund sisters. Her fists crunch into the girl’s face, red hair flying wild and legs kicking, and we know that none of these women can be fucked with.

It’s when the instincts of the protective mother and the defensive girlfriend go up against each other that all hell breaks loose. Alice decides to storm over to Mickey’s house with her daughters in tow, ringing the bell and banging on the door just as Micky and Charlene are doing the nasty. The bell rings and rings, and Charlene, furious at being interrupted, throws on a t-shirt and storms downstairs. Alice pleads with Micky to leave and come back home, but Charlene accuses Alice of allowing her son to get hurt, instead of stepping in and protecting him. In the midst of a boxing movie, what we get is a treatise on how women are the only ones that really know how to fight. Alice calls Charlene a skank, an “MTV Girl” (because clearly all MTV girls are hefting pitches of lager and fending off crude bar patrons), and Charlene lands a solid punch on one of the Eklund sisters. Her fists crunch into the girl’s face, red hair flying wild and legs kicking, and we know that none of these women can be fucked with.

Dicky is manic, and Micky is panicked, but it’s the women who are the real pillars of strength. Thus Micky and Dicky are forced to mediate through their female counterparts—Alice, who can’t stand to let her son give up, or Charlene, who forces Dicky into conceding some deeply held delusions. The dual strength of these women are what define the movie, what separates The Fighter from its fellow inspirational tales of athletic triumph, and what catapults it into a movie about athletic effort, and the force of will. And in the movie’s final joyous fight, we still get a triumphant romantic kiss…and it feels anything but hackneyed.

Most of the commentary out there on The Social Network focuses on its awesomeness and front-runner status for this year’s Best Picture Academy Award. Plus, the film won its opening weekend’s box office, even though it’s numbers were lower than anticipated. While it very well may be a brilliantly-made film, one thing we can’t ignore is the film’s women. Other people are talking about the film’s misogyny, too, which raises this question:

Here are some of our findings. If you’ve written about the women of The Social Network, or have read something good that we missed, please leave your links in the comments section.

Rebecca Davis O’Brien’s “The Social Network’s Female Props” @ The Daily Beast:

Complaining about misogyny in modern blockbuster cinema is about as productive as lamenting Facebook’s grip on our society. But what is the state of things if a film that keeps women on the outer circles of male innovation enjoys such critical acclaim; indeed, is heralded as the “defining” story of our age? What are we to do with a great film that makes women look so awful?

Tracy Clark-Flory’s “Female programmers on “The Social Network” @ Salon Broadsheet

But, oh, are there groupies: They aggressively undo belt buckles in bathroom stalls, take bong hits while the boys do their important coding work and rip open their blouses so that coke can be snorted off their flat little tummies. They are useless on the technical and business front, as is made clear in a scene where two groupies look on as Zuckerberg has a sudden revelation and begins barking orders to his all-male team. The doe-eyed coeds ask if there is anything they can do to help out — and the question itself is a punch line. Even a nubile Facebook intern who presumably does have some technical abilities is introduced only to party with Facebook’s smooth-talking president, Sean Parker (played by Justin Timberlake), at a Stanford frat party. The women are trophies for these male history-makers.

Laurie Penny’s “Facebook, capitalism and geek entitlement” @ New Statesman

The only roles for women in this drama are dancing naked on tables at exclusive fraternity clubs, inspiring men to genius by spurning their carnal advances and giving appreciative blowjobs in bathroom stalls. This is no reflection on the personal moral compass of Sorkin, who is no misogynist, but who understands that in rarefied American circles of power and privilege, women are still stage-hands, and objectification is hard currency.

The territory of this modern parable is precisely objectification: not just of women, but of all consumers. In what the film’s promoters describe as a “definitively American ” story of entrepreneurship, Zuckerberg becomes rich because, as a social outsider, he can see the value in reappropriating the social as something that can be monetised. This is what Facebook is about, and ultimately what capitalist realism is about: life as reducible to one giant hot-or-not contest, with adverts.

Irin Carmon’s The Social Network, Where Women Never Have Ideas @ Jezebel

Hollywood’s solution to Facebook’s unsexy creation story was familiar: Add women as sluts, stalkers, or ballbusters. With very few exceptions, girls don’t even know how to properly play video games or get high off a bong, and they’re gold-diggers or humiliating bitches, and they certainly never come up with anything of value on their own. The result is a fictional Harvard as crudely misogynistic as Hollywood — which, thankfully, it actually wasn’t — and a world in which the best a woman can hope for is to have her rejection create as meaningful a legacy.

Melissa Silverstein’s “The Social Network” @ Women and Hollywood

The film depicts a world where women are crazy groupies, there for amusement, to give you blow jobs in bathrooms at parties, and to snort coke off of, but not to be taken seriously. The tech world has long been known as a world that favors guys, just this week twitter was all “atwitter” about a women in tech panel that occurred at the TechCrunch Disrupt event in SF.

I guess that is one reason why it is a perfect movie for Hollywood today. I know there are women doing some seriously important and great jobs in tech, just like I know that there are women doing some seriously important and great jobs in the films business. But we all know that the tech guys are more visible and the movie guys are more visible.

Steven Colbert’s interview with Aaron Sorkin @ The Colbert Report

| The Colbert Report | Mon – Thurs 11:30pm / 10:30c | |||

| Aaron Sorkin | ||||

| www.colbertnation.com | ||||

|

||||

Jennifer Armstrong’s “‘The Social Network’ has a woman problem” @ Entertainment Weekly’s Pop Watch

The Social Network has turned out to be the rare pop cultural phenomenon that is everything we hoped it would be. Smart, riveting, and very much of our time, it provides endless fodder for intellectual dissection and further exploration. The fact that it has become so all-engrossing, however, makes one glaring fact about it all the more disturbing: Its downright appalling depiction of women.

Roxanne Samer’s “Review: The Social Network” @ Gender Across Borders

Previously, I have argued that in some cases representations of sexism and racism can serve as political critiques of the mistreatment they depict. One could claim that Zuckerberg and his peers’ objectifying of women and fetishization of Asian women in particular is presented in the film as in poor taste. The film is by no means casting Zuckerberg, never mind Parker, as an innocent angel. But in the end one must ask: are these trysts etc. depicted as deplorable or as typical and tolerable 20-something boy behavior? My intuition says it’s the latter.

JOS’ “Social Network sexism” @ Feministing

The film follows an interesting pattern I’ve noticed in other work by contemporary male filmmakers (Inception as an example) – it offers compelling insight into sexism while also displaying a sexist perspective in its storytelling.

Cynthia Fuchs’ “‘The Social Network’: Fincher and Sorkin’s Story of Obsession” @ Pop Matters

Based on Ben Mezrich’s 2009 book, The Accidental Billionaires, and scripted by Aaron Sorkin, the film is already renowned for its breakneck dialogue (especially when Mark speaks, condescendingly and oh-so-cruelly). However fictionalized that dialogue might be (the book imagines conversations as it recounts events mainly from Eduardo’s perspective, and includes luridish party and sex scenes), it represents here an attitude that makes its own political and cultural point, that men and boys in privileged positions tend to see the world in ways that benefits them, that reinforces their privilege.

Jenni Miller’s “‘The Social Network’ and Sexism: Does the Film Treat Women Unfairly?” @ Cinematical

We’re given a trio of wholly unreliable narrators who do see women as props and prizes and ugly feminists out to get them. They’re emblematic of all the things that the fictional Mark Zuckerberg wants and feels are out of his reach, like the Harvard social clubs. Even Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield) questions whether or not Zuckerberg’s screwing him over all boils down to the fact that Saverin got into one of Harvard’s fancy clubs where WASPs cheer on half-naked women making out with each other.

David Ehrlich’s “5 Reasons Why ‘The Social Network’ Does Not Define This Generation” also @ Cinematical

5. It’s a film about men in a generation that’s also about women (I hope).

Alison Willmore’s “The (Homo)Social Network” @ IFC

The suggestion that Aaron Sorkin and David Fincher had an obligation to insert a token “strong lady” character in order to make their film more demographically friendly or underline how their own intentions are separate from their characters is condescending to audiences. The film world still leans incredibly toward male perspectives, male characters and male audiences, and the way to fix that is by supporting and encouraging women making and working in movies, not by implying the need for an artificial quota of “go girl”ness.

Dana Stevens’ “Is the Facebook movie sexist?” @ Slate

The Social Network presents an odd paradox in its vision of the war between the sexes (which, like all the conflict in this movie, is a real war, brutal and unattenuated). It’s smarter about the way women circulate as objects of male competition, predation, and fantasy than it is about the motivations of individual female characters. The film’s “women problem” doesn’t lie in the fact that many of the women in it (with the exception of Erica Albright and the lawyer played by Rashida Jones) are shallow, self-serving jerks—so are most of the men. But any film capable of putting on-screen as complex and fascinating a jerk as Jesse Eisenberg’s Mark Zuckerberg should be smart enough to do the same for the ladies.

Discussing the sexual politics of the film, Karina Longworth, of The Village Voice, says

When the band turns on Cherie for submitting to a solo soft-core photo shoot, it’s because Joan understands that unless they set the terms of their own sexual empowerment, and its commoditization, then what’s really happening is exploitation. “You could say ‘No,’ ” she tells Cherie. It’s a shock to the blonde; it’s also the thesis of the film.