First off, the TV series Battlestar Galactica just plain rules. It’s exciting, dramatic, beautifully shot, has a racially diverse cast, and places many women in positions of power. Let’s take a minute to consider the fact that the benevolent commander of the military protecting the human race from extinction is portrayed by a Mexican American (Commander William Adama/Edward James Olmos), and the President of the Colonies is a woman (Laura Roslin). Bravo! My favorite aspect of the show, though, is the way it tackles complex ethical dilemmas. Issues of race (the Cylons as stand-ins for racial Others), women’s issues (rape, abortion, breast cancer), philosophical/scientific issues (religious extremism, mysticism, whether or not some species “deserve to survive,” what makes one “human,” evolution), and post-colonial issues (the Cylons as stand-ins for an oppressed race that genocidally revolts against its oppressors).

One of the complex ethical dilemmas the show took on was the implied question, “What would’ve happened to the surviving human race if they hadn’t decided to find Earth? What if they’d chosen a path of vengeance instead?” This idea is explored in the Season 2 episodes “Pegasus” and the two-part “Resurrection Ship” as well as in the feature-length film Battlestar Galactica: Razor. These episodes and companion film follow the path of the Battlestar Pegasus and its actions following the Cylon attack that obliterates the Colonies. Though the “what if” question is ostensibly the premise of this arc, in reality, they become a scathing, anti-feminist critique of women with military authority.

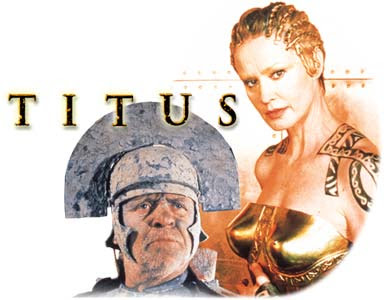

Meet Admiral Helena Cain, commanding officer of the Pegasus.

It’s important to note that in the original series, Commander Cain was portrayed by a man whom Adama outranked and had a tendency to be insubordinate. In the reboot, Admiral Cain is a lesbian who outranks Adama and is a very strict interpreter of military law. Therefore, we must view the changes made to the character as deliberate.

Throughout the Pegasus arc, we learn that, when the chips are down, Cain develops a propensity for brutality. After the Cylon attack, Cain gives a speech to her crew with the poignant line, “War is our imperative, so we will fight.” She sees revenge-based guerrilla warfare against the Cylons as the only path for the surviving members of humanity, and she will brook no insubordination, no questioning of her authority, and no hints of mutiny. In one of the most shocking acts in the entire series, Cain disarms her good friend and XO, Jurgen Belzen, before shooting him for refusing to follow an order, which ends up costing the lives of a significant portion of the crew.

Not only that, but the Pegasus encounters a civilian fleet that Cain orders her soldiers strip of any useful resources. This includes their FTL drives, which allow them to travel at faster than light speed, as well as any potentially valuable passengers who can be drafted to work aboard the Pegasus. When it’s all said and done, Cain leaves 15 civilian ships helpless and adrift in space after killing 10 family members who resisted her passenger transport order. Where Adama is a commander who values each and every human life, frequently risking the lives of the many to save a scant handful of his people, Cain takes a hard-line approach, valuing her mission of Cylon destruction over individual human losses. In a way, she is a caricature of military masculinity, overcompensating for being a woman by allowing no compassion to enter her decision-making. Her sense of authority is so tyrannically absolute that she becomes inhuman, ruthless, and the villain of the arc.

The most striking display of Cain’s brutality is the way she deals with Gina Inviere, her lover who is exposed as a Cylon (model 6). The Cain/Inviere relationship is the only lesbian romance shown or developed in the entire series (despite the fact that some of us believe Starbuck would’ve been a lot happier had she come out of the closet). I’d even go so far as to say that portraying Cain as a lesbian is yet another example of her hyper-masculinization. She’s trying so hard to shun her femininity and embody masculinity that she even likes to sleep with women, which is an exceedingly problematic depiction of lesbianism.

When Inviere’s status as a Cylon spy is discovered, Cain gives yet another of the series most chilling commands, “Interrogate our Cylon prisoner. Find out everything it knows, and since it’s so adept at mimicking human feeling, I’m assuming that its software is vulnerable to them as well, so pain, degradation, fear, shame. I want you to really test its limits. Be as creative as you feel the need to be.” Inviere is cruelly and mercilessly beaten, starved, and forced to lay in her own waste and filth, but worst of all, she is raped repeatedly. In an act that encourages the excessive, brute side of masculinity, Cain has allowed her crewmembers to line up and take turns gang raping Inviere. Even the crewmembers of Galactica who despise Cylons are appalled to learn this.

Cain’s treatment of Inviere is not that of a commander dealing with an enemy soldier and spy. Cain is punishing Inviere for betrayal as only an ex-lover and scorned woman can.

Certainly, Cain has a legitimate hatred of the Cylons, and her pursuit and harassment of them was initiated before she learned of Inviere’s betrayal. However, Cain’s death scene poignantly recontextualizes her actions and motivations. Baltar allows Inviere to escape custody, giving her a gun. Of course, she sneaks into Cain’s quarters to take revenge on her tormentor. The exchange between the women is revealing, as Inviere holds a gun to the defenseless but still defiant Cain.

When Inviere tells Cain, “You’re not my type,” the camera flashes to Cain briefly before we hear the shot that kills her, and the look on her face is one of terrible anguish. This moment of pain and weakness makes the viewer question whether all her choices after learning of Inviere’s betrayal are those of an overly emotional woman whose heart has been broken, causing her to behave recklessly. She is, in effect, lashing out at the Cylons because one of their agents preyed upon her frailty as a woman in love, and the brutality with which she executes these attacks strives to bury that weakness. This reading, along with the reading of Cain as overcompensating for her femaleness by being excessively masculine in her military command, form a paradox. The show asserts that lesbian military officers are simultaneously too masculine and too feminine.

The show presents Roslin’s form of authority as more in-line with feminine capabilities. Roslin, as President of the Colonies, is a very maternal role. She is trying to ensure all of her people/her children survive. After the Cylon attack, it is her words of reason that turn Adama from the path of vengeance toward the search for Earth. Though she is dying of breast cancer (a very female-targeted disease), she sacrifices every last bit of comfort to save the human race, martyring herself. She often defers to Adama’s military command, and she very rarely resorts to violence as she finds it morally repugnant. As a fellow woman, though, Roslin recognizes the grave threat Cain poses to the fleet and for the continuation of the human race. Roslin reacts like a cornered mother, insisting that Cain’s assassination is the only solution. These two examples of female authority cannot co-exist. The series asserts that Roslin’s brand of power is strong and righteous while Cain should be put down like a rabid, dangerous animal that can’t be controlled.

The legacy of Cain is another theme upon which the show meditates. In Razor, Admiral Cain’s mentorship of Kendra Shaw is a foil for Bill Adama and Starbuck’s mentor relationship. Cain exclusively mentors young, attractive women (first Shaw then Starbuck), subtly positioning her as something of a sexual predator. Shaw and Starbuck are both their commanding officers’ favorites; they’re both fiercely loyal, both of them are frequently insubordinate and, naturally, dislike each other. When both commanders are given similar raw material with endless potential in these young officers, what happens? Cain turns Shaw into a cold civilian murderer and drug addict whose loyalty resembles that of a dog rather than that of an intelligent, independent woman. On the other hand, Adama’s firm, but understanding, hand shapes Starbuck into an amazing pilot, brilliant tactician, and a leader whose persistence leads her people to Earth. Shaw is only allowed redemption with her selfless death under the command of Bill and Apollo Adama.

Cain’s “razor” philosophy insists that in order to survive, we must put aside our human delicacies and fragility in place of strength and decisiveness: “Sometimes we have to do things that we never thought we were capable of…setting aside your fear, setting aside your hesitation and even your revulsion, every natural inhibition that, during battle, can mean the difference between life and death. When you can become this [shows knife blade] for as long as you have to be, then you’re a razor. This war is forcing us all to become razors because if we don’t, we don’t survive, and then we don’t have the luxury of becoming simply human again.” This is very much a PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) survivor coping mechanism. Survival becomes the only goal, and emotions, weakness, and empathy become liabilities. Adama, on the other hand, insists on a full life with honor, dignity, companionship, and compassion. These distinctly human traits, he believes, set his people apart from the Cylons, and survival doesn’t mean anything without the preservation of these qualities. Though some lip service is paid to the notions that Cain’s command decisions and her philosophy weren’t technically wrong and that the fleet was safer with her in charge, the show paints (and majority of viewers see) her as one of the most evil characters ever represented on Battlestar Galactica.

Perhaps the most damning foil used to compare Cain’s command to that of Adama is their treatment of their Cylon prisoners. When Inviere is exposed as a Cylon in CIC, she kills people, but when she turns her gun to Cain, Inviere hesitates and clearly does not want to kill her lover, though it is her duty as a soldier. Eventually, though, she kills Cain, and because the horrors inflicted on her are so unimaginable, Inviere wishes to permanently die outside the range of a resurrection ship. Cain’s unspeakable torture of Inviere has confirmed every fear, every bigotry, and every hatred Cylons have for humans. Yes, Adama’s relations with Cylons are, at times, rocky, but the Sharon/Athena model on-board Galactica during the Pegasus arc is treated humanely, her half-human/half-Cylon child is brought to term, her expertise and wisdom consulted, and her information is valued until she is no longer a prisoner, but a crewmember. This collaboration, this peace, this commingling and hybridization of the human and Cylon races is the true key to survival. If Cain continued her command of the fleet, that fleet, along with the entire human race, would have perished.

Though Cain is a charismatic figure who viewers love to hate, I’m troubled by how thoroughly irredeemable her character is. She embodies every fear and stereotype popularly held about women in power, i.e. that they’ll try to be men, that they’ll be too weak and womanish to make rational decisions, that those decisions will come from a place of heightened emotions, and that, ultimately, they’ll harm those they were charged with safeguarding. The sparseness of queer character representations on the series is also troubling, and to have the lesbian admiral be such a “butch stone cold bitch” makes me question the series’ true progressiveness with regards to women in power, especially queer women in power. The series succeeds on many levels, and I applaud them for tackling complex moral issues. I also applaud them for depicting the highest ranking military officer alive as a strong lesbian. How much richness and complexity, though, would have been added to Cain’s story if she’d been portrayed with more compassion, her choices less black and white, her struggles and reactions more defensible? How much more interesting would the Pegasus arc have been if Adama and Roslin still chose to assassinate Cain despite her representation as a flawed woman trying to do what was best? Hell, what if Cain had lived, and the Adama/Roslin regime had been toppled? What if Cain and Adama truly had to work together in a long-term, meaningful way? In the words of Bill Adama, “I’d like to sell tickets to that dance.”

Amanda Rodriguez is an environmental activist living in Asheville, North Carolina. She holds a BA from Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio and an MFA in fiction writing from Queens University in Charlotte, NC. She writes all about food and drinking games on her blog Booze and Baking. Fun fact: while living in Kyoto, Japan, her house was attacked by monkeys.