This guest post by Natalie Wilson previously appeared in a shorter version at the Ms. Blog and is cross-posted with permission.

WARNING: THIS PIECE CONTAINS SPOILERS!

Gone Girl has been called misogynist, an amalgamation of negative stereotypes of women, a text that perpetuates rape culture, and a narrative that fuels Men’s Rights Acivtists’ ugly depiction of the gender equality feminists are trying to achieve.

Putting the talent of the author aside – because I do think Gillian Flynn is an incredible writer – I want to address this feminist ire directed at Gone Girl.

To an extent, I agree with it. Yet, what is missing from the discussion is a focus on privilege.

Amy Elliot Dunne, the protagonist of Gone Girl, is white, wealthy, heterosexual, and conventionally attractive (many privileges which her creator, Gillian Flynn, shares).

Yes, Amy is a female, but she is an EXCESSIVELY privileged one, so privileged, in fact, that she has the necessary funds, skills, know-how, and spare time to concoct a near iron-clad story in which she convinces the media, the law, her community, and her family that she has been raped, abused by her husband, kidnapped, imprisoned, and possibly murdered.

Flynn, even given the worldwide success of her writing, is, I would guess, not nearly as privileged as Amy. Plus, if details at the author’s website are correct, she worked odd jobs throughout high school; Amy is not the type of female that had to work in high school, and especially not at anything where she would be made to dress up as a cone of yogurt.

In addition to her privilege, is Amy in fact a compilation of the evils MRAs spout on about in relation to “strong” women? In ways, yes. But this is just it – she is able to be strong – and, yes, to be evil – because she has the privilege to do so. As the saying goes, idle hands make the devil’s work.

Amy is narcissistic, vain, and shallow – and has enough time on her hands to fill her calendar with carefully labeled, color-coded post-its with details of her murder plot. And, once the plot is set in motion, handily has secured enough cash to buy a car, a new wardrobe, and keep her going for who knows how long. When that falls through, there is the very rich former boyfriend Dezi, who will put her up in his “lakehouse” – a spare house that makes many mansions look shabby.

Yes. This is fiction. Yes, it’s a dark, twisted, mystery. It is obviously meant to be. The author herself made it clear that she “wanted to write about the violence of women” after her first book, Sharp Objects. And this is not a problem – not at all – but what is vexing with Gone Girl is at the heart of its narrative is a woman that falsely accuses several men of rape and assault – and tries to frame one of them for murder. This story is a fiction. But rape and assault are at epidemic levels in our society – along with the horrible statistics is a pervasive narrative often called “blaming the victim.” At the heart of this narrative is the myth that females lie about rape. Not once in a blue moon. But often.

This is not what I want to focus on though – what I want to focus on is how privilege allows the fictional Amy to get away with all the atrocities she commits. If she “cried rape” (as MRAs and the media often suggest women do), would she be as readily believed if she were a woman of color? What if she were a prostitute? What if she committed murder and tried to convince the cops of her innocence via mere words? Would she be believed if she were, say, a young Black male? If she accused her partner of physical abuse and adultery would she become America’s media darling if she were not cisgender?

The story of Kalief Browder, featured in The New Yorker, who served three years at Ryker’s Island, most of it in solitary confinement without trial before he was deemed innocent; of Renisha McBride; of Ferguson; is proof that innocence does not mean much for people of color in a society that frames those with non-white skin as born guilty (to borrow Dorothy Roberts claim made in her classic Killing the Black Body).

Gone Girl is not making a critique of privilege though, nor of how Amy’s whiteness and wealth – at least in ways – puts her above the law. Instead, Amy’s ability to frame others for crimes they did not commit and become America’s media darling has been acclaimed as a wonderfully concocted mystery by a talented author. As for Amy’s ability to pull off her fictive story within a story in the novel and the film adapation, this ability is never overtly linked to her privilege – unless you count the fact the film nods toward how wealthy she is, given her cat has its own bedroom. Rather, her success at framing others is presented as a very well-planned revenge plot carried out by a very smart, very malicious woman.

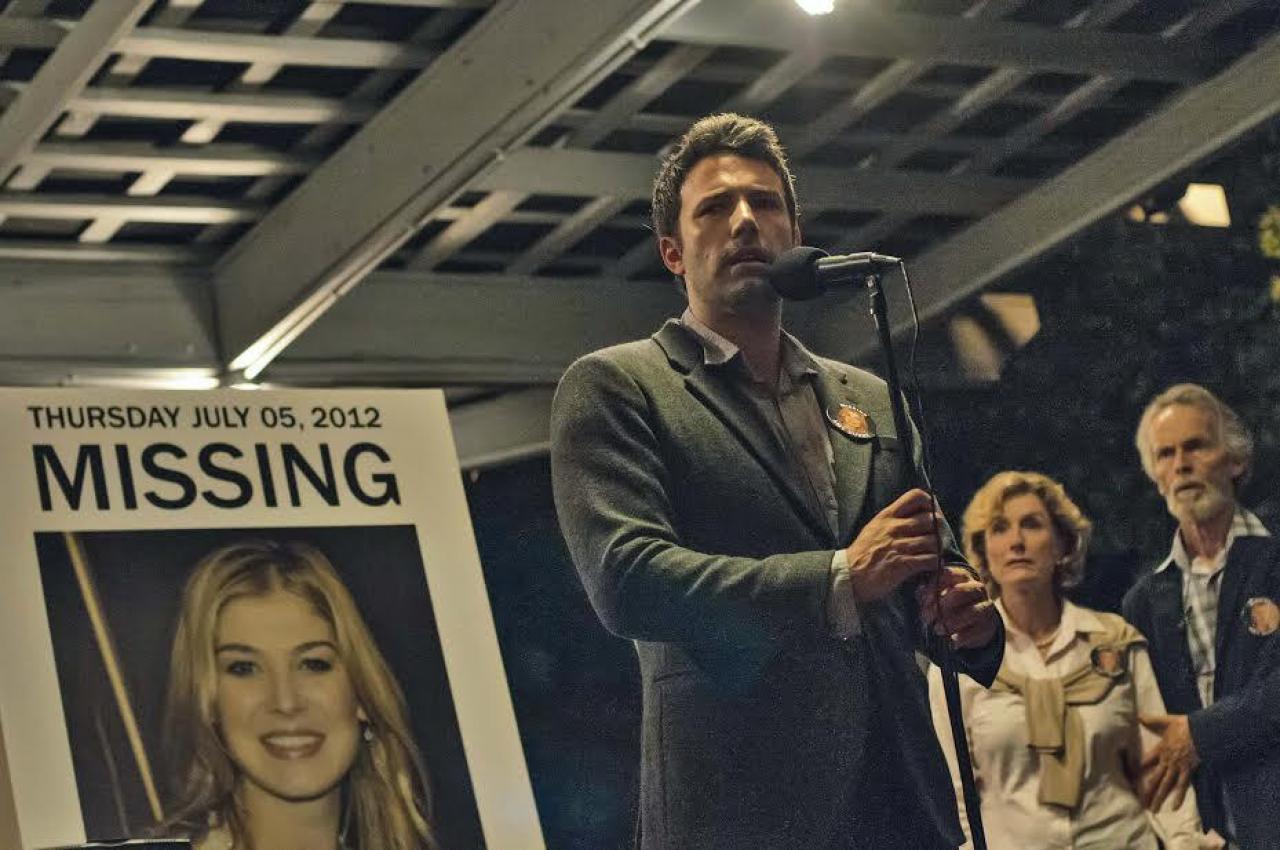

Admittedly, there are things the story does well in terms of critiquing societal problems. A key area in this regard is the portrayal of the media. As with the novel, the film delves into the media circus, giving us talking heads that spin hypotheses about Amy’s whereabouts and who is to blame for her disappearance – hypotheses that quickly lead to the narrative Amy intended: that her husband Nick is guilty, and she is the innocent, abused spouse all America should be routing (and praying) for.

Amy clearly knows how to play straight into the hands of the of “The Ellen Abbot Show” – a fictionalized version of the likes of Nancy Grace. Amy notes, while concocting her plan, that “America loves pregnant women,” and, indeed, Ellen plays up Amy’s pregnancy to garner sympathy for her – and ire for her husband Nick. However, had Amy been a pregnant Latina, or working class, or a single woman, would she still be framed in this way by the real Ellen Abbots of the world? Doubtful.

In fact, if Amy’s accusations of rape against not one, but three men, were to be reported in the real world media, it is likely she would blamed, interrogated, and have her reputation besmirched, especially if she lacked many of the privileges Amy’s character has. As noted in “Gone Girl and the Specter of Feminism,”

“Our society makes real-life survivors of rape into villains every single day. We assume ulterior motives. We invade and question their sexual history as if it’s relevant. We make rape survivors into whores and sluts, into evil, evil women who are only out to hurt and punish men. And that’s if we don’t ignore them altogether, or if they can summon the courage to report the rape at all.”

And though only 2 to 8 percent of reported rapes are determined to be unfounded, it is, as #2 reports, a “norm of the media to question the authenticity of rape victims that dare to step forward and seek justice.”

In the film, Tanner Bolt , the big-shot lawyer defending Nick, is portrayed as particularly media savvy. He says of Amy, for example, that “she is telling the perfect story.” And though his race is not highlighted as a factor, his know-how of the media and the key role public perception plays can be read as shaping the story he tells the world in public appearances.

Tanner advises Nick to do the same, telling him, “This case is about what people think of you,” and emphasizes the need for a huge re-alignment of public perception. Tanner knows this, and Nick should (especially given his former work as a journalist). Read through the lens of race, however (a lens, let me emphasize, the narrative itself does NOT interrogate), one can argue Tanner has to be more savvy than Nick and that Nick is allowed to live in a privilege bubble, one that leads him to assume people are going to believe him.

What people think of Amy – and Nick – is largely determined by their privilege. They live in a huge house, she is a “housewife,” they are both former writers, they are attractive, white, heterosexual, and have the requisite pet – as well as aspirations – on Nick’s part at least – to have children. They are the picture-perfect American couple.

But, this image is a fiction. And the fact the story plays around this fictive construct of what perfection is – and what a perfect marriage is – is one of its most intriguing features. Amy’s diary, a mixture of truth and fiction, is key here. In one telling scene, Detective Boney (my favorite character by far, perhaps as she has the most feminist gumption) goes through Amy’s diary, now being used as police evidence, and asks Nick what is true and what is fiction. The mixture of lies and truth within the diary, and within the entire narrative, make it hard to discern any reliability.

As argued in “The Misogynistic Portrayal of Villainy in Gone Girl,” Amy makes a magnificent unreliable narrator. Sadly though, she is believed – by the media, by the community, even by us, the audience.

If only her believability was tied to her privilege, Flynn could have had a narrative that did something feminists could applaud – a narrative that pulled back the sham of “perfect femininity” and showed the ugly undersides of unfair societal dictates.

Instead, Flynn gives us a character that shares her own privileges – and her own penchant for spinning fictions – rather than one who lays bare the injustices that make the likes of Ellen Abbott believe her, that have lawyers running to defend Nick pro bono, that result in a media machine feeding off this one tragedy while ignoring wider injustices – injustice the camera actually lingers on at the start of the film, making the Missouri of Gone Girl remind one of the Detroit featured in Michael Moore’s Roger and Me.

While the narrative condemns what director David Fincher calls the “tragedy vampirism” of the media, it never takes the next step of pointing out how the poverty and homelessness of the community in which the story takes place plays a role in why Amy becomes a media darling and allows her husband to plausibly suggest the “homeless” are to blame for Amy’s disappearance.

The narrative also never takes any step toward addressing the reality of widespread sexual violence and domestic abuse, instead using this device as just one more piece of grist for its suspenseful, plot-twisting mystery.

In one scene, Amy creates the “proof” of her rapes via thrusting a wine bottle inside herself as she icily gazes in the mirror (a scene also in the book). This comes after we learn she has destroyed the life of a completely innocent man by also framing him for rape, merely because he lost interest in her. And, in the most fraudulent, unbelievable plot point, this man tells us he was about to be put away for 30 years on a first degree felony. Guess how often rapists are put away for 30 years? Not often.

So, yes, Amy is a villain, some suggest a sociopath, but I heartily disagree that her horribleness could only come from a “female mind” – which is exactly what the actress who plays her – Rosamund Pike – claims, that “the way her brain works is purely female.”

Instead, Amy’s villainy, and the fact she gets away with it, can be linked to her substantial wealth, her Ivy League schooling, her full immersion into the culture of “cool girls” and personality quizzes and, perhaps most of all, her sense of entitlement, revealed particularly in the way she expects to be treated, especially by Nick. In a key passage from the novel (also used in the film), Amy embodies the faux-feminism that defines her character, condemning constricting expectations of femininity on the one hand, but, on the other, hinting at the narcissistic darkside of her anger:

“I hated Nick for being surprised when I became me. I hated him for not knowing it had to end, for truly believing he had married this creature, this figment of the imagination of a million masturbatory men, semen-fingered and self-satisfied. He truly seemed astonished when I asked him to listen to me. He couldn’t believe I didn’t love wax-stripping my pussy raw and blowing him on request. That I did mind when he didn’t show up for drinks with my friends… Can you imagine, finally showing your true self to your spouse, your soul mate, and having him not like you?

In ways, we want to applaud Amy for condemning the “cool girl” and demanding females deserve to be listened to – as this seems a feminist message. But, ultimately, Amy is far more like Ann Coulter than Amy Poehler.

Though some might argue Amy is fully aware of and even using her privilege, I disagree. She is aware of being attractive, wealthy, and powerful, yes, but not any feminist way that questions or denounces or even deliberately deploys her privilege. One of the most telling parts of the narrative to display this is in her interactions with Greta, a working class character Amy assumes to be stupid and inept. Greta sees through Amy’s disguises though, and craftily separates her from her wad of cash (which is when Amy is forced to call on Desi to rescue her). The stark difference in the scope of their crimes can be linked to privilege – Amy’s excess verses Greta’s lack. Their experiences and attitudes toward violence are also telling, Greta is familiar with how common male violence against women is, where Amy is not – the violence she accuses men of is actually violence her privilege has protected her from. This is not to say priviledged women never experience violence – but Amy does not, at least not physical violence. Though this strand of the narrative has much feminist potential, the narrative overall does not offer a feminist critique of privilege, let alone violence.

Further, as argued in a post at Interrogating Media, there is a discernible backhanded attitude towards feminism littered throughout the novel. Amy condemns post-feminist men afraid of sexual roughness, for example. But, more than actual comments from Amy, there is a sort of post-feminist cheerleading in the narrative, one that is in keeping with Flynn’s discussion of why she is drawn to writing about the violence of women::

“Isn’t it time to acknowledge the ugly side? I’ve grown quite weary of the spunky heroines, brave rape victims, soul-searching fashionistas that stock so many books. I particularly mourn the lack of female villains — good, potent female villains. Not ill-tempered women who scheme about landing good men and better shoes (as if we had nothing more interesting to war over), not chilly WASP mothers (emotionally distant isn’t necessarily evil), not soapy vixens (merely bitchy doesn’t qualify either). I’m talking violent, wicked women. Scary women. Don’t tell me you don’t know some. The point is, women have spent so many years girl-powering ourselves — to the point of almost parodic encouragement — we’ve left no room to acknowledge our dark side.”

This passage seems to come from within a privilege bubble – one that allows the author to suggest that “fashionistas” or “WASP mothers” or “soapy vixens” – and of course “brave rape victims” – are rather dreary and boring, and that what is needed is to do away with this annoying “girl powering” so we can fill libraries with stories of generations of brutal women (something Flynn seems to envy about male stories). And, don’t get me wrong, like Flynn, I agree we need wicked queens and evil stepmothers and villainous women. It is her reasoning I don’t agree with, that “women like to read about murderous mothers and lost little girls because it’s our only mainstream outlet to even begin discussing violence on a personal level.” Hello? Gillian? Have you heard of this little thing called feminism? Perhaps the phrase “the personal is political” rings a bell?

You see, Flynn’s version of “girl-powering” feminism leaves out actual feminism. Like the stuff of an Ann Coulter dream, it points a finger at Amy, a “girl who has it all” and says, “look at what that women’s lib stuff has wrought!” What it does not point a finger at, not even give a quick passing glance, is those working in sweat shops to make the shoes the “fashionista” covets, the thousands of rapes that go unreported, not due to lack of bravery, but to do the complicated realities of living in a rape culture, the girls who don’t have access to the “parodic encouragement” of any sort of girl-power because they are poor, they are undocumented, or, to use Flynn’s fictive idea, they are nothing like the “Amazing Amys” of the world.

To be clear, I am not suggesting that all narratives need to pack a social justice punch. However, given that Flynn’s novel explores an extremely hot button issue, and created quite the intense feminist debate, it seems odd Flynn never directly addresses the key critique lobbied at Gone Girl, but instead made widely publicized claims the ending of Gone Girl would be changed in the film adaptation–suggesting the changes to the narrative would reframe the very things that angered readers. Though the screenplay is altered from the book, the ending remains the same overall – Amy is not arrested or even blamed – instead, she has manipulated Nick into staying with her and keeping mum about her guilt by impregnating herself with some of his semen she handily stored away. Ah, the privilege of access to sperm banks!

Such tales are not by any means unique in Hollywood – nor are they bad per se. Rather, Flynn’s keenness to defend her work while naming herself a feminist seems off somehow – at least – what seems missing – is a recognition of her own partial, and very privileged, viewpoint. Some women do in fact have to discuss and think about violence all the time in order to survive, not to write bestselling novels. And I want her to keep writing – she is a great writer – but it would be wonderful if at some point she could address – specifically – some of the realities of the rape culture of our society in an interview or public appearance. Not addressing feminism is fine, but to do so in the vein of being so burnt out on “spunky heroines” and “brave rape victims”? Well, that doesn’t sit so well with this feminist.

Perhaps the “parodic encouragement” Flynn refers to as defining feminism is her experience of feminism. Maybe this is partly what fueled the plot point in Gone Girl wherein Amy’s parents made their fortune via “Amazing Amy” books – a series whose main character is much like the real Amy, but better. In a sense, these books are parodying Amy’s life and encouraging her to be more amazing. A woman who has and does it all. A real go getter. This fact serves as an explanation as to why Amy “has never really felt like a person, but a product” (Gone Girl).

But, again, the story falls short of condemning this type of “you go girl” faux-feminism or the notion women can (and should) have it all. It also is not critical of celebrity, fame, and fortune – even though the fortune of Amy’s family comes at the expense of her happiness and sanity. Yes, at one point Amy notes that her parents exploited her childhood and she does seem bitter about this. But this exploitation, from parents she interestingly defines as feminist, is partly what leads to her ability to constantly be playing at being Amy – to live the role of cool girl, good wife, battered wife, and so on. We are not instructed to condemn Amy’s parents exploitation of her – instead we are encouraged to be angry at her parents for mismanaging their money and having to borrow from her trust fund – leaving poor Amy to survive in a Missouri mansion rather than a Manhatten brownstone.

Though much has been written about Flynn’s comments about feminism, her portrayal of women, and her writing, I have not come across her ever mentioning privilege being something she was interested in exploring, even though her characters and her own discussions of why she chooses the focus matter she does drip with privilege. Flynn comes from a privileged background herself, and perhaps this partly explains Gone Girl’s failure to own up to the role Amy’s privilege plays in her “success” in any overt way. Who knows. What I do know is this: not addressing Amy’s privilege directly – and Nick’s, and Dezi’s and Margot’s – has the effect of making the novel seem to be – as argued in the “Gone Girl and the Specter of Feminism,” a piece that serves as a “crystallization of a thousand misogynist myths and fears about female behavior” as if we had “strapped a bunch of Men’s Rights Advocates to beds and downloaded their nightmares.”

In The Guardian piece, “Gillian Flynn on her bestseller Gone Girl and accusations of misogyny”, Oliver Burkeman writes “This is a recurring theme in Flynn’s life: the psychological bungee-jump that permits an author to plunge into barbarity precisely because she’s securely moored in its opposite.” Detailing how Flynn locks herself away in her writing basement for hours, Burkeman notes that “In the early afternoons, she surfaces from the gloom into daylight, to play with her son for an hour or two.” Then, in Flynn’s own words, “It’s back down through the basement again, to write about murder.” Ah, the joys of a post-feminist life!

So, to wrap up this privileged take on Gone Girl: is it a good film? Yes and no. Fincher is great director and Flynn is a great writer – they both tell dark stories well. The movie is compelling and Pike is great as Amy, as is Kim Dickens as Detective Boney, the most feminist character of the film and the one I would most like to see a spinoff series about!

It is good as a film, but it is not a feminist film.

As Esther Bergdahl asks rhetorically in her post, “Is a film feminist if a female character vindicates every men’s rights activist on Reddit?” Of course not. But, just as obviously, this doesn’t mean feminists shouldn’t see it – and discuss it – in fact, just the opposite.

Natalie Wilson, PhD is a literature and women’s studies scholar, blogger, and author. She teaches at Cal State San Marcos and specializes in areas of gender studies, feminism, feminist theory, girl studies, militarism, body studies, boy culture and masculinity, contemporary literature, and popular culture. She is author of the blogs Professor, what if …? and Seduced by Twilight. She is a proud feminist mom of two feminist kids (one daughter, one son) and is an admitted pop-culture junkie. Her favorite food is chocolate.