This guest post written by Stacia Kissick Jones is part of our theme week on Bad Mothers.

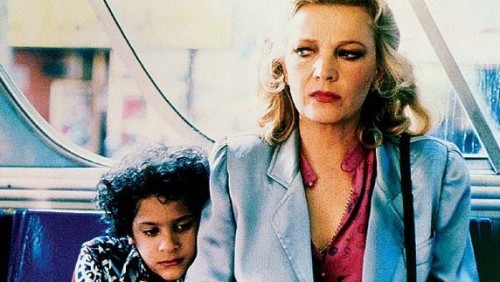

“A mother’s love leads to murder!” announced advertisements for Mildred Pierce (1945), the box-office smash that was Hollywood superstar Joan Crawford’s comeback vehicle. The world had changed in the two years Crawford had spent away from the silver screen; her final film with MGM had been released during the height of World War II, while Mildred Pierce wasn’t released until well after VJ Day. Crawford’s career portraying strong women seemed, on the surface, the exact thing that would make her perfect as Mildred, a divorced mother of two who worked hard at both love and her career. In the post-war climate, however, independent women were seen as a threat, and the American media was encouraging women to leave the jobs they had held during the war and return to the domestic sphere.

In Woman’s Place: The Absent Family of Film Noir, Sylvia Harvey notes that the reaction to the wartime change in traditional gender roles was often expressed in the “underlying sense of horror and uncertainty in film noir,” and that Mildred Pierce, “woman of the world, woman of business, and only secondarily a mother, is a good example of [the] disruption and displacement of the values of family life.” It’s true that Mildred Pierce is commonly seen as an early example of Hollywood’s move toward portraying self-reliant women as disruptive, though there is hardly a consensus on whether the film means to be a cautionary tale against the subversion of traditional gender roles, or whether the movie, mostly through its sympathies with Mildred, slyly expands the boundaries of those gender roles.

When Mildred Pierce opens, Mildred is safely ensconced in the kitchen, pretty in her apron and baking apple pies. But as we soon learn, her baking provides the family’s sole income, as her husband Bert (Bruce Bennett) has no job and no prospects. It seems innocuous enough to our modern eyes, even quaint, but in 1945 the fact that Mildred was turning the domestic world of the kitchen into the social world of business was a real threat. Later, when she opens her own restaurant, she is giving her domesticity to anyone who will pay for it, not reserving it for her husband and kids, making her even more volatile and dangerous.

But long before Mildred even thinks about opening a restaurant, Bert seems to instinctually understand that Mildred’s determination to provide for her family is a threat. He’s sore about that, but about life in general, too, and as Mildred insists their daughters Veda (Ann Blyth) and Kay (Jo Ann Marlowe) are the most important things in her life, Bert’s insecurities flare. He’s certain that piano lessons are spoiling his daughters; Mildred is certain he has taken up with the widow Mrs. Biederhof (Lee Patrick). Mildred has had enough and tells him so. He leaves, not stopping to tell his daughters goodbye.

Teenaged Veda, preternaturally cool and aloof, is unconcerned about her father’s disappearance. She’s a snob, really, and in the James M. Cain novel on which the film is based, much of her attitude is explained by the fact that Mildred actively encouraged Veda’s haughtiness, believing it to be a sign that her daughter was a superior individual. Similarly, Bert had once been rich and had no desire to work for a living, and Mildred was initially far too proud to work in the serving class, the only jobs open to her.

It’s understandable that none of this made it into the film — the husband could hardly be cast a villain in the post-war climate, and movie star Joan Crawford would never play such an unsympathetic character — but how did Veda develop such a classist ideology? The Mildred of the film is grateful for her job as a waitress, while Veda is mortified that her mother is so low class as to wear a uniform. As the film continues, it becomes clear that Mildred is right when she says money is all that Veda lives for. Still, there is nothing in the film to explain the origins of her attitude; omitting the complicating factors from the novel mean Veda’s greed and coldness are mostly unexplained. The implication, primarily through studio advertising rather than the text of the film, was that Mildred was responsible. “Please don’t tell anyone what Mildred Pierce did!” said one poster, while ads referred to “trouble” that Mildred “made herself.”

There is also the heavy implication that Bert — philandering, lazy, useless Bert — was right when he said Mildred spoiled Veda. All Bert knew when he uttered those lines was that Mildred paid for dancing and piano lessons and bought the girl a dress she didn’t really need. We’re meant to think Bert was prescient and knew that Veda was in danger of becoming so desperately needy that she might do something terrible, and when the inevitable happened, it was because Mildred spared the rod and spoiled the child.

But as Proverbs 13:24 says, “He that spareth his rod hateth his son, but he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes.” Mildred’s devotion to her daughter is extreme enough that hate could easily be one component of it, and her final act of “spoiling” — paying rich playboy Monte (Zachary Scott) to marry her so she can give Veda a fancy home — is filled with a bubbling hostility underneath. But if Mildred hates Veda, she never expresses this outright; it’s her gal pal Ida (Eve Arden) who vocalizes just how supremely irritating the young teen can be, and always humorously. “Veda’s convinced me that alligators have the right idea,” Ida famously tells Mildred. “They eat their young.”

In order to create a melodramatic character that was the perfect Joan Crawford star vehicle, the film had to prevent Mildred from becoming too angry, too irrational, or too obsessed; instead, they made her both sympathetic and level-headed. The film then, perhaps accidentally, suggests that Veda’s snobbishness has less to do with parental nurturing than with cultural nurturing. In the absence of any family members to blame, her attitudes must have come from society at large, perhaps from the heavily commercialized media of the day. As Jacqueline Foertsch points out in American Culture in the 1940s, popular culture was the most commercialized it had ever been. Appearance and affluence were becoming increasingly important, and Veda’s intense materialism reflects this. Mildred Pierce seems to be saying that, sure, Mildred made mistakes, but society made more.

It’s that sort of world-weary cynicism that helps place Mildred Pierce firmly in the film noir cycle. Based on the novel by James M. Cain, Mildred Pierce shares many of the traits of a typical Cain noir, but with one notable difference: the female lead is not the femme fatale. Mildred uses men, they don’t use her, and she’s always the one with power. She’s the breadwinner and head of household when married to Bert, she exerts more control over business partner Wally Fay (Jack Carson) than surely any other woman has in his life, mother included, and when she doesn’t win the love of the land-poor Monte, she buys him like he was a tool in a hardware store.

Just like any good noir antihero, Mildred has a sidekick and considers her career the most important thing in her life. And just like any good noir villain, she likes to spoil her girl; it’s just that, with Mildred, that girl is her own daughter. As her desperation to make Veda happy increases, she eventually buys Monte, but it’s only after years of practice buying Veda’s affections, an uncomfortable parallel to some money man in a noir buying a pretty girl, setting her up in a nice apartment and asking her to call him “uncle.”

In Cain’s novel, Mildred’s inappropriate attentions toward Veda are explicitly laid out, but a film in 1945 could never suggest such a thing. It does quite a good job of hinting at it, though, by creating a Veda who is no sexy girl in the typical Hollywood fashion, but who alternates between masculine and sexless. Blyth plays this perfectly, especially in her later scenes: she’s gorgeous but stone cold, looking more like a beautiful statue than a human. She’s ambitious, ruthless, critical, and expects to receive what she feels is her due, both socially and financially, but without the usual tit-for-tat sexual exchange required of other female characters of the era. Some of the difference is due to her age, certainly, but it’s notable that even after she becomes a legal adult singing racy songs to soldiers in a riverfront dive, her affect is curiously neutral.

In a literary sense, the Freudian idea of boys and men separating from, or even outright rejecting, their mothers leads to masculinity; therefore Veda, by rejecting her mother, takes on masculine traits. When she latches on to Monte, just as she had with the rich young boy she falsely accused of having made her pregnant, she seems to have almost no intent beyond the acquisition of money. This culminates in a finale in which, in solid film noir tradition, she symbolically becomes the man when she guns down Monte, at the same beach house he first bedded Mildred in.

At times, it’s almost as though Mildred was simply unlucky enough to have a psychopath for a daughter, but as E. Ann Kaplan notes in Women in Film Noir, luck would have nothing to do with it: the Freudian model would place the blame squarely on Mildred, her maternal sacrifice being the root cause of unhealthy psychological issues. Elements of Mildred Pierce play on the maternal sacrifice narratives that made films like Stella Dallas (1937) and The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931) so powerful, and updates them for a more cynical era, positing that her sacrifice has not saved her children but ruined them, killing her youngest daughter and turning the eldest into a murderer.

This played toward men’s post-war fear of women refusing to return back to the home, too. Media took to radio and the big screen to remind women that their only jobs should be as wife and mother. Magazine articles, news stories and films were produced that were little more than thinly disguised instruction manuals on how women should raise their children. Mildred Pierce is frequently cited as one of the first of many examples of what was essentially peacetime propaganda.

There is a curious visual signifier that undermines that theory, however. Leading with Monte’s murder and told in flashback, Mildred Pierce features a beautiful, glamorous, well-lit past, almost entirely filled with clear and sunny days. It’s the present that becomes dark and cold, even a little surreal when Mildred is at the police station, the chief detective both gentle and cruel to her, telling lies in the same sentences as the truth. He means to humiliate and confuse her, punish her, make sure she knows it’s not the past anymore. He sends her away, the morning sun managing only a light gray haze, casting shadows on the cleaning women straining their backs to scrub the station floor by hand.

By the finale, men in authority, from Bert to the police, have arrived to clean things up by breaking the mother-daughter bond. At the same time, visually, it’s as though the film is looking back wistfully to the days when a working woman was not only accepted but patriotic, a time when women had a voice in their relationships, when it wasn’t a sin to sacrifice for their children because it was their primary mode of sociocultural power. The kind of strength and verve the U.S. hoped to recruit into the war effort just a year prior was now dangerous, which was why, for the good of society, the independent and successful Mildred had to be stripped of everything, even her children, by the end of the film. As she leaves the police station, it’s a bleak future ahead, those final stylized images she walks through almost Kafkaesque. And to make sure the message was fully received, Warner Bros. launched an ad campaign directed at returning U.S. soldiers, declaring the film the “big date” movie of the day. “Oh boy!” the poster shouted. “Home and Mildred Pierce!”

A freelance film critic and writer for the better part of a decade, Stacia Kissick Jones also plays classical guitar, reads murder mysteries and works tirelessly to consume all the caffeine in the world. Her work has appeared at Next Projection, Press Play, ClassicFlix and more.