This guest post by Rhianna Shaheen appears as part of our theme week on Bad Mothers.

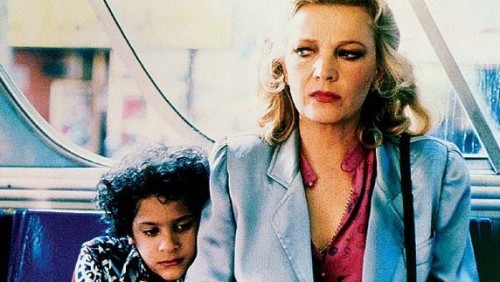

In John Cassavetes’ Gloria (1980), the title character must overcome a seemingly insurmountable obstacle: motherhood. Well, not exactly. When the mob wipes out a Bronx family, their neighbor Gloria (Gena Rowlands) suddenly becomes responsible for their 7-year old, Phil (John Adames). It’s more like forced guardianship, but the film constantly hints at her symbolic motherhood to the boy. Even when she’s pleading for Phil’s life, her gangster ex-boyfriend undermines her argument with the inevitable mother-son formula:

“I understand. You are a woman. He is a little boy. You fall in love. Every woman is a mother. You love him.”

Every woman is a mother? Yeah, no thanks. If Gloria is a “mother” to Phil then she’s also a lifetime member to the Bad Moms Club. In the beginning, Jeri, Phil’s real mom, calls on Gloria to take her kids. She tells Gloria that their family is “marked” by the mob. A gangster even waits in the lobby. Jeri begs her to protect her kids to which Gloria bluntly responds: “I hate kids, especially yours.” Despite her tough-talk, this ex-gun moll, ex-showgirl reluctantly agrees.

In her apartment, before the impending hit on his family, Gloria has difficulty relating to Phil. He’s aware that his family is in trouble, but she neither comforts nor coddles this soon-to-be orphan: “You want to play 20 questions? How about watching the TV for a while?” She doesn’t know how to talk to kids.

After a loud explosion, signifying the murder of his family, Phil is in shock: “I want my father! Papi! I hate you, you stupid person!” Gloria, shaken, now understands the gravity of the situation but still lacks the sensitivity to support him:

“I don’t know what to do with you, kid. My poor cat. What do I do with you? You know, you’re not my family or anything. You’re just the neighbor’s kid right?”

It’s both shocking and humorous. His entire family was just murdered, but she can only think of herself and her cat? To her defense, she didn’t sign up for this. She isn’t Daddy Warbucks. She’s a childless, single lady by choice.

Gloria loves her life. She loves her friends. She loves her cat. She saved all of her life so she could have some money. In one moment, she’s expected to just give all that away. She doesn’t want to die for this kid. Does that make her an unnatural woman? Or a rather flawed human being?

“Me, I’m not a mother. I’m one of those sensations. I was always a broad. Can’t stand the sight of milk.”

Not only does she lack so-called maternal instincts but also basic cooking skills. When she attempts to make eggs for Phil she inevitably becomes frustrated and burns them. This scene echoes a similar breakfast disaster in Kramer vs. Kramer (1979) in which newly single father Dustin Hoffman attempts to make breakfast for his son. However, Gloria is a woman, and thus belongs to generation and socioeconomic background that would demand woman to know how to cook. Thus she is even further stigmatized as a bad mother.

Gloria also shifts between wanting to abandon and wanting to protect the child when things gets tough. At one point she tells him to run home: “Run as fast as you can.” She walks a few steps with him, and then turns around, telling him to go. Although her attempt at abandonment is awful we understand her frustration. She cannot turn him into the police, because she’s been arrested. She also cannot turn on the mob, because they’re old friends of hers.

Regardless, Phil continues to follow her. He sees her as a substitute mother even if she’s a lousy one. Then when a group of gangsters confronts them on the street, Gloria must finally make a choice. It’s an opportunity to walk away, but instead she shoots the men, forever sealing her fate with Phil’s.

It’s a heroic act that speaks more to her humanity than to her ability to be a mother. While her feelings for him are at times ambivalent, Gloria ultimately commits herself to the boy’s survival. She empties her safety deposit box, changes hotels each night, and pistol-whips gangsters all for Phil. Together on the run, Gloria acts more like a partner-in-crime than a mother. Despite his efforts to be “the man” in this pairing Phil lets go of his hyper-masculine anxieties once he witnesses the toughness of this badass woman. She teaches him how to survive in this unfathomable New York environment.

Although there seems a desire to fulfill the mother-son mythos, the film does not explore their relationship in such clichéd terms as its 1999 remake. It lacks the sentimentality but has all the heart and truth to it.

As Cassavetes himself puts it:

“[…] these characters go on the basis that there are certain emotions and rules that go beyond words and assurances. They just know. […] Even when they’re thrown together, they don’t pretend to care about each other, it’s because of their personal trust and regard.” (from Cassavetes on Cassavetes)

“It was about a woman who beyond her control stood up for a kid whom she wanted nothing to do with […]”

However, in his discussion of the film, Cassavetes also evokes the same mythos and stereotypes that Gloria attempts to refute:

“I wanted to tell women that they don’t have to like children – but there’s still something deep in them that relates to children, and this separates them from men in a good way. This inner understanding of kids is something very deep in them that relates to children, and this separates them from men in a good way.”

Despite this backpedal into maternal instinct bullshit, I think Cassavetes has good intentions. In the end, Gloria is not defined by her ability to mother or understand this child (whatever that means) but by her heroism and humanity (not that those are mutually exclusive). Her desire to protect this helpless child is rather mistaken for motherhood.

Let’s consider Luc Besson’s Léon: The Professional (1994). A New York hitman shelters a 12-year old girl after her family is murdered by corrupt DEA agents. It’s almost an exact replica of Gloria except with the gender roles reversed and the cult film status. Instead of a father/daughter relationship, this unlikely pair acts as teacher/protégée. In fact, there is no mention of fatherhood at any time. Some pedophiliac undertones? Maybe. But no paternal transition.

Despite these double standards, Gloria represents an important cultural touchstone that is often overlooked. Released at the end of Second-Wave Feminism, the political relevance of this film is undeniable. It not only exposes the absurdities of gender norms but also captures the nuanced relationship women have with this idea of “motherhood.”

Rhianna Shaheen is a graduate of Bryn Mawr College with a BA in Fine Arts and Minor in Film Studies and Art History. Check her out on twitter!