This guest post by Rhianna Shaheen appears as part of our theme week on Demon and Spirit Possession.

(MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD!)

I have a Twin Peaks problem. I love Twin Peaks (1990-1991). In college, I was so obsessed with the show that I animated a Saul Bass-inspired titles sequence and wrote a spec script for my screenwriting class. However, as I became a better feminist, I awoke from my stupor of admiration for the show. I began to question the dead girl trope and ask myself, what is so funny about the sexual abuse and torture of an adolescent girl? I’ll admit I was thrilled about its announced return in 2016, but I wonder if a continued story will do more harm than good. Will the show continue to pull the demonic possession card when it comes to violence against women?

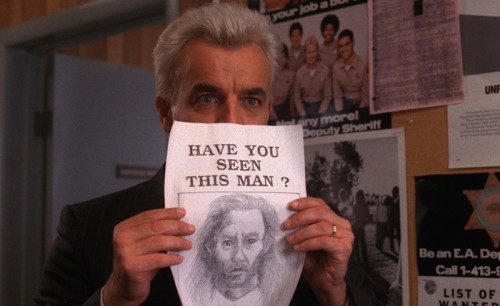

In the TV series, Special Agent Dale Cooper first encounters the evil spirit BOB in a dream. However, no one seems to see BOB in real life except for Sarah Palmer, who becomes increasingly unstable and otherworldly after her daughter’s murder. Much of this is due to her terrifying visions of BOB as well as her husband’s recent, strange antics. When Maddy Ferguson, Laura’s lookalike cousin, comes to support the Palmer family she sees similar visions of BOB in the house.

In the hunt for Laura Palmer’s killer, the local Sheriff’s Department is absolutely useless. As soon as Agent Cooper turns them on to Tibetan method and Dream Logic, all serious detective work goes out the door. It also doesn’t help that the town chooses to project this crisis outside of “decent” society. According to Sheriff Truman:

“There’s a sort of evil out there. Something very, very strange in these old woods. Call it what you want. A darkness, a presence. It takes many forms but…it’s been out there for as long as anyone can remember and we’ve always been here to fight it.”

But this old evil is within the town as well as outside of it. The show’s “quirky allure” tricks viewers into believing that Twin Peaks is different. That some places remain untouched by patriarchal evil. When we discover that it was Leland Palmer we are shocked. Leland’s mirrored reflection of BOB exposes the threat as one within the confines of the domestic space. It is patriarchy passing itself off as the loving and benign father of the nuclear family.

But what is even more shocking is that an entire community allows this to happen. In the prequel film, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992) we follow Laura Palmer through the final seven days of her life. Unlike the series, Laura has a voice here. We get to see her walking, talking, and acting like a teenager. When pages from her secret diary go missing she confides in her friend Harold that “[BOB] has been having [her] since [she] was 12” and “wants to be [her], or he’ll kill [her].” Harold does not believe her. It’s an extremely painful scene, because not only do we know she will die, but we know that many real-life victims of childhood abuse are often not believed either.

Days before her death, Laura finally discovers that it is her father. At dinner, Leland torments his daughter’s dirty hands and questions her about her “lovers.” Leland then pinches his daughter’s cheek. The sheer look of horror on Laura’s face is heartbreaking as she looks into the eyes of her abuser. Her mother, Sarah All-I-Can-Do-Is-Scream Palmer, tells her husband to stop, saying, “She doesn’t like that.” He replies, “How do you know what she likes?” It’s absolutely chilling, but even then the mother remains ignorant. How can everyone be so clueless?

As viewers, the warning signs seem obvious. The only way Laura can cope with this parasitic spirit is through copious amounts of cocaine and promiscuous sex with strange, older men. Why would a Homecoming queen who volunteered with Meals on Wheels, and tutored disabled Johnny, act this way? Well, to anyone schooled in recognizing sexual abuse the answer seems obvious. As many as two-thirds of all drug addicts reported that they experienced some sort of childhood abuse. The link between prostitution and incest or sexual abuse has also long been established.

Now this brings us to the question: Who’s at fault for Laura Palmer’s murder? Was it poor Leland or the demon that possessed him?

Moments before his death, Leland confesses his guilt to Agent Cooper:

“Oh God! Laura! I killed her. Oh my God, I killed my daughter. I didn’t know. Forgive me. Oh God. I was just a boy. I saw him in my dream. He said he wanted to play. He opened me and I invited him and he came inside me.”

With fire sprinkler water pouring over him, Leland seems cleansed of his sins. Lynch paints a pretty sympathetic portrait of Leland. He is cursed and tormented rather than murderous and abusive. He is blameless for his actions. Leland gets to go “into the light” while Laura is condemned to the purgatory of the Black Lodge.

In Diane Hume George’s essay Lynching Women: A Feminist Reading of Twin Peaks she perfectly discusses the problem with Leland’s poignant ending:

“We are instructed regarding how to situate our sympathies and experience our sense of justice. But this is just another clever use of the simplistic formula by which lascivious misogyny is presented in loving detail, […] scapegoating offenders whose punishment casts off the guilt that belongs to an entire culture ethos. And that ethos, both pornographic and thanatopic, not only goes free. It gets validated.”

Things become even more fucked up after Leland’s funeral where people remember him as a victim. Agent Cooper gives Mrs. Palmer some words of comfort:

“Sarah. I think it might help to teII you what happened just before LeIand died. It’s hard to realize here [points to her head] and here [points to her heart] what has transpired. Your husband went so far as to drug you to keep his actions secret. But before he died, LeIand confronted the horror of what he had done to Laura and agonized over the pain he had caused you. LeIand died at peace.”

I’m sorry, but death does not absolve you. Horrible people die and somehow we’re supposed to forget the history of horrible things they have done? We all die. This does not erase our actions, even if you’re a white cis male.

For a minute, let’s forget that BOB is a thing (ESPECIALLY when you consider that most of the town has no knowledge of these spirits and how their worlds work). These people are celebrating the memory of Leland Palmer after (I assume) finding out that he murdered and raped his own daughter (along with Maddy Ferguson and Teresa Banks). Excuse me, is anyone else bothered by how much denial these people are in?

Like many fans, I turned a blind eye, preferring to seek refuge in the myth of Killer BOB and the Black Lodge rather than identify the clear signs of abuse in front of me. As Cooper says: “Harry, is it easier to believe a man would rape and murder his own daughter? Any more comforting?”

While I no longer indulge the BOB theory, I do read BOB as patriarchal oppression. Its truth is one that women (Laura, Maddy, Sarah) see and know too well. Cooper only solves the mystery when he FINALLY believes and listens to a woman. Laura Palmer must whisper in his ear, “My father killed me” for him to finally understand.

M.C. Blakeman writes:

“While he may ultimately let Leland off the hook by claiming he was “possessed” by the paranormal “Bob” the show’s resident evil force, the fact remains that the women of Twin Peaks and of the United States are in more danger from their fathers, husbands and lovers than from maniacal strangers.”

I do believe that Lynch and Frost meant to use BOB as “the evil that men do” and as a means to understand family violence and abuse, but they jump around the issue so much that it only reflects uncertainty. The show’s inability to hold evil men responsible for their actions is too reminiscent of our own society. As soon as we answer “Who Killed Laura Palmer?” the show does its best to rebury the ugly truth that we so struggled to uncover. After that it fully commits to understanding the mythos behind it. This is troubling to me. As one of the most influential shows on television, Twin Peaks created a narrative formula that will forever shape the way this country looks at rape and child abuse. It’s important that as viewers we constantly question this, even if it is disguised as harmless, intellectual programming.

Rhianna Shaheen is a recent graduate from Bryn Mawr College with a BA in Fine Arts and Minor in Film Studies and Art History. Check her out on twitter!