|

| Star Trek Into Darkness movie poster |

|

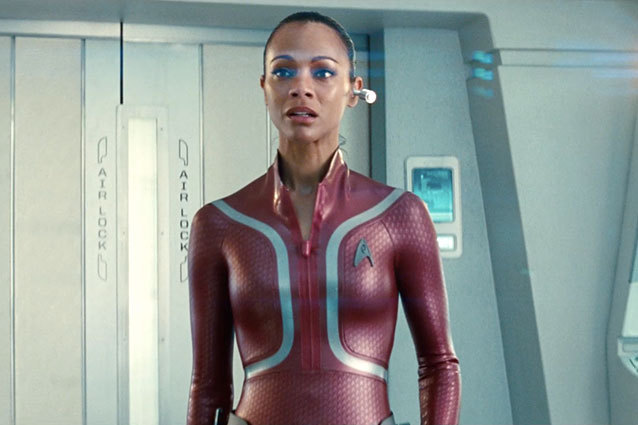

| Uhura strips in her quarters not realizing that Kirk is lecherously looking on. |

She is attracted to the intelligence of Spock, and the end of the film has the two falling in love. That, my friends, is the end of Uhura as an autonomous, interesting character. At the beginning of Star Trek Into Darkness, Uhura is dressing Spock for an away mission. How is that even remotely her job as a communications officer? She then proceeds to be childishly passive aggressive toward Spock because he’s displeased her and bickers with him during a dangerous away mission to Kronos, bringing her captain into the argument. Talk about unprofessional. Not only that, but her single valiant effort to placate a Klingon group that discovers them through the use of her knowledge of their language and culture fails miserably, nearly getting them all killed, thus proving diplomacy and non-violence are not valid tactical options for Starfleet.

Next, there’s Dr. Carol Marcus, played by Alice Eve, who is strong and spunky (stowing away aboard the Enterprise in order to investigate her father’s top secret weaponry), but, for some reason, it’s important to show her in her underwear as well.

|

| Guess it was crucial to the plot to learn that science officers do, in fact, wear undergarments to match their blue uniforms. |

Dr. Marcus is a female character who could’ve been so much more. She is given no history and her presence has little context other than to break up the sausage-fest with a bit of blonde eye candy. While she stands up to her father, who is the most powerful man in Starfleet, the original series character upon whom she is based is infinitely more compelling than this simple doctor of physics with a focus on weaponry. In fact, the original Dr. Marcus was a biologist who discovered how to create new worlds and new life. A weapons specialist is antithetical to that kind of focus on sustaining life and ecosystem balance, nevermind the powerful intellect and will that go into such a scientific endeavor. Though Abrams changes the timeline, it’s unrealistic to think that the doctor’s long path down the road of biology toward Project Genesis would’ve started after that timeline change. Due to the original character’s romantic history with Kirk replete with their son being born and Marcus choosing to pursue her work and raise the boy on her own, we know that Abrams is setting up Kirk and Marcus to fall in love in the third installment of his reboot. If we’ve learned anything from Uhura, we know that’s the kiss of death for any possibility of Marcus’ unfolding complexity and agency within the films.

I would’ve been happy, however, if Star Trek Into Darkness could have admitted to itself what its true genre is: Brokeback Mountain in space. This is actually a bromance about the love between Kirk and Spock that climaxes when Kirk sacrifices himself to save his ship. The two men are separated by glass as Kirk is irradiated in an inversion of the finale of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan when Spock dies. In both versions, the two men press their hands to the glass, but in Abrams’ reboot, Spock is overcome and weeping; the intensity of both men’s emotions is overwhelming as they say their impossible goodbyes.

|

| Spock and Kirk say their tearful, love-filled goodbyes. |

Spock then goes on an enraged rampage to destroy Khan and avenge Kirk’s death. Nothing about his demeanor throughout both films suggests that he would display this intensity of emotion in relation to Uhura. In fact, we have as an example his resigned acceptance of death earlier in the film, in which Spock is able to detach from his emotions towards Uhura and the impending reality of his own death. Not so with the death of Kirk.

Though the homoerotic subtext is strong in the finale of this film, JJ Abrams never really takes any risks with his reboot. The film hints at widespread corruption among Starfleet coupled with a clandestine militarization of the Federation, but Abrams chickens out from truly shaking up the Star Trek universe by having the corruption be limited to a single megalomaniac admiral. Abrams doesn’t depict women in power. How many women were around the table when the highest ranking members of Starfleet and their first officers assembled? I didn’t see any. Aboard the Enterprise, there are only the two women in this article (of dubious depth and agency) who have more than a single line of dialogue, and their outfits continue to model an outdated 70’s mode of sexism.

|

| Our beloved Enterprise goes down, unable to fly under the weight of so much mediocrity. |

Star Trek is the future for Christ’s sake. There’s no reason to continue to parrot the shortcomings of a series that always strove to show us a better, more egalitarian future but failed on many levels because it couldn’t see the ways in which it fell victim to the limiting ideology of its own era. This reboot may even have regressed from the days of Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, and Voyager, all shows that took the tenets of the original series and progressively attempted to push the boundaries on subjects of race, gender, sexuality, capitalism, imperialism, etc. In fact, Star Trek Into Darkness reveals that, as a culture, we are still falling victim to that same limiting ideology. Star Trek Into Darkness even has trouble imagining a future that is free from racial hierarchy and the gender binary. This film struggles and fails to see a world that has advanced beyond our limitations as a people and as a culture. Frankly, that is the poorest kind of science fiction because we look to sci-fi to either expose our contemporary hamartia or to teach us how to dream of a better, freer existence that is full of possibility and progress.