Written by Erin Tatum.

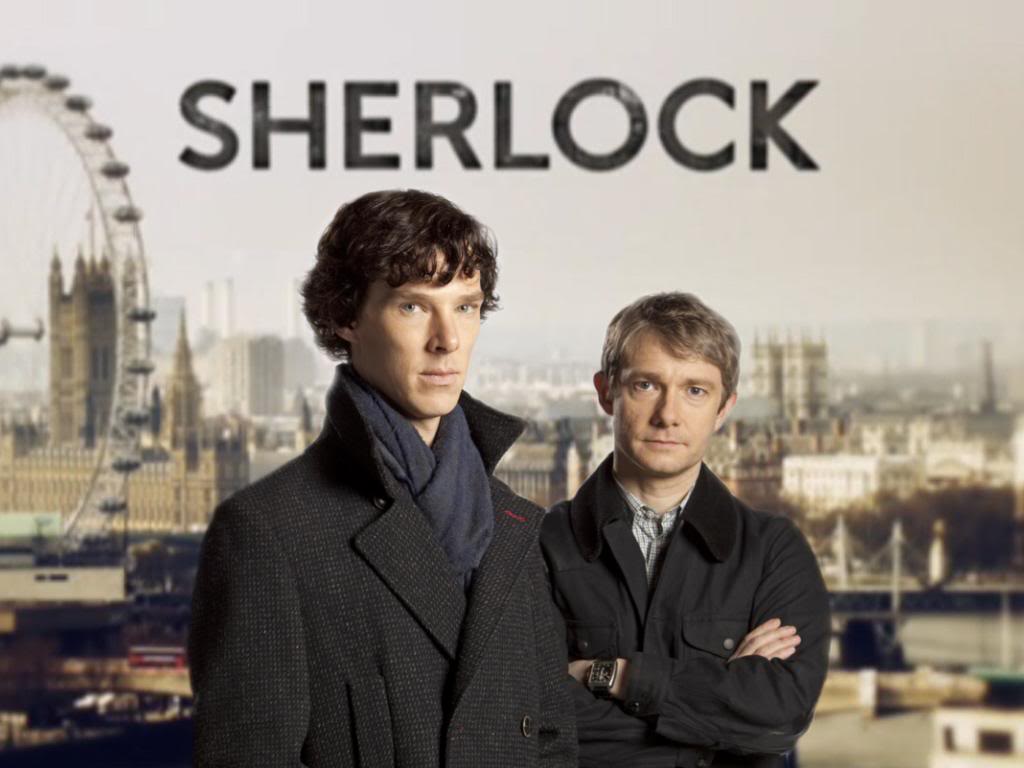

Sherlock is a fantastic show. As you can probably guess, it’s inspired by the works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, but imagined in modern-day London. Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock is arrogantly cerebral and painfully introverted, finding a perfect foil in the loyal and more rational ex-military doctor John Watson (Martin Freeman). Together, they form your classic unlikely pair that brings out all the best in each other, intensified by the adrenaline rush of high-stakes crime solving. The jokes are witty, the pacing is breakneck, and the emotion is genuine.

One of the main appeals of the show is the allegedly overt homoeroticism between Sherlock and John. It’s been television standard for a while now to feature bromances that play to the audience with tongue-in-cheek gay subtext. However, showrunners Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat delight in turning every episode into a perpetual game of gay chicken. The driving force behind the development of Sherlock and John’s relationship seems to be “let’s see how gay make them before we’re obligated to establish legitimate sexual tension.” They live together, work together, and regularly admit to their love and infatuation with each other. Almost every other character will either tease John about his implied crush or outright assume that they are a couple.

That feels pretty progressive, right? There’s been a recent onslaught of praise for bromances as essentially the only vehicle for mainstream acceptance of queer subtext, as if male emotional expression in itself is queer. If the “Johnlock” dynamic were allowed to persist on its own, I might be willing to begrudgingly stomach yet another instance of subtextual breadcrumbs being hailed as a watershed moment for queer inclusion. The problem is that any potential for alternative readings of their relationship is deliberately and painstakingly squelched by John’s constant and resentful vocalization of his heterosexuality.

Sherlock’s sexuality appears to be a source of fascination for John from the get-go. He professes to being open-minded, curiously interpreting Sherlock’s lack of social awareness to a carefully constructed veil over his personal life and somehow extrapolating that back out to internalized homophobia. John insists that he’s perfectly fine with Sherlock having either a girlfriend or boyfriend. All self-loathing queers need to snap out of their funk is lukewarm tolerance from straight people! Undeterred by Sherlock’s indifferent denial of a relationship with anyone, John conducts similar interrogations of Sherlock’s other friends, but fails to draw any concrete conclusions on Sherlock’s romantic history or orientation.

For someone who considers themselves to be so liberal towards others, John certainly has a lot of anxiety about his own sexuality. He reacts to every playful insinuation or misguided perception of his relationship with Sherlock with weary and sometimes angry defiance. When (spoiler alert) John informs their elderly roommate Mrs. Hudson that he’s met someone, she excitedly asks if it’s a man or woman, acting surprised when he informs her that he’s engaged to a woman. Growing impatient with her goodnatured skepticism, John irritably shouts, “I am not gay!” Insert laugh track here. This is why I can’t get behind any endorsement of bromance as the best mainstream queer tofu. Fuck the people who worship countless heterosexual male friendships as groundbreaking because they include a few zany domestic scenarios and the occasional double entendre. John’s sexuality is used and abused as the butt of the joke and he’s not even gay, which is somehow almost more insulting than if he were actually gay. The implication is that each reference to homoeroticism chips away at his manhood and slowly unravels his self-assurance, suggesting that no matter how progressive you claim to be in the abstract, to be queer is to be always anticipating humiliation. Moffat and Gatiss, we are well aware John is straight. Making him squirm for shits and giggles is unnecessary and juvenile. If you coyly stigmatize and degrade an identity to obsessively remind the audience everything that your characters are not, you wind up being just as exclusionary and discriminatory as shows that steer clear of queer subtext altogether.

Of course, any discussion of queer baiting draws focus from the other elephant (not?) in the room: Sherlock’s probable asexuality. Sherlock himself proclaims that he is a “high functioning sociopath,” but his difficulty grasping social cues as well as his astronomical intelligence also parallel the traits of Asperger’s. John in particular links this supposed diagnosis to his peculiar absence of romantic interest. When John investigates the matter with Sherlock’s friends, he isn’t trying to determine if Sherlock has a preference for men or women, he’s trying to suss out whether or not Sherlock has the capacity to feel at all. I should acknowledge that the narrative has never concretely established Sherlock actually having a mental disability. Nonetheless, the message that disability and asexuality are linked is unfortunate in a number of ways.

This aspect of the show creates an ideological war within me. On one hand, the tired and apparently benign stereotype that disabled people fundamentally lack any sort of sexual impulses makes me want to rip my face off and feed it to hyenas. On the other hand, asexuality is a completely legitimate orientation that should be respected and the fact that Sherlock may or may not have Asperger’s is entirely coincidental. Don’t think too hard about it though! The fact that that Sherlock doesn’t want to get laid only comes into play to underscore his characterization as a freaky weirdo with adorably oblivious, borderline misanthropic tendencies. Sherlock’s asexuality ironically leaves open a wider array of pansexual opportunities in the minds of many viewers. By the laws of television, the absence of something (especially sex-related) must be alluding to the presence of something. His romantic apathy is so uniform and universal that you can make an argument to pair him with just about anyone. It’s nearly impossible in modern society to fathom anyone being completely devoid of sexual desire. Consequently, a lot of viewers choose to simply attribute this potential lack to Sherlock’s extreme social awkwardness. He may want someone, but his chronic inability to feel empathy could obscure what’s going on behind the mask.

To be fair, Sherlock does not deny accusations of loneliness and has rare moments with women that could be interpreted as ambiguously romantic. I don’t care who Sherlock ends up with or if he ends up with anyone at all. The point is that I wish that it would be portrayed as acceptable for Sherlock to be asexual even if that’s not the case. He doesn’t want to pursue anyone, so why should we perceive his choice as repressive denial? This assumed cat and mouse mysteriousness conveniently also influences viewers to judge femininity and female characters on their ability to properly facilitate traditional masculinity within Sherlock, ergo sexual activity. Sherlock doesn’t need to wait around for whoever is judged as sufficiently Manic Pixie Dream Girl enough to awaken his libido. His friendship with John illustrates that Sherlock can still be a compelling character with emotions and compassion and meaningful relationships without having a love interest. He doesn’t need to have a partner to satisfy cliché character development and growth arcs. He is fine on his own, especially if he wants to be that way.

The writers have recently thrown the audience a few bones since we apparently can’t have a male lead without a few panty-dropping moments. (Spoiler alert) Much of the comedy during this series three premiere stems from the wild speculation as to how Sherlock faked his own suicide. One theory features Sherlock sharing a dramatic kiss with Molly, a lab assistant whose unrequited crush on Sherlock is regularly presented as pathetic and delusional. The other theory shows Sherlock sharing a giggle with his arch nemesis Jim Mortiary before suddenly leaning in for a kiss. It’s no accident that both accounts are initially established as actual events, revealed as fantasy sequences only when an outside character interjects and abruptly shatters the illusion.The person who proposes the homoerotic Sherlock/Mortiary hypothesis is a Gothic teenage girl addicted to social media, in a not-so-subtle lampoon of the yaoi fangirl stereotype. (A ballsy move in light of the predominantly female Johnlock fanbase.)

Needless to say, the episode was fantastic. I always enjoy when creators are able to poke fun at their own material. However, as far as the messages it sends, I’m reluctant to fully embrace it. I’m a sucker for shows that boldly go meta, but the undertones of those silly fantasies are hard to ignore. The fact that Sherlock kisses people in both sequences feels too deliberate. It’s as if Sherlock’s capacity for intimacy is meant to be the moment where the audience recognizes this chain of events as absurdly implausible. But why? If we’re all supposed to be secretly rooting for Sherlock to blossom into a Lothario, why does it feel so laughably ridiculous? Further, gleefully dangling wish fulfillment to tease the question of Sherlock’s orientation mocks the perceived inadequacy of and frustration with its absence. Fueling the widespread conviction that Sherlock has to be lusting after someone deep down contributes to continued asexual erasure.

There are many great things about Sherlock. It’s far and away one of the strongest television series in recent years. Ultimately, that doesn’t make the show immune to valid social critique. For a franchise that capitalizes on and even structures itself around queerness, Sherlock is pretty damn queerphobic. To laud subtext as representation is lazy, but more importantly, a show that regularly invokes queerness as mean-spirited comedy shouldn’t be considered a milestone because it perpetuates discrimination and pats itself on the back to boot. Giving a minority a thumbs-up while winking at the status quo is just two-faced demographic pandering. If there’s a case that Sherlock needs to solve, it’s why we continue to confuse vaguely defined tolerence with progressivism.