This guest post written by Danielle Miller appears as part of our theme week on Indigenous Women.

The horror genre has always been a realm that I naturally gravitated towards, simply because of the ways it embraces imagination, eccentricity, and feeds my curiosity for the unknown. The more involved I have become in social justice discourse and analysis, I have become cognizant of the lack of representations for Native people, and even more so when narrowed down to specific genres like horror. In the endless web of conundrums that Native peoples face, marginalization is a result of societal erasure, whether that be through stereotypes or the lack of representations all together.

Many times, I have been angered by the films that whitewash and stereotype, and they drove me to educate myself to dismantle those depictions in hopes of also addressing the further links to oppression. With so many resources available and outlets within social media to discuss my grievances, I have very much reached the saturation point of feeling the need to prove that Native oppression is real. Yes, I recognize the need for those conversations, but no longer do I question the validity in my analysis of linking the existence of power structures and settler colonialism to the struggles Indigenous peoples face.

Increasingly, I have begun to expand beyond basic concepts and feel more free in applying these ideals to everyday interest to assert that Natives are multidimensional in every aspect of our identities, personhood, and modern existence. Being burdened by the need to constantly educate, means exclusion from participating in the upper echelons of art forms such as film. That is not to say there haven’t been artists and creators asserting their vision, but as I see it, if we are denied basic understandings of personhood, then we are also being pushed out from artistic options as creators and from participating as an acknowledged and respected audience. Without being creators or consumers, Native people will also be denied opportunities for creating and overseeing accurate and positive representations.

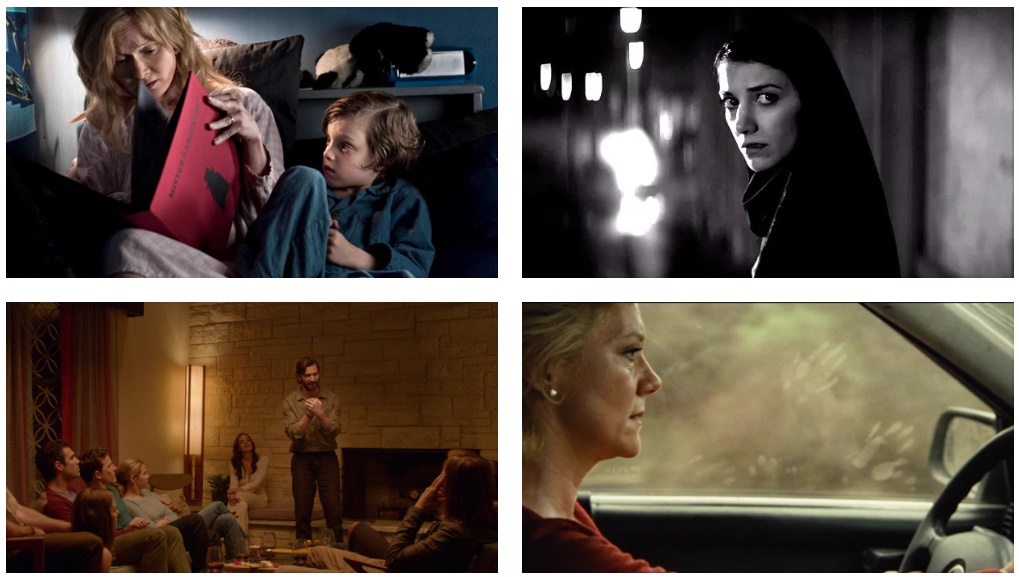

With that in consideration, I seek to influence popular consciousness by analysis of horror through a Native woman’s lens. One endeavor of asserting Native presence is through my analysis of the Native thriller film, Imprint (2007).

The story was written by Michael Linn and produced by prominent director of the “Ndn famous” film Smoke Signals (1998), Chris Eyre. With Smoke Signals being “the first wide-release feature film written, directed, co-produced, and acted by Native Americans” and popularly known as a positive representation of Native peoples, that gave me an optimistic feeling about Imprint. I had every intent to view this film in hopes that it wouldn’t just be a good watch, but also offer analysis of Native identity in proximity to broader themes of the horror genre.

One of the most important aspects of horror I seek to critique as a Native person, are the various tropes that so frequently repeat in film. One of the most pervasive tropes is “Indian mysticism.” Initially, I watched this film with hopes to see that trope turned on its head because the protagonist Shayla Stonefeather (Tonantzin Carmelo) worked as a lawyer. While it was successful in showing an authentic contemporary narrative, there were some moments that may still pander to that stereotype. During multiple scenes Shayla sees a wolf, (Hello “spirit animal” trope!) eventually this leads her to follow the wolf, where she meets a spiritual leader from her community. There weren’t terms used like “spirit animal” or “shaman” IN the film, but it was clear he had done spiritual work as he cleansed her house previously and gave her advice: “What you see might frighten you until you learn to listen.”

Where filmmakers were successful in not replicating the Noble Savage trope, was in the content of the Elder’s advice to Shayla. Rather than ending the conversation on a note of vague wisdom, the elder takes the conversation a step further in bringing up real issues:

“…I was here, these people were slaughtered, we forget, but it’s the trees, rocks that remind us. It is imprinted on this land. The past, present and future together, time doesn’t exist. Can you hear them? Can you hear their cries?”

The cries that he is referring to are an implied allusion to the genocide of Wounded Knee massacre. It is in this conversation that one realizes where the title is mentioned in the film, which then leads to further speculation on its meaning. In alluding to connection with the land, collective memory, and the concept of time, it ultimately sets the stage of paradigms as they relate to Indigenous survivance. I immediately saw a juxtaposition which challenges colonial perceptions of time and reiterates collective memory as a shared value of Native peoples. One can also assume this correlates to the identity conflicts Shayla faces, inner turmoil in questioning which paradigms are more valid: the cultural views she grew up with or the new views she internalized through her occupation as a lawyer? The supernatural element of that conversation, as well as the general idea of the film, is emblematic of a larger statement; one that diverts from the societal conception that Natives are ghosts of the past. In centering Shayla as the lead character experiencing supernatural phenomena and asserting her agency in confronting her many struggles, her character renders that popular misconception of the Native ghost, as paradoxical.

A significant aspect of this film was the fact it brought up real-life issues. In the special features of the DVD, an excerpt explains more about the making of the film. Initially, Imprint was supposed to be a story about a white family, which was decidedly changed after actor Misty Upham posed the question, “Why aren’t there more Indigenous representations in film?” This question is put into a deeper perspective with the knowledge of the suspicious and tragic details of her passing on October 4, 2014 — a tragedy emblematic of the issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous women worldwide, that is so reoccurring but goes unsolved. It’s interesting that the film started with her brother Nathaniel (Tokola Clifford)’s disappearance, as there is also little discourse on the disappearance of Indigenous men. In a way, this shifted things away from this turning into an expected story centered purely on the trope of a broken and battered woman. In mentioning the inspiration of Misty Upham, one can see the ways in which that influenced the dynamics of the story.

One barrier to the discussion of issues like Missing and Murdered Indigenous women, is white fragility. This film doesn’t shy away from displaying a white man as the cause for injustice. Shayla’s romantic relationship with a white man (Cory Brusseau) exacerbates her conflicts with culture clash and eventually endangers her life. But the way this played out was not over the top; a nice outcome in comparison to films that mention violence against Indigenous women, but end up reinforcing ideals by displaying scenes of gratuitous and triggering violence (such as rape scenes like in The Revenant). Although there were moments which underlined dynamics of whiteness and paternalism, there wasn’t fear to ultimately subvert that. The main character’s internalization of colonial systems as well as the paternalism of her white boyfriend running for office were a bit touchy in concern of identity (maybe too often simplified as universal Indigenous identity conflict) but they ultimately remained relevant to the outcome of the story.

Other references to larger issues of oppression, such as state sanctioned violence and the protest of the court decision, mirror the ongoing movements of resistance that Indigenous peoples have lived for centuries against the myriad faces of settler colonialism. It was unexpected to see a reference to Native protest in a horror film.

Other scenes challenged popular misconceptions of Native culture as stagnant, by showing cultural rituals and customs actively taking place. In one scene, Shayla smudges with her parents, in another they huddle together around a drum group. There was nothing performative in the manner of which either takes place, but is simply representative of Natives as contemporary peoples.

One symbol I do wish to address that plays into the trope of mysticism is the dream catcher, pervasive throughout the film. Numerous dream catchers inhabit Shayla’s brother’s room, to the point that it’s almost overkill. On the film’s poster and DVD cover, a dream catcher is placed next to wolf, which could admittedly be perceived as a bit stereotypical.

The dream catcher has been commodified to a point that it has the potential of pushing Pan Indianism. However, this brings up the question, would I remove them from the film? There are Native tribes all over that embrace the dream catcher symbol. While not always in the appropriate way of using them, there is an intercommunity connection in recognizing the dream catcher origin that is Ojibwe. It led me to think this is also representative of the complexities of Native cultural identity as an example of the intercommunity customs that organically take place, such as the process of cultural exchange. Recognizing those dynamics is what sets the distinction between when a symbol like the dream catcher is a cultural identifier or blatant cultural appropriation. While I wouldn’t conclude it must go, I am critical enough to recognize the need to make those distinctions and recognize the ways symbols are being represented in films. There could have been a better inclusion of the dream catcher that respects its purpose, but I also recognize that its relationship to Native people is different than with non-Natives.

After introducing the dynamic of the way Native symbols and identity are consumed, that leads me to the topic of intercommunity conversation and conflict. In one scene, the word “Apple” was spray painted across Shayla’s car as backlash to her complicity in a guilty verdict which ends up leading to a Native young man’s death. In another scene, Shayla argues with her mother (Carla-Rae Holland) about alleged mismanaging of funds from Tribal members and her mother points out how much she changed; Shayla retorts with the remark, “Our problems are self-inflicted.” On the surface, these are all complex issues that definitely should not be for the judgment of non-Natives, or even Natives outside of those communities. So I’ll admit, they made me feel a bit uncomfortable. While it is frustrating to know that non-Natives might watch this and feel affirmed in their presuppositions, it does give credence to the idea that Natives can be complex, flawed human beings and reclaim those struggles.

In summation, Imprint is a film that I enjoyed. There were emotional moments, a solid plot, a unique take on visuals of the spirits Shayla encountered (suspense with minimal effects), and a twist ending. I would recommend it just on the basis that the film cast so many Native actors. It was nice to watch something where I felt represented rather than alienated or excluded. It was refreshing to see new faces, rather than the standardized casting that caters to colonial/white supremacist beauty standards. Another huge positive for me was the use of Lakota language throughout the film, which further contributed to the idea of Native culture as thriving and contemporary. It also showed a sense of ethical dedication because of the process of cultural coaching and consultation that should be heeded when incorporating a cultural story in a film. There are aspects of the film that could have been fine-tuned and I’m sure the film would be even more engaging had the script been an Indigenous story from the beginning and Indigenous representation was a priority. Ultimately, films like this will be an example to open doors, and inspire more Indigenous filmmakers to pursue their talents and tell their own stories, regardless of societal perceptions and expectations.

See also at Bitch Flicks:

Complicating Indigenous Feminism: Shayla’s Story in Imprint

Danielle Miller is a Native American (Dakota/Lakota) with a Tribal Affiliation to Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, that grew up and currently lives in Southern Maryland. Danielle is an alumni of the University of North Dakota, a writer and co-founder of the horror platform called Never Dead Native. You can follow Dani on Twitter @xodanix3 and @NeverDeadNative.