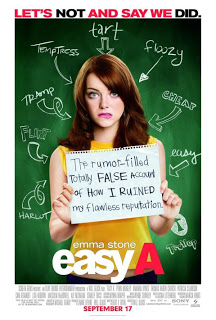

It appears that star power is on the rise for the funny, luminous

Emma Stone. She first caught my attention as the snarky cool girl who was way too good for Jonah Hill’s character in

Superbad

(and not because she was hot and he was fat, but because she was sarcastic and witty and he was whiny and entitled). She continued to charm me all the way through

Zombieland

, which was no easy feat when she was the prickliest of the four main characters. Finally, someone decided to give her a starring role in a movie called

Easy A. I saw the trailer for this and was immediately intrigued.

I thought, “Ooh, feminist issues! A comedic look at sexual hypocrisy in society, especially high schools! A cast with funny actors! Count me in!”

I saw it in the theater. I laughed. I sympathized with Emma Stone’s character Olive, found myself crushing on the character played by Penn Badgley even though he failed to even make a blip on my radar on the one episode of Gossip Girl I watched, and thoroughly enjoyed every scene with Stanley Tucci and Patricia Clarkson as Olive’s quirky, hippie parents. I went home with a smile on my face.

The smile soon turned into a straight line, which eventually became a scowl, as the more I thought about the movie, the more it annoyed me. I think it’s much less feminist than it seems, and for that matter, not as funny as I thought it was when I first saw it. (Warning: Spoilers ahead).

Why the Movie Fails on a Feminist Level

1) Olive is awesome. All other women are bitches.

How would I describe Emma Stone’s character, Olive Penderghast? First of all, she has the coolest name for a character in a teen movie since Anne Hathaway’s Mia Thermopolis in

The Princess Diaries .

. She’s also independent, feisty, compassionate, and refuses to let other people define who she is. When the school labels her as a slut, she decides to take her reputation into her own hands. Note that it’s already inherently problematic that she’s embracing the “slut” label as a form of rebellion – it’s kind of a stupid rebellion, in my opinion – but her motive

behind that rebellion is still laudable. And of course she Learns and Grows from the experience and finally tells the world that her sex life is nobody’s goddamn business but her own. That is a fairly satisfying conclusion, even if getting there was a bit of a struggle.

But let’s take a look at the other female characters.

We’ve got Rhiannon, the hypocritical best friend of Olive played by

Aly Michalka. At first, she eagerly devours Olive’s account of her made-up sex life, but then turns on her and joins the rest of the school in slut-shaming her. She’s a pretty crappy best friend, and of course, she’s motivated by jealousy.

We’ve got Marianne, played by

Amanda Bynes, the holier-than-thou religious girl who begins the campaign to slut-shame Olive. In addition to being judgmental, she’s also a cheap, less funny ripoff of Mandy Moore’s character from

Saved!

We’ve got all of Marianne’s friends, who join in on the slut-shaming campaign.

We’ve got Mrs. Griffith, played by Lisa Kudrow, who turns out to not only be an incompetent guidance counselor, but cheating on her husband with a student. Of course, her husband is the best teacher in the school, making her crimes even worse.

In other words, Olive is a great character because she’s not like the other girls – implying that most “other” girls are bitchy, catty, jealous, conniving, and mean.

I can’t praise a movie for its feminism if ONE female character is strong and the others are horrible.

2) The boys get a free pass for their douchey behavior.

We’ve talked about why the girls are bitches. But what about the boys? Are they portrayed as being jerks for taking advantage of Olive, for participating in a system that allows her to be shamed while they reap the benefits of her fallen reputation?

No. No, they are not. We’re supposed to think that the boys are wrong, certainly, but we’re also to feel sorry for them. Brandon asks Olive to fake-fuck him at a party so he can pretend to be straight and stop getting bullied. Never mind that he’s indirectly asking her to put her reputation on the line, so she can get bullied in a different way. We’re supposed to feel sympathy for the poor, bullied gay kid, not angry with him for being a hypocrite.

I also feel that we’re supposed to make the same kind of excuses for the other boys who ask Olive for permission to say they had sex with her. It’s wrong of them to do it, but they’re shy nerds who aren’t good with girls, so all they want is to build their reputations so that girls will like them. Wow, what a feminist message – guys use a girl’s fallen reputation to build up their own “street cred” so they can trick other girls into actually having sex with them! And the girl participates in this deceit of other girls! But that’s okay, because other girls are shallow! I think I have to take back what I said about Olive being awesome.

There’s also Cam Gigandet’s character, a 22-year-old high school student named Micah, who is dating Marianne. He is supposedly religious and chaste, but he turns out to be cheating on Marianne with Mrs. Griffith! And he tells everyone that he got syphilis from Olive! DUN DUN DUNNN! Is he condemned for this? No. Why? Because the poor guy was under pressure to lie after – wait for it – his mother beat him over the head and threatened to beat him more if he didn’t tell her who he slept with! His mother browbeats him, and his lover denies him. Older women = bitches, amirite, guys?

On a less serious note, there’s Thomas Haden Church’s character, Mr. Griffith. By Olive’s account, he is the best teacher in the school. Yet, when one of Marianne’s minions calls Olive a tramp in the middle of the class, and Olive responds by calling her a twat, he sends Olive to the principal’s office! This was all contrived so we could get a very awkward, unfunny scene in the principal’s office as he ranted about private schools vs. public schools (um…what?) but any teacher worth hir salt would have sent both Olive AND Nina to the principal’s office – or, at the very least, publicly condemned Nina for attacking Olive out of nowhere. Come on. That’s Classroom Management 101.

The only male character who the movie acknowledges to be a jerk is the guy who tries to pay Olive for actual sex. The screenplay and tone of the direction clearly condemn him. But he is the only one. The rest of the men (excluding Olive’s supportive, quirky dad) are either being used by evil bitches, or using women because they can’t help it.

3) Sex is still bad, especially for girls.

I appreciate that this teen movie is acknowledging slut-shaming and why it’s wrong. I really do. But I feel like it chickens out, by the very fact that Olive is still a virgin by the end of the movie. I think the movie is implying that slut-shaming Olive was bad because she never actually had sex. Would the screenwriters have written a movie with the same message about a sexually active young woman?

I doubt it, because of the scene where Olive confides in her mother. I didn’t mention Patricia Clarkson’s character under my first point because she’s not a bitch. She’s a quirky, supportive, loving mother. That’s great! But she admits to Olive that, when she was in high school, she had sex with a bunch of people (“mostly guys,” HAHA LESBIAN EXPERIMENTATION LOL!). But don’t worry, viewers! She didn’t have sex because sex is fun and enjoyable. She did it because she had low self-esteem.

Of course she did. That’s the only reason why teenage girls ever have sex, or why adult women ever have sex outside of monogamous relationships. Low self-esteem.

Pffft.

At the end of the movie, Olive spells out the message, that it’s nobody’s business what people do with their private lives. That’s admirable, and true. But the message means very little when the journey getting there is so icky and filled with double standards – the same double standards that the movie is supposedly criticizing, but tacitly embracing.

Why the Movie Fails on a Humorous Level: “Remember that funny line when…um…that person said that one thing?”

I have a great memory for dialogue. It’s a family trait that I share with my younger brothers. I can recite entire episodes of The Simpsons and Buffy the Vampire Slayer (and will do so upon request, though I’ve begun charging by the word. Speak to my agent and we’ll talk rates). I can recite movies after seeing them once. But the movie has to make an impression on me before I can do that. I have to really like the movie. The dialogue has to be memorable.

When I left Easy A, I tried to recall particular lines of dialogue that struck me as funny. I drew a blank. I had to go onto imdb.com to look it up. I never have to go to imdb.com to find funny dialogue. Reading through the “memorable quotes” page, there was only one line that really made me laugh. It was Mr. Griffith to Olive: “I don’t know what your generation’s fascination is with documenting your every thought… but I can assure you, they’re not all diamonds.”

That was very funny, and I like anything that mocks Facebook and Twitter (even though I use both).

But any other moments that made me laugh, I chalk up to the strength of the actors. The scene where Olive’s parents try to find out the “T” word that their daughter used in class would’ve been insufferable and awful in the hands of lesser actors than Stanley Tucci and Patricia Clarkson. The movie has a strong cast that can handle any dialogue you throw at them. I only wish they had better material to work with.

In Conclusion?

I didn’t talk about how the movie misses the point of The Scarlet Letter, because I hated The Scarlet Letter – I admire Hawthorne’s politics, but hate his prose, and when I was forced to read this book in my sophomore year in high school, I actually wrote in my annotations: “Does the scarlet A symbolize shame? Because I didn’t get it the FIRST HUNDRED TIMES YOU MENTIONED IT!” Misappropriating and misunderstanding literary themes seems like a very high school thing to do, so it oddly works for the film.

However, I’m afraid I can’t give Easy A the letter grade it wants. On a humorous level, it gets a C for “Cast is Awesome Despite Mediocre Dialogue.” On a feminist level, it gets an F for “Fauxminist,” with a note home to the parent: “Shows good effort, but fails to grasps key concepts.”

Lady T writes about feminism, comedy, media, and literature at the blog The Funny Feminist. Her essay “My Mom, the Reader” has also been featured at SMITH Magazine. A graduate of Hofstra University, she teaches English to eighth graders and writes fiction about vampires, superhero girlfriends, and feisty princesses.