This guest post by Nine Deuce also appears at her blog Rage Against the Man-Chine.

I know, I’m the last person in the industrialized world to see

Avatar, but I waited for several reasons. First, I was under the impression that it was based on a video game, rather than the basis for a video game, and if there’s one “artistic” genre I’m less into than films based on comic books, it’s films based on video games. Second, not only do I not go to the movies, but I rarely even watch movies. I don’t

go to the movies because I don’t like sitting up for that long, and because somehow I’ve ended up living in America’s hub for people who like to pretend they believe zombies really exist. We all know that people who are into zombies like to make spectacles of themselves in public — hence the existence of the thousand or so “Cons” that take place in this city every year — so going to the movies in my neighborhood often means enduring the presence of unwarrantedly smug drama club dorks who lack senses of humor, analytical skills, and the ability to determine when and where it might be appropriate to make histrionic displays of themselves via affectedly amplified snickering and banal “witty” commentary/audience participation (hint: at screenings of

Rocky Horror Picture Show only, which would not even transpire were everyone in America to suddenly sprout good — or at least non-embarrassing — taste). I don’t

watch movies because I generally disapprove of the direction the movie industry has been heading in since the late 80s (and, really, since the advent of the industry itself) and can only think of about ten movies that I enjoy watching for the reasons the people who made them intended. Even ten’s a stretch. Third, it’s a James Cameron movie. I pride myself on knowing nil about the movie industry and on my inability to name one set designer or screenwriter despite having spent five years living in LA, but even I know James Cameron is to blame for some of the more egregious examples of pointless cinematographic excess; in addition to having been tricked into seeing both

Bruno and

Joe Dirt in the theater, I also count

Titanic among the tortures I’ve endured under conditions of extreme air-conditioning and Gummi Bear-and-fake-butter-induced nausea. Finally, I like to strike while the iron is between

zero and forty degrees. I don’t want my movie reviews getting lost among all the timely ones, do I?

But alas, one night during an HBO free trial in December, Davetavius somehow convinced me that Avatar might be funny. It was, albeit in a very dispiriting sense. Probably most disheartening of Avatar’s many worrisome features was the loud and omnipresent dearth of vision, creativity, or even the ability to imagine anything more than a third of a derivative degree removed from current reality. That fundamental lack underlies both the hilarious tedium of each of the ideas presented and the deep concern the movie’s commercial and cultural success instilled in me, specifically because almost every word of the critical praise it garnered centered on just how original and inspired it was perceived to be by the blunderers we’ve entrusted to tell us what to think about the products of our culture industry.

For those of you lucky enough to have missed the movie, it takes place on a moon of some planet in the Alpha Centauri system called Pandora. It’s called Pandora because, like, when we go there, we, like, get into more than we bargained for. The unnecessarily complicated and terribly developed story is that Pandora is the reachable universe’s primo source for a mineral called (I swear to god) “unobtanium.” It’s called that because, like, it’s really hard to, like, obtain. We aren’t told what it is, exactly, that unobtanium does (or even is — the term is apparently used by scientists and engineers to refer to materials that are as of yet undiscovered that might make theoretical processes feasible should those materials ever be discovered, but in this movie it’s an actual substance that purportedly has an actual use and an actual monetary value), but we are ham-fistedly informed that it’s a BFD because the US has decided to set up a base on Pandora in order to mine it. The only problem is that the atmosphere on Pandora is poisonous to humans. Luckily, by 2154 , we’ve figured out how to make “avatars,” which are fabricated alien bodies linked to human minds via some voodoo mechanism whereby the human mind enters the alien body while the human is asleep and uses the alien body to putz around on the alien’s home turf until the alien gets sleepy, at which time the human wakes up and the alien goes back to bed. (Lord knows why we’ll be able to create living beings that we can operate like robots but won’t be able to come up with a better mechanism for controlling them; I guess it would have screwed up this ingenious story. And lord knows why they’re called avatars; I suppose because James Cameron rightly surmised that an audience of online gamer geeks would mistakenly think it very clever to name these beings after the graphic images they use to represent themselves in virtual worlds despite the fact that they are supposed to be real creatures living on real planets in other solar systems.)

Sigourney Weaver made the ill-advised decision to play Dr. Grace Augustine, the head of the avatar program, who hops into a pod herself every night in order to inhabit the world of the Na’vi, the blue creatures who live on Pandora (creatures that from this point on will be referred to as “blue fuckers”). One of her team dies right before he’s to be shipped out to Pandora. The avatars are expensive to create and are matched by DNA to the humans who they’ll be taking turns with to sleep, but (because shit just works out in the movies) he has a twin brother named Jake Sully, an ex-Marine who has been disabled in combat and displays the kind of machismo, naivete, stupidity, and simplistic morality we dumbasses here in the US seem to think add up to a complex, sympathetic male character. Sully takes his brother’s place, but Dr. Augustine doesn’t think much of him and only takes him out as a bodyguard. His avatar gets lost on an outing away from the base and the real stupid shit begins.

Sully finds himself lost in the forest when a female blue fucker named Neytiri shows up and saves him from some sparkly, terrifying beast. She’s no fan of the avatars who have been hanging around as she and the other blue fuckers see them as warlike dolts who have no understanding of how things work on Pandora, but she decides he’s worth saving when some Pandoran dandelion that floats around in the air and likes to hang around nice people decides it likes him. She takes him back to her parents, who happen tobe the blue fuckers’ high chief and priestess, and explains what occurred in the forest. They decide to let her school him in blue fucker bushido despite the fact that every other avatar they’ve ever met has been an asshole, and an extremely ridiculous montage of warrior training among CGI plants and animals ensues. The montage culminates in the viewer gaining an understanding of just how blue fucker society operates, which can best be summed up as, “whoever can rape a pegasus is one of us, but whoever can rape a pterodactyl can lead us!” (I’ll explain.)

After showing him how to hop around on leaves and sleep in the world’s craziest hammock, Neytiri explains to Sully that the blue fuckers can use their hair, which is basically a USB braid, to connect to their planet and control some of its creatures. She then introduces him to the Pa’li, the creatures that the blue fuckers ride around on to fly around and hunt, which look a lot like blue pegasuses. The way one forms a bond with one’s pegasus is to jump on its back and force one’s braid into a receptacle on the pegasus, after which point one can control the pegasus and use it as an aerial ridiculousness vehicle. Sully manages to rape a pegasus, an event that signifies his mastery of blue fucker bushido, and is then accepted by the blue fuckers as one of their own. That is, until the military-industrial complex fucks everything up.

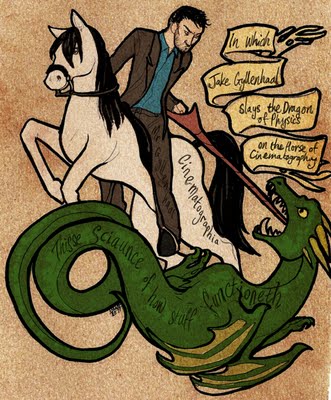

|

| If you rape the pegasus, you’ll be one of us, Jake! |

Sully, while a waking human back on base, is recruited as an informant on the world of the blue fuckers by Colonel Miles Quatrich, head of an organization called Blackwater. Wait, I mean Sec-Ops. Sec-Ops is a private security firm that works for RDA Corporation, and they ain’t got time for Dr. Augustine’s pussy-footin’ around and “learning” about these commie-ass blue fuckers. They want to head straight into the heart of Pandora and blast Hometree, where the blue fuckers live, right out of the ground in order to get at the giant unobtanium deposits that (naturally) lie beneath it. Quatrich, who looks like a real-life version of

Chip Hazard, tells Sully he’ll help him get the operation he needs to walk again if he’ll help him figure out how to best part the blue fuckers and their unobtanium. Sully adheres to the deal until he — SURPRISE — falls in love with Neytiri, the blue fuckers, their rugged communal way of life, and their USB connection to Mother Pandora.

A bunch of action-packed bullshit ensues wherein Sec-Ops attacks Hometree, Sully attempts to thwart them, they succeed anyway, and the blue fuckers find out Sully was on the wrong side to begin with and shun him. I thought that the movie might end once all that transpired, leaving us with some kind of inchoate message about militarism, environmentalism, and rich white people’s fanciful and stupid ideas about “traditional cultures,” but I was wrong. It got even more ridiculous and went on FOR ANOTHER HOUR.

Having been shunned by the woman and the blue fuckers he loves, Sully mopes around for a few minutes before — Eureka! — he figures out how to redeem himself. He seeks out the Toruk, a creature that has only been ridden five times in the history of all the blue fucker tribes, and manages to rape it. He then heads over to the Tree of Souls, where the blue fuckers connect their USB cables to Mother Pandora, to convince them that he’s OK after all, and that an endearingly dumb and reckless American ex-Marine is the right man to lead the blue fuckers to a resounding triumph over corporatism and militarism. They stop praying to the celestial DNS server for a few minutes, allow him back into the fold, and then resume chanting and praying to Mother Pandora to not allow a bunch of GI Joes kill them all. Mother Pandora intervenes and the film ends with Sully (who has somehow been made into a permanent blue fucker and no longer wakes up as a human when he goes to sleep) and a few other blue fuckers overseeing the Americans’ shame-faced retreat from Pandora back to their own planet, where they will presumably ruminate over the error of their ways among the ruins of their own long-since plundered ecosystem.

|

| Only the chosen one can rape the pterodactyl! |

I told you it was unnecessarily complicated and poorly developed. And blisteringly stupid.

Avatar is a science fiction movie. It admittedly differs from the specimens of the genre that those stranded aboard the

Satellite of Love might consider true sci-fi, but the general public puts it under that rubric. In fact, IGN called it the

22nd best sci-fi movie of all time. That’s a problem for the genre that purports to take us beyond the realm of what we can know and into the realm of what we can imagine.

As I watched Avatar, I for some reason (probably because predicting the next thing that would happen got boring once I realized I would never, ever be wrong) began thinking about the first time I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey and asked myself how the genre of science fiction and the movie industry as a pillar of American culture had changed in the time that had elapsed between the two films. What were the general cultural values and concerns being communicated in each of these films? What kinds of stories were being told about the world? How had cinema as a means of artistic communication and social commentary changed since 2001 was released? What do the methods of presentation in both films tell us about the ways in which our society has changed in the era of advanced mass communication? And, of course, how was gender represented?

I came to a few distressing conclusions. Naturally, I’ll get to the feminist criticism first. By the time Avatar came out, we’d traversed 41 years in which women’s status in society had purportedly been progressively improving since 2001 was released, but the change in representations of women in popular media, at least in epic sci-fi movies, doesn’t look all that positive. In 1968, we (or Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke) could imagine tourism in space. We could not, however, imagine women occupying any role in space exploration other than as flight attendants. In 2009 we (or James Cameron) could imagine female scientists and helicopter pilots participating in extraterrestrial imperialism, and we could even tolerate warrior-like blue female humanoid aliens as central figures in the plot of an movie, but we still couldn’t imagine a world in which traditional gender roles and current human beauty ideals aren’t upheld, even when that world is literally several light years and 155 years away from our own.

Provided that we accept the absurd and self-important idea that extraterrestrial creatures would resemble humans at all, why would they look like ten-foot-tall, blue fitness models posing for an elf-fetish magazine?

If that reference seems odd, compare Neytiri to this “night elf” (I rue the day I found out about

cosplay — thanks again, Japan):

Both the female and the male blue fuckers are tall, thin, ripped, and look like members of one of the bands in Strange Days, and they’re all wearing goddamned loincloths. There’s a reason Fleshlight makes an alien model that is purported to replicate a female blue fucker’s two-clitorised vulva, and that reason is that James Cameron couldn’t imagine a world in which aliens don’t look like people he’d want to fuck. Don’t believe me? Check out this excerpt from a Playboy interview he did about the movie (google it — I’m not linking to Playboy):

PLAYBOY: Sigourney Weaver’s character Ellen Ripley in your film Alien is a powerful sex icon, and you may have created another in Avatar with a barely dressed, blue-skinned, 10-foot-tall warrior who fiercely defends herself and the creatures of her planet. Even without state-of-the-art special effects, Zoe Saldana—who voices and models the character for CG morphing—is hot.

CAMERON: Let’s be clear. There is a classification above hot, which is “smoking hot.” She is smoking hot.

PLAYBOY: Did any of your teenage erotic icons inspire the character Saldana plays?

CAMERON: As a young kid, when I saw Raquel Welch in that skintight white latex suit in Fantastic Voyage—that’s all she wrote. Also, Vampirella was so hot I used to buy every comic I could get my hands on. The fact she didn’t exist didn’t bother me because we have these quintessential female images in our mind, and in the case of the male mind, they’re grossly distorted. When you see something that reflects your id, it works for you.

PLAYBOY: So Saldana’s character was specifically designed to appeal to guys’ ids?

CAMERON: And they won’t be able to control themselves. They will have actual lust for a character that consists of pixels of ones and zeros. You’re never going to meet her, and if you did, she’s 10 feet tall and would snap your spine. The point is, 99.9 percent of people aren’t going to meet any of the movie actresses they fall in love with, so it doesn’t matter if it’s Neytiri or Michelle Pfeiffer.

PLAYBOY: We seem to need fantasy icons like Lara Croft and Wonder Woman, despite knowing they mess with our heads.

CAMERON: Most of men’s problems with women probably have to do with realizing women are real and most of them don’t look or act like Vampirella. A big recalibration happens when we’re forced to deal with real women, and there’s a certain geek population that would much rather deal with fantasy women than real women. Let’s face it: Real women are complicated. You can try your whole life and not understand them.

PLAYBOY: How much did you get into calibrating your movie heroine’s hotness?

CAMERON: Right from the beginning I said, “She’s got to have tits,” even though that makes no sense because her race, the Na’vi, aren’t placental mammals. I designed her costumes based on a taparrabo, a loincloth thing worn by Mayan Indians. We go to another planet in this movie, so it would be stupid if she ran around in a Brazilian thong or a fur bikini like Raquel Welch in One Million Years B.C.

PLAYBOY: Are her breasts on view?

CAMERON: I came up with this free—floating, lion’s-mane—like array of feathers, and we strategically lit and angled shots to not draw attention to her breasts, but they’re right there. The animation uses a physics-based sim that takes into consideration gravity, air movement and the momentum of her hair, her top. We had a shot in which Neytiri falls into a specific position, and because she is lit by orange firelight, it lights up the nipples. That was good, except we’re going for a PG-13 rating, so we wound up having to fix it. We’ll have to put it on the special edition DVD; it will be a collector’s item. A Neytiri Playboy Centerfold would have been a good idea.

Sigh. I’ll take flight attendants in place of a sociopathic obsession with disembodied CGI female body parts that men invent in order to avoid confronting the fact that women are human beings. Fuck, I’ll take

stewardesses. Neytiri is permitted to talk, to take an active role in training Sully how to rape pegasuses, and to participate as a warrior in the fight against Chip Hazard and his robotic blue-fucker-ass-kicking devices, but she’s not allowed to not be a sex object. That shit is the

real final frontier, and something tells me we’ll be imagining visiting other

branes by jumping into bags of Doritos before we’ll imagine women being allowed to be human beings. She’s also not allowed to take an active role in choosing a mate, as we discover when she tells Sully that once one has raped a pegasus and become a real blue fucker warrior, the time has arrived for one to choose a mate. Even though she has

already raped a pegasus, is adept enough at it to instruct Sully on the subject, and happens to be the daughter of the blue fuckers’ HNIC, the prerogative to choose a mate is left to him as the man — even though he’s only an

honorary blue fucker — to choose her as a mate, at which point she must passively acquiesce. How romantical.

It probably isn’t fair to compare Avatar to 2001: A Space Odyssey, seeing as 2001 is one of the few movies I reluctantly label as “art” and Avatar tops Biodome on my list of the dumbest movies ever made, but it seems necessary. They’re both dubbed “epic science fiction” films, they are both purported to reflect the philosophical problems confronting the societies from which they emerged, they’re both considered to be among the greatest science fiction films ever made, and they’ve both inspired the production of thousands of paragraphs of analysis, criticism, and praise. They should be compared, if only on the basis of presentation and approach, in order to get a grip on the ways in which the medium has changed and the ways in which its message-delivery mechanisms have changed. Both of those changes have a lot to tell us about the trajectory our society has been on since the 60s.

Special effects technology has obviously made astronomical leaps since 1968, but that expansion of capabilities seems to have led to a crippling, rather than an enhancement, of the imagination. 2001 won an Oscar for effects. So did Avatar. Yet one second of 2001 holds more visual interest than more than two hours of film in Avatar. We now have the technology to create realistic images of absolutely anything we can dream up, but Pandora just looks like a sparkly jungle with a few gravity-defying mountains. The visual effects display such a drastic lack of creativity that it appears that Cameron paid more attention to making Neytiri “smoking hot” than to creating an alternative world, even when presented with unlimited possibilities for doing so.

Given that it was made in the late 60s, 2001 unsurprisingly explored humanity’s relationship with technology, the meaning of space exploration for human society, and several other philosophical problems that postwar America found itself faced with in the midst of the Cold War and the saturation of the culture with technology obsession. It did so by urging, expecting, and even requiring the viewer to think about the meaning of what they were seeing. 2001 was carefully executed on every level in order to create a visual and auditory experience that would inspire confusion and immediate identification with the idea that we were facing something big that needed to be grappled with. Visual effects, rather than serving as distractions or “eye candy,” operate as intellectual catalysts, and the laconic dialogue allows the audience to experience the film and consider the ideas being presented without the intrusion of a screenwriter who assumes they are too stupid to understand what is occurring. Nothing is spelled out, nothing is obvious, and nothing is trite, because Kubrick had enough confidence in his audience to entrust the interpretation of the meaning of the film to them. That’s a really big deal.

Avatar also (sort of) approaches some of the major issues facing contemporary aughts/teens society, including the immorality of late-stage capitalism, the disastrous reality and potential of militarism and environmental destruction, and humanity’s relationship with nature, but in Avatar, everything is spelled out, everything is obvious, everything is trite.

Cameron can only seem to conceive of an ideal society five light years and nearly two centuries removed from our own if it exactly mirrors an episode of Fantasy Island in which he’s the guest star, but it’s cool. He’s got a revolutionary political message to communicate: if we don’t all buy Priuses and reject militarism and imperialism right quick, we’ll destroy our planet and rudely intrude upon blue fucker utopias everywhere, thus ruining countless enlightened neo-primitive sex parties attended by the universe’s hottest aliens.

Despite the fact that he sets up the blue fuckers as a foil to all he believes is wrong with modern and future American society, Cameron is obviously a paternalistic racist, though he isn’t exactly unique in that respect. Privileged white urbanites hold some pretty hilarious ideas about “traditional cultures,” don’t they? Cameron clearly based the blue fuckers on his own nebulous and ill-informed ideas of various traditional cultures around the world, conceptions no doubt derived from the romanticized image Hollywood liberals seem to have of ways of life they’d like to convince everyone but themselves to embrace. Cameron repeatedly mentions Mayans in interviews about the movie and compares different facets of blue fucker society to Mayan society — which is no surprise since Mayans seem to be the new Cherokees among kombucha drinkers this week — but I wonder exactly how much he knows about what life might have been like for the typical Mayan. He probably doesn’t care any more than does the average LA dipshit who can be overheard extolling the virtues of some “traditional culture” that he has actually culled from his own narcissistic political and dietary allegiances and projected onto a society he knows nothing about. I’m sure that once the blue fuckers defeated the American war machine, they returned to their traditional ways, ways that include recycling, doing yoga, and having sex parties in their bedazzled jungle, where they drink their own handcrafted glitter palm wine and eat free-range pegasus-milk feta and (non-GMO) space maize tacos. (Maybe we’ll get to see that in the sequel.) Unfortunately, “traditional cultures” (and even their sci-fi/fantasy derivatives) tend to be fairly savage by current LA standards, what with all the pegasus rape and hunting and whatnot, but don’t worry. Traditional hunters and fantastical pegasus rapers thank the pegasuses and dead animals for allowing themselves to be oppressed, and they make sure not to let any dead animal parts go to waste, which they certainly did/do out of an au courant, Stuff White People Like sense of moral duty rather than basic necessity. (Just ask any foodie.)

Cameron’s conception of “traditional cultures” is nearly as nonsensical as his idea of what’s wrong with American culture and his suggestions for how we might reach a utopian neo-primitive future. Sec-Ops and RDA Corporation are obvious, although clumsy, stand-ins for the US military-industrial complex and its ties with big oil, and the blue fuckers and their USB network clearly represent “traditional cultures” and their purportedly closer relationship with the biosphere, but what is the point? I suppose it’s not terrible that Cameron is trying to sell an anti-militarist, anti-imperialist, pro-conservation message to people who are too dumb to have arrived at such ideas on their own, but I doubt it will be effective. In the first place, the blue fuckers only end up defeating Sec-Ops by praying to their goddess, Eywa, to intervene on their behalf. What is the take-home message? That we should pray to some hot goddess so that the military-industrial complex and rapacious corporations won’t succeed in destroying the Earth? That we should all get together and chant in order to bring about world peace and humanity’s harmony with nature? Is there even one person who wasn’t already convinced that imperialism, war-mongering, and environmental destruction are bad that has been swayed by twinkly special effects? I sincerely doubt that CGI can do a job that hundreds of far greater intellects than James Cameron’s have been working at for decades (if not centuries), and it’s fairly offensive that people are claiming he’s breaking any new ground. It’s also pretty snicker-worthy that Cameron is attempting a criticism of exploitative capitalism when he’s carved out a place for himself as the world’s most commercially successful film producer by exploiting and reflecting (and thus abetting) the stupidity of the public in order to enrich himself.

The effects are unadulterated eye candy and do nothing but distract the viewer from whatever hackneyed message Cameron is attempting to beat us over the head with, and the story line and dialogue are so stupid and insulting that I would have been offended if I could have stopped laughing. Even assuming that the issues Cameron pretends to be asking us to explore still hold some ambiguity and some intellectual ore that hasn’t already been mined (they don’t), Avatar won’t prompt anyone to ponder even these picked-over concepts because it’s just too stupid. Americans might have been dumbed down by five decades of television and commercial pop music to the point that we can’t think about large and potentially revolutionary ideas anymore anyway, but even if we have miraculously retained the ability, if the media asking us to do so are insults like Avatar, forget it. There is no room in a philosophical work of cinematic art for manipulative schmaltz, one-liners, video game graphics, tits, or ridiculous inter-species love stories. In the words of my friend Brian, “Avatar makes sure to include every single commercial emotion you could have,” and thus it manages to communicate nothing and inspire even less.

Nine Deuce blogs at Rage Against the Man-chine. From her bio: I basically go off, dude. People all over the internet call me rad. They call me fem, too, but I’m not all that fem. I mean, I’m female and I have long hair and shit, but that’s just because I’m into Black Sabbath. I don’t have any mini-skirts, high heels, thongs, or lipstick or anything, and I often worry people with my decidedly un-fem behavior. I’m basically a “man” trapped in a woman’s body. What I mean is that, like a person with a penis, I act like a human being and expect other people to treat me like one even though I have a vagina. She previously contributed a review of The Blind Side.