|

| X-Men First Class, 2011, Matthew Vaughn |

The X-Men franchise. I’ve been a fan of this ragtag team of mutants since the first movie was released (afterwards diving into the world of comics). The movies, along with their source material, have always been clear in their metaphorical status: These are not just mutants, these are everyone who is Different, Othered and Not Accepted by mainstream society. Previously, this analogy has certainly existed in the films, drawing specifically on Magneto’s history as a Jew in World War II, and on the idea of “coming out” as Bobby (Ice Man, played by Shawn Ashmore). Ian McKellen (Magneto) has

discussed the connection between X-Men, race, and sexuality in reference to the first three X-Men films.

Certainly as a metaphor (and hardly that) for gay society,

X-Men First Class succeeds. The movie is set up around the stories of Erik (Michael Fassbender) and Charles (James McAvoy), who we come to know later as Magneto and Professor X. Until they meet, about twenty minutes into the film, their stories are filled with loneliness and a sense of “am I the only one” — Charles’ despair is cut short by the arrival of Raven Darkholme/Mystique, whom I’ll discuss later at length. In the comics, Charles and Erik have a long history, a relationship of deep intimacy that spans decades. In

X-Men First Class, this relationship is condensed into mere months, and when discussing the film, my (male) friend explained that “For two men to get that close, that fast, there’s probably gay sex happening.”

The movie doesn’t dispute this. In fact, we are treated to a scene of Erik and Charles in bed together, laden with semi-sexual dialogue. Their conversations are deep, meaningful, their gazes fierce and full of longing. Were it not for the plot of the film, and attention paid=”center”> to other characters, I would be certain that the first half of X-Men F=”center”>irst Class was setting up for explicit gay sex. And, really, there’s=”center”> nothing wrong with this. If X-Men First Class is deemed the first gay s=”center”>uperhero movie, then I’m more than proud to have seen it during o=”center”>pening weekend, in a packed theater, and having heard no disparaging=”center”> remarks to that nature. Of course, there is also a huge problem with t=”center”>he “bromance” — Erik and Charles (and villain Sebastian Shaw, also) e=”center”>ssentially deny the validity of their human or female associates in=”center”> order to form a delightful world order on their own. It should be n=”center”>oted that Erik, Charles, and Sebastian all read as male, caucasian,=”center”> and capable of “passing” for human.=”center”>

The plot of this film, firmly rooted in the continuity of the=”center”> previously made X-Men films despite problems, deals primarily with the C=”center”>uban Missile Crisis, US government’s acceptance (and non-acceptance)=”center”> of mutants, and an almost James Bond-esque effect of lingering Nazi=”center”> sentiment. The villains: The Hellfire Club. Consisting of Sebastian=”center”> Shaw (Kevin Bacon), Emma Frost (January Jones), and two henchmen:=”center”> Riptide and Azazel, the Club fronts as a high-class strip club and=”center”> doubles as a lair to promote nuclear war. Shaw believes that mutants=”center”> are, literally, Children of the Atom, and seeks to promote a nuclear=”center”> holocaust (yes, he was involved with the last Holocaust in this canon)=”center”> that will wipe out humanity, leaving only a pure mutant race behind.=”center”>

Who we come to know as the X-Men (Charles, Erik, Beast, Mystique,=”center”> Havok and Banshee) align themselves with the CIA, the institution=”center”> first seeking information on the Hellfire Club and later working=”center”> directly against the nuclear threat. The primary voices of the CIA are=”center”> Agent Moira McTaggert (played by Rose Byrne, in a significant change=”center”> from the character’s comic origins) and a benefactor played by Oliver=”center”> Platt. These two are Good Humans and Allies, working with the mutants=”center”> to integrate and fight for their cause, which just so happens to also=”center”> be the mutants’ cause: the CIA obviously want to avoid nuclear war,=”center”> Erik wants revenge on his “creator”, and Charles wants to keep public=”center”> perception of mutants in a positive light, something that won’t happen=”center”> if Shaw succeeds.=”center”>

And overall, the movie doesn’t disappoint. Despite it’s failings=”center”> (again, I’ll discuss this later), X-Men First Class is a truly fun=”center”> movie. Director Matthew Vaughn (Kick-Ass) puts the film together with=”center”> a genuinely nice balance of humor, tense action, and political=”center”> intrigue. As much as I am baffled by some of the choices the film=”center”> chooses to make, and angered by several others, I can’t wait to see=”center”>X-Men First Class again. Count this off to my fangirling of the=”center”> series, perhaps, but the rottentomatoes.com=”center”> rating seems to agree. =”center”>

=”center”>

=”center”>

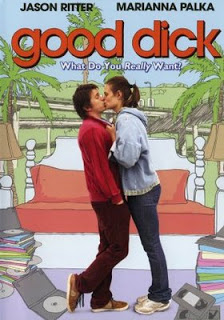

|

| Magneto is skilled at making funny faces while using his powers. |

The rest of this review deals with how

X-Men First Class handles race and gender, and contains detailed spoilers for the film.

As I stated, the X-Men franchise is no stranger to identifying with marginalized groups, and this film takes that one step further, while ironically completely failing to support any marginalized groups, aside from perhaps, LGBTs. I would hesitate to discuss a movie in these terms, had it not already made it abundantly clear that it was dealing, not only with a fictional universe, but as an analogy for ours.

There are several Characters of Color in X-Men First Class, but don’t go into the film expecting positive portrayals. When I refer to a Character of Color, I mean that said character’s “home” form is not traditional caucasian.

First, we have Darwin (played by Edi Gathegi): a young recruit to Charles’ team, his power is to “adapt to survive” (growing gills when submerged, turning rock solid to deflect physical blows). He receives limited characterization, much like the other recruits, and his first (and final) major scene involves attempting to deceive Shaw, “rescue” another mutant who has decided to deflect, and get quickly killed in the process. During Shaw’s monologue to the teens about why they should join his side, he states that by Charles’ way of thinking, they would rather “be enslaved or rise up to rule”. On “slaves,” the camera cuts to and lingers on Darwin, a black male. Could this be seen as a point of view shot from Shaw? Perhaps, but there are no others like it in the film. Save to say that this is one of the cheapest methods of marginalizing a character that I’ve seen in a recent film.

=”center”>

|

| The X-Men wonder where they can find a new token black character. |

There are characters of color among the background characters as well, throwaways like Angel, Riptide, and Azazel. These characters eitherhave no characterization (Riptide and Azazel) and work for the “bad guys” or, in Angel’s case, (to paraphrase) would rather have guys look at her in the strip club, than have guys look at her as a mutant. She defects to join the baddies as well.

Shaw’s, and eventually, Magento’s side certainly has validity. Not in the manner of wiping out an entire race to let the superior one flourish, but in the sense that mutants, and in this case, mutants who are already marginalized by their appearance, shouldn’t be forced to integrate into normal society, to forgo what makes them them. Mystique’s catch phrase, first bemoaning the fact that she is not, and later celebrating the idea of “Mutant and proud” echoes many movements in history, from Black Pride to Gay Pride. Mystique (Jennifer Lawrence) learns to wear her natural form and take pride in it.

Her journey to acceptance is central to the film. Growing up with Charles Xavier, Mystique learned to hate her natural blue form. She asks Charles, early in the film, if he would ever date her, looking like this [her blue form]. He gives her a line about being unable to think of her as anything other than his sister, but repeatedly reacts poorly to her use of blue form in public, unless, of course, it is to his ends. Raven ages slower than her adoptive “brother,” and as a result, Charles continually infantalizes her, keeps her drinking cola while he drinks at bars, informs her of her decisions and influences others. Her next love interest (and unfortunately intertwined in her seeking of acceptance) is Hank McCoy/Beast (Nicolas Hoult), who she sense an immediate bond with due to his deformed feet. Beast is geekily interested in the pretty girl, but doesn’t hide his motives. He wants her blood to create a formula that destroys the physical manifestations of their powers. Again, Mystique seeks his approval of her natural form, and Beast fumbles for an answer before settling on “You’re beautiful now,” gesturing to her clearly female, white caucasian, curvy body. She finally finds someone who appreciates her natural form in Magneto, however she gains it while reducing herself to a sexual object. Even while encouraging her to embrace her natural form, Erik compares Mystique to a tiger who needn’t be tamed.

The Mystique I know from canon (both movie and otherwise) doesn’t rely on others to decide whether or not she should be proud of her body. Granted, she has suffered for looking the way she does, but becomes stronger for it. In X-Men First Class, Mystique’s journey is so closely tied to male approval and attraction that it is hard to take her seriously, and certainly removes any feminist aspects to her character.

On the subject of Beast, there are always mutants who see their powers as more of an affliction than a blessing (Rogue in the original trilogy is the primary example). Beast views his gorilla-like feet as a hindrance to his otherwise immensely successful scientific and inventing career. Aside from tossing anything vaguely scientific on a self-proscribed disabled character, the film indulges in Beast’s point of view. He tries to cure himself of the physical affliction and is instead, in a thinly-veiled echo of Jekyll and Hyde, granted a full beastly form, complete with blue hair. Should Beast have embraced his disability instead of working against it? The film doesn’t deign to say. However, Magneto, with his band of physically different mutants, is quick to accept Beast’s new form. In most canon, where Beast continues to align at least loosely with Charles, he is relegated to background roles.

The film features a training montage (split-screens and everything!) that works to simultaneously progress the characters in their abilities, to give a bit of characterization, and to show case what a genuine asshole Charles Xavier is. His methods include accessing hidden memories to manipulate emotions, instructing young Banshee that the throat is “just a muscle” and can be trained (what does this say, then, to those who have muscles that cannot be trained?), and producing a seemingly endless supply of female mannequins for Havoc to annihilate while he learns to focus his explosive blasts. Along with his not-so subtle racism and casual outing of fellow mutants, Charles really is a winner.

Previous X-Men films have stayed clear of Charles’ dubious nature (aside from X-3, which I choose not to include in my canon by virtue of how bad it was) and, perhaps, for good reason. A leader with such obvious issues is difficult to get an audience to rally behind. While I appreciated that X-Men First Class did not shy away from the problematic nature of Charles Xavier, I wasn’t exactly keen on being made to watch him subtly marginalize his own people while building a team. Given that Charles ends the film in his iconic wheelchair, paralyzed, perhaps there is another layer to the discourse here, but I couldn’t find one.

In addition to proporting to align sensibilities with marginalized POC and failing, for a film that takes place in the 60s, I was expecting a Mad Men-esque deconstruction of gender relations, not an excuse to indulge in poor treatment of females. I was truly excited going in to this film, looking forward to how Emma Frost would do in her first prolonged big-screen portrayal. I was even excited when January Jones (Mad Men) was cast in the role: her layered portrayal of Betty is intense and powerful, two qualities any proper Emma Frost must have.

I was, to say the least, disappointed. Not only is the character written awkwardly, but Jones’ portrayal lacked any kind of depth. Emma Frost is used in the film as punch line, glorified butler, and sex object. With her powers — telepathy, shown to be strong enough to combat Xavier’s, and diamond form, protecting her physical form — there is no reason for Frost to do anything she doesn’t want to. She is essentially Sebastian Shaw’s busty lap dog, and getting nothing out of the arrangement. Where was the devious woman I’ve come to love?

My friend, Aimee LaPlant, who runs the fansite

EmmaFrostFiles.com, shares this dismay. She presented her view in

an interview with MSNBC sex columnist Bryan Alexander that Emma Frost was not “

created to be a slut,” as purported by Christy Marx, at least not in what the term slut has come to mean. Emma Frost is a powerful role model for girls: using her sexuality and enjoying it, building her powers,and effectively manipulating and controlling others to her ends.

The Emma Frost in X-Men First Class is none of these things. In fact, the portrayal of Emma in this film follows Christy Marx’s thesis almost exactly. This Emma is created to be a slut. She is sent to Russia to aide in negotiations to set up nuclear bases by Shaw, and instead of using her powers to gain information or influence, Emma “mind fucks” the Soviet official — an action that could be seen metaphorically, could be used as a cover for gaining information telepathically, however the film does not suggest that anything is happening aside from January Jones wearing sexy lingerie and a grown man groping a manifestation.

A woman presented as sexual and powerful is nothing to bemoan. However, when a woman, such as Emma Frost and Mystique, is reduced to only her sexual aspects this is troubling, and a far too easy route for filmmakers to take. What are Emma’s motivations? We don’t know. Mystique’s back story has been re-written to ensure that she relies on the approval of others rather than acceptance that is self-motivated.

As for the other main female character, Agent Moira McTaggert, I am not sure where to begin. Rose Byrne shone in the role, far beyond how the character was written. In comics canon, McTaggert is a brilliant scientist who comes to Charles’ aid with her research. In this film, she has been rewritten: she is American and not Scottish, she is a CIA agent — a lone woman in her office, she is the one coming to Xavier for his aid. Despite shining for a glorious five minutes near the finale of the film, McTaggert essentially works as the human POV for the film. She needs to learn about mutants, so through her, we do as well. Moira is one of the only females in the film who is comfortable using her sexuality (“using some equipment the CIA didn’t give me”) and manages to not be defined by it. In an eye-roll-inducing detail, her battle gear consists of a suitable uniform paired with platform shoes.

Two ending scenes in the film sum up her character, and the role of females in the film. During the climactic battle, Moira tries to catch Charles’ attention. He yells “Moira, be quiet!” — the men have a job to do. Finally, at a government debriefing, McTaggert tries to explain the events of the past days through her foggy memories (kindly induced by Xavier). “Gentlemen,” a lead agent says, his tone mocking, “this is why the CIA is no place for a woman.”

=”center”>=”center”>

=”center”>=”center”>

|

| The 60s is no place for mutants. |

Marcia Herring is a rollergirl receptionist from Southeast Missouri. She is still working on her graduate degree, but swears to have it done someday. She spends most of her time watching television and movies and wishes she could listen to music and read while doing so without going insane. She previously contributed a review of Degrassi: The Next Generation to Bitch Flicks.