Written by Lady T.

|

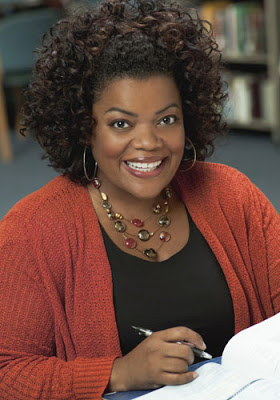

| Yvette Nicole Brown as Shirley Bennett on Community |

Anyone who has absorbed even a little bit of pop culture can see that the “sassy ethnic woman” archetype is ubiquitous in television and film. Women of color – particularly black and Latina women – are often used as sassy, finger-snapping side characters who exist only to provide amusing one-liners in the background of whatever white person drama or comic event happening in the forefront. (On a great scene from Scrubs, Carla and Laverne demonstrate how to act like a “minority sidekick from a bad movie”:)

One refreshing departure from the “sassy ethnic woman” stereotype is Shirley Bennett on Community. Played by Yvette Nicole Brown, Shirley is one of four people of color in the show’s main cast, though the only woman of color. In an interview with The Daily Beast, which included cast members Alison Brie and Gillian Jacobs and writer Megan Ganz, Brown discussed why Shirley is a refreshing character for her to play:

As a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight.

Shirley is, perhaps, the only main character on Community who has her own catchphrase, but the catchphrase – “That’s nice!” – is a far cry from the finger-snapping talking-through-the-nose stereotype demonstrated on the above clip from Scrubs. Shirley is exactly what Brown described: a woman filled with suppressed rage who covers up her anger by trying to be sweet and kind. But rather than being an example of a different kind of negative black stereotype – the Angry Black Person who bursts into a rage for no stated reason – the Community writers and Brown show that Shirley has plenty of reasons to be angry.

Like the other members of the Spanish study group, Shirley comes to Greendale Community College when she needs to start a new chapter in her life after the first chapter ended badly: her husband abandoned her and their two children, and she wants to earn a business degree so she can sell her baked goods. Christian and motherly, Shirley takes on a protective nature to the youngest members of the group (Annie, Troy, and Abed), tries to develop a camaraderie with Britta and act as a cheerleader for her flirty dynamic with Jeff, and does her best to ignore the sexual harassment from Pierce.

|

| Annie (Alison Brie), Britta (Gillian Jacobs), and Shirley get caught in a “reverse Porky’s” shenanigan |

Soon, Shirley develops close bonds with other members of the study group, trying to keep the group dynamic sweet, light, and happy – but time and time, her repressed anger rises to the surface.

Shirley flies into a rage when Jeff shows interest in a woman other than Britta, acting indignant on Britta’s behalf, but she later admits that she’s still in deep pain over her own divorce: “I was too proud to admit I was hurt, so I had to pretend you were,” she says to her friend.

Shirley is put out and offended when her friends don’t want to attend her Christmas party, taking their reluctance as an insult to her faith, but again, Britta gets to the heart of the matter: Shirley is desperate to recreate a tradition that’s important to her, that’s missing from her life since her painful divorce.

Shirley, when given a chance to act as campus security with Annie for a few days, insists on being the “bad cop” of the duo, a role that Annie also claims. The two characters clash during most of the episode because both are desperate for a change in image. While Annie wants people to stop seeing her as a sweet little girl, Shirley wants people to stop seeing her as a sweet motherly type. (More on that in a minute.)

|

| Annie and Shirley as campus security officers |

In short: Shirley has a lot of anger. What makes Shirley’s anger so refreshing is that her anger is not portrayed as a sign of her blackness, or her womanhood, but as the sign of a flawed, complex human being with legitimate pain. Sometimes her anger is towards a perceived slight that has nothing to do with her (assuming that her friends judge her for her Christianity when they don’t), and sometimes her anger is completely justified (getting fed up with Pierce’s harassment and racist comments). Sometimes she’s wrong, and sometimes she’s right – just like any other person.

Anger isn’t a character trait limited to Shirley, either. Annie also has repressed rage. The two women have a lot in common, “aww”-ing over cute things and getting upset when they’re not taken seriously. But of all the other characters in Community, Shirley seems to have the closest bond with Jeff. On the surface, they have little in common – he’s a white playboy sarcastic former lawyer, she’s a married black Christian woman with children – but just as Shirley covers her anger with a layer of sweetness, Jeff covers his with layers of blasé indifference. The fact that a young, insecure Shirley turns out to be Jeff’s former bully from when they were children seems perfect for their characters, and their friendship deepens – and some of their anger is assuaged – after they confront this issue.

|

| Jeff (Joel McHale) and Shirley, BFFs (sort of) |

Sometimes the writers on Community give Shirley short shrift compared to the other characters, as if they’re not sure what to do with a woman who is now re-married and in a happy relationship (their strengths are in writing damaged people, not content people). I’d also like the show to further explore her complicated dynamic with Britta, a woman with whom Shirley craves close friendship, but also finds threatening. Still, I’m grateful that Community allows Shirley to be as flawed, funny, and complicated as everyone else at Greendale Community College. She’s my younger brother’s favorite character, and I think that’s nice.

———-

As a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight. – See more at: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/02/28/community-alison-brie-yvette-nicole-brown-gillian-jacobs-megan-ganz-roundtable.html#sthash.cAOgrEkS.dpufAs a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight. – See more at: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/02/28/community-alison-brie-yvette-nicole-brown-gillian-jacobs-megan-ganz-roundtable.html#sthash.cAOgrEkS.dpufAs a black actor, it’s refreshing that I’m not playing the “sassy black woman.” It’s something that Dan Harmon was cognizant of from the beginning. It is something that I’m always cognizant of. Every woman on the planet has sass and smart-ass qualities in them, but it seems sometimes only black women are defined by it. Shirley is a fully formed woman that had a sassy moment. Her natural set point, if anything, is rage. That’s her natural set point, suppressed rage, which comes out as kindness and trying to keep everything tight. – See more at: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2012/02/28/community-alison-brie-yvette-nicole-brown-gillian-jacobs-megan-ganz-roundtable.html#sthash.cAOgrEkS.dpuf