This guest post by elle previously appeared at Shakesville.

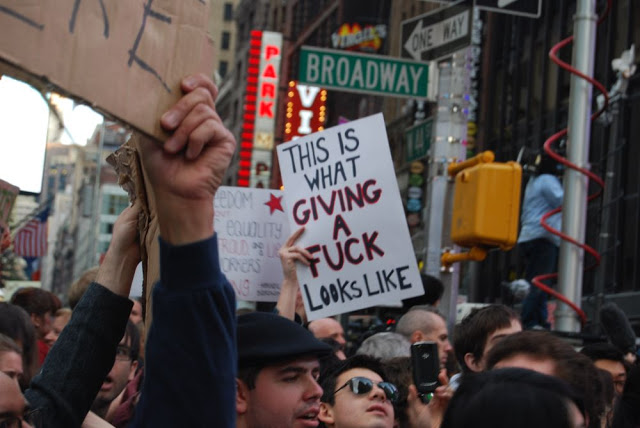

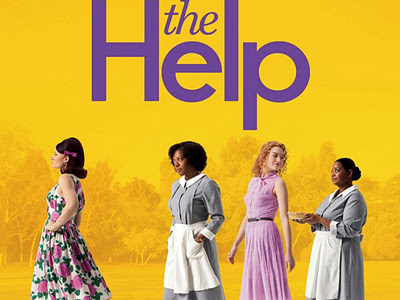

“The Help”—the film adaptation of the best-selling novel by Atlanta author Kathryn Stockett—is a feel-good movie for a cowardly [wrt to the ways we deal (or don’t deal) with issues of race] nation.

Despite its title, the film is not so much about the help—the black maids who kept many white Southern homes running before the civil rights movement gave them broader opportunities—as it is about the white women who employed and sometimes terrorized them.

And there you have it, the problem at the heart of works like The Help that blossoms into myriad other problems—the centering of white women in a story that is supposed to be about women of color, the positioning of white women as saviors who give WoC voice. As my colleagues in the ABWH note:

Despite efforts to market the book and the film as a progressive story of triumph over racial injustice, The Help distorts, ignores, and trivializes the experiences of black domestic workers.

I want to meld these critiques of The Help with my own critique of phenomena that make movies like this possible. My critique is rooted in who I am: My name is elle, and I am a granddaughter of The Help. And while I can never begin (and would never want) to imagine myself as the voice of black domestic workers, I can at least share some of their own words with you and tell you some places you can find more of their words and thoughts.

I. The Help’s representation of [black domestic workers] is a disappointing resurrection of Mammy… [p]ortrayed as asexual, loyal, and contented caretakers of whites… —ABWH

Early on in “The Help,” we hear the maids complain that they’ve spent decades raising little white girls who grow up to become racists, just like their mothers. But this doesn’t stop Aibileen from unambiguously loving the little white girl she’s paid to care for. —Boyd

When you put white women at the center of a story allegedly about black women, then the relationships between those two groups of women is filtered through the lens and desires of white women, many of whom want to believe themselves “good” to black people. That goodness will result in the unconditional love, trust and loyalty of the black people closest to them. They can remember the relationships fondly and get teary-eyed when they think of “the black woman who raised me and taught me everything.” They fancy themselves as their black nanny’s “other children” and privilege makes them demand the attention and affection such children would be showed.

I hated, hated, hated that my grandmother and her sister were domestics.

Not because I was ashamed, but because of the way white people treated them and us.

Like… coming to their funerals and sitting on the front row with the immediate family because they had notions of their own importance. “Nanny raised us!” one of my aunt’s “white children” exclaimed, then stood there regally as the family cooed and comforted her.

But, as the granddaughter of the help, I learned that the woman my grandmother’s employers and their children saw was not my “real” grandmother. Forced to follow the rules of racial etiquette, to grin and bear it, she had a whole other persona around white people. It could be dangerous, after all, to be one’s real self, so black women learned “what to say, how to say it, and sometimes, not to say anything, don’t show any emotion at all, because even just your expression could cause you a lot of trouble.”** They wore the mask that Paul Laurence Dunbar and so many other black authors have written about. It is at once protective and pleasant, reflective of the fact that black women knew “their white people” in ways white people could never be bothered to know them. These were not equal relationships in which love and respect were allowed to flourish.

Indeed, with regard to the white children for whom they cared, black women often felt levels of “ambiguity and complexity” with which our “cowardly nation” is uncomfortable. Yes, my grandmother had a type of love for the children for whom she cared, but I knew it was not the same love she had for us. I think August Boatwright in

the film adaptation of The Secret Life of Bees (another film about relationships between black and white women during the Civil Rights Era that centers a white girl) voiced this ambiguity and complexity much better. When her newest white charge, Lily, asks August if she loved Lily’s mother, for whom August had also cared, August is unable to give an immediate, glowing response. Instead, she explains how the situation was complicated and the fragility of a love that grows in such problematic circumstances.

Bernestine Singley, whose mother worked for a white family,

was a bit more blunt when the daughter of that family claimed that Singley’s mother loved her:

I’m thinking the maid might’ve been several steps removed from thoughts of love so busy was she slinging suds, pushing a mop, vacuuming the drapes, ironing and starching load after load of laundry. Plus, I know what Mama told us when she, my sister, and I reported on our day over dinner each night and not once did Mama’s love for the [white child for whom she cared] find its way into that conversation: She cleaned up behind, but she did not love those white children.

II. The caricature of Mammy allowed mainstream America to ignore the systemic racism that bound black women to back-breaking, low paying jobs where employers routinely exploited them. Furthermore, African American domestic workers often suffered sexual harassment as well as physical and verbal abuse in the homes of white employers. —ABWH

From films like

The Help, we can’t know what life for black domestic workers is/was really like because, despite claims to the contrary, it’s not black domestic workers talking! The ABWH letter gives some good sources at the end, and I routinely assign readings about situations like the

“Bronx Slave Market” in which black women had to sell their labor for pennies during the Depression. The nature of domestic labor is grueling, yet somehow that is always danced over in films like this.

As is the reality of dealing with poorly-paid work. In her autobiographical account, “I Am a Domestic,” Naomi Ward describes white employers’ efforts to pay the least money and extract the most work as “a matter of inconsiderateness, downright selfishness.” “We usually work twelve to fourteen hours a day, seven days a week,” she continues, “Our wages are pitifully small.” Sometimes, there were no wages, as another former domestic worker explains: “I cleaned house and cooked. That’s all I ever did around white folks, clean house and cook. They didn’t pay any money. No money, period. No money, period.”**

Additionally, the job came with few to no recognizable benefits. The federal government purposely left work like domestic labor out of the (pathetic) safety net of social security, a gift to southerners who wanted to keep domestic and agricultural workers under their thumbs. After a lifetime of share-cropping and nanny-ing, my grandmother, upon becoming unable to work, found that she was not eligible for any work-based benefit/pension program. Instead, she received benefits from the “old age” “welfare” program, disappearing her work and feeding the stereotype of black women as non-working and in search of a handout. (I want to make clear that I am a supporter of social services programs, believe women do valuable work that is un- or poorly-remunerated and ignored/devalued. So, my issue is not that she benefited from a “welfare” program but how participation in such programs has been used as a weapon against black women in a country that tends to value, above all else, men’s paid work.)

[Their white employers gave] my grandmother and aunt money, long after they’d retired, not because they didn’t pay taxes for domestic help or because they objected to the fact that our government excluded domestic work from social insurance or because they appreciated the sacrifices my grandmother and her sister made. No, that money was proof that, just as their slaveholding ancestors argued, they took care of their negroes even after retirement!

The various forms of verbal and emotional abuse suffered are also glossed over to emphasize how black and white women formed unshakeable bonds. By contrast, Naomi Ward described the conflicted nature of her relationships with white women and being treated as if she were “completely lacking in human dignity and respect.” In

Coming of Age in Mississippi, Anne Moody says of her contentious relationship with her employer, Mrs. Burke, “Mrs. Burke had made me feel like rotten garbage. Many times she had tried to instill fear within me and subdue me…”

Here, I wrote a bit about the participation, by white women, in the subjugation of women of color domestic workers.

And what of abuse by white men? “‘The Help’s’ focus on women leaves white men blameless for any of Mississippi’s ills,” writes Boyd:

White male bigots have been terrorizing black people in the South for generations. But the movie relegates Jackson’s white men to the background, never linking any of its affable husbands to such menacing and well-documented behavior. We never see a white male character donning a Klansman’s robe, for example, or making unwanted sexual advances (or worse) toward a black maid.

This is a serious exclusion according to the ABWH, “Portraying the most dangerous racists in 1960s Mississippi as a group of attractive, well dressed, society women, while ignoring the reign of terror perpetuated by the Ku Klux Klan and the White Citizens Council, limits racial injustice to individual acts of meanness.”

Why the silence? Well, aside from the fact that this is supposed to be a “feel good movie,” when you idolize black women as asexual mammies in a culture where rape and sexual harassment are often portrayed as compliments/acknowledgements of physical beauty (who would want to rape a fat, brown-skinned woman?!), then the constant threat of sexual abuse under which many of them labored and still labor vanishes. But black women themselves have long written about and protested this form of abuse. My own grandmother told me to be careful of white boys who would try to make me “sneak around” with them and an older southern man who was a fellow grad student told me that he and other southern men believed it was “good luck” to sleep with a black woman. Here, in the words of black women, are acknowledgements of how pervasive the problem was (is):

“I remember very well the first and last work place from which I was dismissed. I lost my place because I refused to let the madam’s husband kiss me… I believe nearly all white men take, and expect to take, undue liberties with their colored female servants.”*

“The color of her face alone is sufficient invitation to the southern white man… [f]ew colored girls reach the age of sixteen without receiving advances from them.”*

“I learned very early about abuse from white men. It was terrible at one time and there wasn’t anybody to tell.”**

These stories abound in works like Stephanie Shaw’s What a Woman Ought to Be and Do, Paula Giddings’s When and Where I Enter, Deborah Gray-White’s Too Heavy a Load, and other books where black women are truly at the center of the story. Black women’s concern over sexual abuse is serious and readily evident, but The Help, according to the ABWH, “makes light of black women’s fears and vulnerabilities turning them into moments of comic relief.”

III. The popularity of this most recent iteration [of the mammy] is troubling because it reveals a contemporary nostalgia for the days when a black woman could only hope to clean the White House rather than reside in it. —ABWH

This mention of the White House is not casual (Boyd opens her review with an Obama-era reference, as well). I’m currently working on a manuscript that examines portrayals of black women and issues of our “desirability,” success, and femininity in media. To sum it up, we, apparently, are not desirable or feminine and our success is a threat to the world at large. Many black women are trying to figure out why so much is vested in this re-birthed image of us (because it’s not new). One conclusion is that it is a counter to the image of Michelle Obama. By all appearances successful, self-confident, happily married and a devoted mother, she’s too much for our mammy/sapphire/jezebel-loving society to take. And so, the nostalgia the ABWH mentions comes into play. It’s a way to keep us “in our place.”

It happens every day on a smaller scale to black women. I remember someone congratulating me in high school on achieving a 4.0 and saying that maybe my parents would take it easy on me for one-six weeks chore-wise. The white girl standing with us, who always had a snide comment on my academic success, quickly turned the conversation into one about how she hated her chores and how she so hoped the black lady who worked for them, whom she absolutely adored, would clean her room.

Even now, one of my black female colleagues and I talk about how some of our students “miss mammy” and it shows in how they approach us, both plus-sized, brown-skinned black women with faces described as “kind.” I do not need to know about the black woman who was just like your grandmother, nor will I over-sympathize with this way-too-detailed life story you feel compelled to come to my office and (over)share.

IV. [T]he film is woefully silent on the rich and vibrant history of black Civil Rights activists in Mississippi. Granted, the assassination of Medgar Evers, the first Mississippi based field secretary of the NAACP, gets some attention. However, Evers’ assassination sends Jackson’s black community frantically scurrying into the streets in utter chaos and disorganized confusion—a far cry from the courage demonstrated by the black men and women who continued his fight. —ABWH

Embedded in this is perhaps the clearest evidence of the cowardliness of our nation. First, we cannot dwell too long on racism, in this case as exemplified in the Jim Crow Era and by its very clear effects. “Scenes like that would have been too heavy for the film’s persistently sunny message,” suggests Boyd. I’d go further to suggest that scenes like that are too heavy for our country’s persistently sunny message of equal opportunity and dreams undeferred.

Second, when we do have discussions on the Jim Crow Era, we have to centralize white people who want to be on what most now see as the “right” side of history. They weren’t just allies, they did stuff and saved us! And so, you get stories like

The Help premised on the notion that “the black maids would trust Skeeter with their stories, and that she would have the ability, despite her privileged upbringing, to give them voice.” Or like

The Long Walk Home, (another film about relationships between black and white women during the Civil Rights Era that centers… well, you get it) in which you walk away with the feeling that, yeah black people took risks during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, but the person who had the most to lose, who was bravest, was the white woman employer who initially intervened only because she wanted to keep her “help.”

These stories perpetuate racism because they imply that it is right and rightful that white people take the lead and speak for us. (On another note, how old is this storyline? Skeeter’s appropriation of black women’s stories and voices, coupled with the fact that “Skeeter, who is simply taking dictation, gets the credit, the byline and the paycheck” reminded me so much of

Imitation of Life, when Bea helps herself to Delilah’s pancake recipe, makes millions from it, keeps most for herself and Delilah is… grateful?!) The moral of these stories is, where would we have been without the guidance and fearlessness of white people?

I know this moral. That’s why I have no plans to see The Help.

_______________________

*From Gerda Lerner, Black Women in White America.

**From Anne Valk and Leslie Brown, Living with Jim Crow.

elle is an assistant professor who does a little of this an a little of that—primarily social history courses, some Women’s Studies and African American Studies classes, and seminars on the historical construction of race, gender, and class with a focus on how those constructions influence and are reinforced by popular media. She writes about the South and about black women’s paid and unpaid labor. She’s also a single mama to a teenaged boy that would test the patience of Mother Teresa, has an unhealthy love for TV shows with “forensic” and/or “crime” in the title, and is an amateur caterer.