Author: Stephanie Rogers

Profiling Gender: Punishing the Professional for the Personal on ‘Criminal Minds’

When we look closely at the numbers of women portrayed as professionals in these shows and the number of women actually working in these professions, it is clear that feminism is embedded in dramas like Criminal Minds. In 2009 Kimberly DeTardo-Bora published the results of a study in which she conducted a feminist content analysis of popular prime-time crime dramas from January 2007 through May 2007. The details of her study are fascinating, and I encourage you to read the rest of her article in the journal Women & Criminal Justice. In order to capture the wide variety of professions depicted in crime dramas, researchers looked at the “criminal justice” field, which included police, lawyers, judges, federal agents, etc. What the study found was that among the main characters in their sample of crime dramas, 54.9% were male, and 40.6% were female. In addition to the nearly equal numbers of men and women, women appeared to work in the same types of positions as men; they were just as likely to be prosecutors, or criminal investigators. While in prime-time dramas women appear to have achieved near equality with men in the criminal justice fields, as DeTardo-Bora points out, the reality is slightly different: “According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2006), 26% of criminal investigators and detectives [were] female. In [De-Tardo-Bardo’s] study, then, female criminal investigators were in fact overrepresented (39.3%).” Even though Criminal Minds was not in the sample of crime dramas for this study the gender breakdown of its cast reflects the overrepresentation of women. Of the seven main characters (six criminal investigators, and one technical analyst) 4 are male, and 3 female. This overrepresentation of women visually reinforces the idea that the goals of feminism, at least the numerical ones, have been achieved. Women characters, then, do not have to overtly espouse feminist principles, because in their television reality there is no need for them.

As a part of the cultural landscape, embedded feminism, suggests that overt sexism does not have to be confronted, and enlightened sexism can circulate freely. Douglas defines enlightened sexism as, “[the insistence] that women have made plenty of progress because of feminism – indeed, full equality has allegedly been achieved—so now it’s okay, even amusing, to resurrect sexist stereotypes of girls and women.” The number of women represented on a show like Criminal Minds supports the notion that equality has been achieved. The fact that women are also overwhelmingly the victims of crime on the show can go unremarked, as can the increasingly voyeuristic torture-porn like depictions of female cadavers. The embedded feminism of the Criminal Minds world also masks the enlightened sexism in the form of double binds the women investigators face.

Although there are several problematic patterns in the way the writers of Criminal Minds treat the female agents on the show, I want to focus on the women characters as they are written off the show. On June 14th 2010 CBS announced that it would not renew AJ Cook’s contract for the sixth season, which as Michael Aussielo put it in his “Breaking” report for Entertainment Weekly.com, “is a fancy way of saying girlfriend was fired.” Not renewing AJ Cook’s contract would mean regular character Jennifer Jareau would have to be written out. Eventually, for what was publicized as financial reasons, CBS also drastically reduced the episode count of Paget Brewster’s character Emily Prentiss for the sixth season. While other women have left the show, I’d like to focus on the season six treatment of AJ Cook, and Paget Brewster’s characters. During the course of the season each character is left with a no-choice-choice that traps them in the womb/brain double bind, and in the end each is punished by losing her position on the investigative team.

For Agent Jareau the womb/brain bind takes the form of family vs. work dilemmas that have plagued her character since she announced her pregnancy at the end of Season 3. Although her pregnancy didn’t seem to have a major effect on her ability to do her job, or travel with the team, once she gave birth to her son, Henry, her character routinely faced these family vs. work conflicts. Until finally, her status as a mother became a reason to question her ability to do her job (was the actress herself pregnant?) Yes the pregnancy was quickly written into the show for her. I think that’s part of why things didn’t get overtly sexist until later.

Agent Jareau’s job as a part of the Behavior Analysis Unit’s team is to choose which cases they will pursue. In the “Mosely Lane” episode of season five her ability to do her job is questioned when she begins to see connections between a recent kidnapping and a case that is 8 years old. As she and Agent Prentiss present the links between the cases to the team, Agent Morgan challenges her by saying, “Have you thought about why you suddenly believe [in the connections]? Do you think it might be because you are a mother?” He, and the other male agents in the room, remain unconvinced the cases are related until Agent Prentiss lays out the similarities, and ends by saying, “…and, I am not a mother.” It is as if Agent Jareau’s status as a mother makes her ability to see connections between the cases suspect; whereas, Agent Prentiss’ status as “not a mother” somehow lends credence to her analysis. Although Agent Jareau has faced difficult choices between work and family in the past, this is the first time her ability to do her job is doubted based solely upon the fact that she is a mother.

The “Mosely Lane” incident is significant because it lays the foundation for the no-choice-choice Agent Jareau must make when she is later forced from the team. The second, and her final, episode of season six is simply titled “J.J.”, Agent Jareau’s nickname. The episode begins with a tense meeting between Agent Jareau, team leader Aaron Hotchner, and his boss, Section Chief Erin Strauss. During the meeting we learn that Jareau has rejected recruitment offers from the Pentagon without letting either Hotchner or Strauss know. As Strauss tries to convince Jareau that the Pentagon is offering her a better job, her primary argument is that, “…there’s less travel with this job, you could stay home with Henry.” The implication being that Agent Jareau’s ability to mother is compromised by the travel required in her current position. By the end of the episode we learn that Jareau has been forcibly transferred from the team to the Pentagon. Since Strauss’ only support for her claim that the Pentagon job would be better was “less travel” and “more time at home,” the course of Agent Jareau’s professional life is now being determined by her personal status as a mother. In the previous season, Agent Jareau’s ability to do her job was questioned because of her role as a mother; and her ability to mother is now suspect because of the travel associated with her job. Forced into taking the promotion, her no-choice-choice is to keep a job by accepting a position she does not want. Therefore, Agent Jareau’s removal from her team can be interpreted as a punishment for attempting to be both a mother and an agent.

Although she is, in her own words, “not a mother,” Agent Prentiss finds herself in a form of the womb/brain bind, and punished by removal from her team. When the two episode arc that marks the end of Prentiss’ presence on the show begins, a case from her past as a CIA operative resurfaces. While undercover to take down an ex-IRA arms dealer, Prentiss becomes romantically involved with Ian Doyle. As her involvement in the case is revealed to the team, we are initially led to believe Doyle, seeking revenge on the woman who betrayed him, is hunting her down. At first it appears that Prentiss’ romantic past, specifically her willingness to use her sexuality to get to Doyle, has come back to haunt her. However, in a series of flashbacks we learn that Doyle revealed the existence of his son, Declan, to her by asking her to take on the role of the boy’s mother. Knowing she is undercover and that the relationship will end when the case is over, she refuses.

In the present as Doyle is about to kill Prentiss, she reveals she has actually compromised her career by acting, like a mother, to protect Declan after his father’s arrest. She explains that she did not tell her superiors of Declan’s existence until she had faked his death. She states, she knew what “they [CIA/Interpol] would do to him” in order to get to Doyle. Prentiss was faced with a no-choice-choice between acting as a surrogate mother to a terrorist’s son (putting herself in danger from Doyle), and acting as an international agent giving him up to the authorities, who she knew would harm him psychologically (at the very least). Prentiss chose to act as a surrogate mother to Declan, protecting him by faking his death, effectively hiding him from his father and the authorities. Choosing to act like a mother in the past is punished in the present when, for her own safety, Prentiss must fake her death and walk away from the job, and team she loves.

That both Agents Jareau and Prentiss are made to leave their team based on either their status as a mother, or their willingness to act like one when faced with a no-choice-choice, is a clear example of the embedded sexism within the show. It is a weekly reminder to professional women that the same double binds they have faced throughout history still apply. They can either be mothers at home, or professionals in the workplace, but not both. The embedded feminism in such dramas, only makes the messages of enlightened sexism that much stronger. Embedding feminism, even if it is primarily through the numbers of women, into dramas like Criminal Minds provides the writers with the opportunity to show the world what real feminist change in the work place could look like, instead of trapping women in the same old double binds.

Afghan Women Fight to Not Have Their Rights Bargained Away in ‘Peace Unveiled’ in ‘Women, War & Peace’ Series

This is a guest post by Megan Kearns. She also contributed reviews of Part 1 and Part 2 of Women, War & Peace.

When I go out of the house in the morning, I say goodbye to my children and my family because I say that I never know if I’m coming alive back home or not.

I am hopeful that my sisters understand the importance of this process…I hope that the Afghan government and, especially, the president, whom women helped elect, do not make a deal that leads Afghan women into miserable lives again.

Women go out with great fear & trepidation. Will there be a suicide attack? Will American tanks or NATO forces fire on people?

When I go out I’m terrified. We are powerless. What kind of government is this? Neither the Americans nor the government rule here. The Americans are on one street and the Taliban on another. They can see each other!

During the time of the Taliban, women endured the worst era. They were imprisoned in their homes, every form of activity in their lives was taken away.

It was the first time that Afghan women came together with Afghan men and discuss peace. Maybe it was even very symbolical but it was like breaking something, like break the culture and impose the presence of women.

Most of these men also make decisions for their wives to whom they should vote. You have to convince them to support women.

The women in Afghanistan are rightly worried that in the very legitimate search for peace, their rights will be sacrificed…None of us can allow that to happen. No peace that sacrifices women’s rights is a peace we can afford to support.

Critically, women’s rights & achievements must not be compromised in any peace negotiations or accords…Women’s experiences of both war and peace-building must be recognized in the peace process.

Girls in Kandahar have had acid thrown in their faces. Girls have been assassinated. They have been kept at home by their fathers. Schools are being burned. In the rural districts, there are no schools at all.

…What astonishes me, what my final issue is that the world community came, saying, “We will work for the people of Afghanistan, especially for the women.” It’s worse than being a dead person in Kandahar. We don’t have a life anymore.

I don’t want to go back. I want to make it easy for my daughters. We will struggle; we will struggle till our last breath. We cannot do anything alone. We are a part of the world. We have to be identified to the world. The world has to support us in this.

Megan contributed reviews of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, The Girl Who Played with Fire, The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest, Something Borrowed, !Women Art Revolution, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, The Kids Are All Right (for 2011 Best Picture Nominee Review Series), The Reader (for 2009 Best Picture Nominee Review Series), Man Men (for Mad Men Week), Game of Thrones and The Killing (for Emmy Week 2011), Alien/Aliens (for Women in Horror Week 2011), and I Came to Testify in the Women, War & Peace series. She was the first writer featured as a Monthly Guest Contributor.

Sunday Recap

Bitch Flicks’ Weekly Picks: pieces from Racialicious, The Crunk Feminist Collective, About-Face, Pandagon, etc.

‘Pray the Devil Back to Hell’ Portrays How the Women of Liberia, United in Peace, Changed a Nation: As the war progressed, the women wanted to take more drastic measures. Inspired by their faith, the women donned white garb to declare to people they stood for peace. Thousands of women protested at the fish market each and every day, a strategic location visible to Taylor. Carrying a huge banner stating, “The women of Liberia want peace now.” It was the first time in Liberia’s history where Christian & Muslim women came together.

Why Should Men Care? An Interview with Matt Damon: “Why I wanted to do Women, War & Peace was because I thought it said something really important about the nature of war and the nature of the experience of women. And—as a guy who’s raising four girls—that matters to me. It matters to me anyway, but that makes it matter to me more.” — Matt Damon

Guest Writer Wednesday: A Review in Conversation of Twin Peaks: We have both admitted to fondness for the more fringe female characters like the Log Lady, Nadine, and Lucy, but they, and all the other women, really only exist according to their relationships with men.

Guest Writer Wednesday: Why Watch Romantic Comedies?: The romantic comedy genre gets a lot of flak. It’s considered a genre that’s more “shallow” than drama, but not funny enough to be a “real” comedy. Is it any coincidence that the romantic comedy is one of the few film genres, and possibly the only film genre, that regularly features women?

Why Facebook’s “Occupy a Vagina” Event Is Not Okay [TW for discussions of rape and sexual assault]: It’s important to note that even the language–occupy a vagina–divorces women from their own bodies. It’s a form of dismemberment, and I’ll say it again: we live in a rape culture, a culture that reduces women to body parts, whether it’s to sell a product, to promote a film, or for nothing more than reinforcing (and getting off on) patriarchal power. When we use language that prevents us from seeing a person as a whole human being, language that encourages us to view women in particular as a collection of body parts designed for male pleasure (e.g. occupy a vagina), then she exists as nothing more than an object, a fuck-toy, sexually available by default. It might not have been the intent of the event creator to participate in women’s subjugation, but it’s certainly the fucking reality.

Swiffer Reminds Us That Women Are Dirt: It’s remarkable how different the portrayals of the dirt people are: the men-as-dirt ads show a Crocodile Dundee-esque character (also stereotypical) and two buddies lamenting the state of their romantic lives, while the women-as-dirt ads always show a lonely, solitary woman desperate for the kind of attention provided by this wonder mop.

Some Scattered Thoughts on Detective Shows and Geniuses: I’m at a bit of a disadvantage in discussing Medium because I’m only familiar with the first season. Perhaps things get better for Allison in later seasons. Perhaps the men in her life stop expressing so much condescension and distrust toward her and endow her with some Lightman- and/or Monk-esque respect. Perhaps she no longer feels compelled to apologize for her own idiosyncratic crime-solving abilities and develops Lightman’s uber-masculine arrogance about it. (But don’t take that confidence too far, Allison—no one wants to work with a bitch.) At the very least, in the first season of Medium, I sort of love her husband. I mean when is a male rocket scientist ever the sidekick, hmmm?

Why Should Men Care? An Interview With Matt Damon

|

| Matt Damon narrating Women, War & Peace |

Guest Writer Wednesday: Why Watch Romantic Comedies?

|

| some romantic comedies |

This guest post by Lady T previously appeared at her blog The Funny Feminist.

I also think that looking at romantic comedies is a worthwhile feminist project. I want to look at how men and women are represented in these films. I want to look at the way romantic expectations are presented in our popular culture. I want to look at issues of consent. I want to look at the way the comedy genre affects the romance genre and vice-versa.

For the parody or spoof film genre, the entry lists three examples. 0 of 3 of these examples have female protagonists.

For the anarchic comedy film genre, the entry lists two examples. 0 of 2 of these examples have female protagonists.

For the black comedy film genre, the entry lists fourteen examples. 1 of these 14 examples (Heathers) has a female protagonist without a male co-protagonist, and fewer than half have a female co-protagonist.

I think you can all start to see the pattern here, but let me continue just to belabor the point.

Action comedy films. 9 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Comedy horror films. 9 examples, 1 female protagonist (in Scary Movie).

Fantasy comedy films. 6 examples, 2 female co-protagonists (The Princess Bride, Being John Malkovich), 0 female protagonists without male co-protagonists.

Black comedy films. 3 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Sci-fi comedy films. 8 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Military comedy films. 9 examples, 1 female protagonist (Private Benjamin).

Stoner films. 4 examples, 0 female protagonists.

Some might argue with me on particular examples, but it’s obvious that dominant characters in comedy films are overwhelmingly male. (I also understand that Wikipedia is not an entirely accurate source of information, but the examples that are used to represent these different genres explains a lot about our cultural attitudes.)

If you look at the entry on romantic comedies, you see many more films that have female protagonists, or at least female co-protagonists. Especially significant is the list of top-grossing romantic comedies. 22 films are listed. More than half of them have female co-protagonists, some have one female protagonist, and one has (gasp!) more than one female protagonist (Sex and the City).

—-

Why Facebook’s "Occupy a Vagina" Event Is Not Okay

Last week, a Change.org petition urged Facebook to remove pages that promote sexual violence. Some of the offending pages included, “Kicking Sluts in the Vagina,” and “Riding your Girlfriend softly Cause you dont want to wake her up.” The following passage from the petition explains the overall goal:

First, Facebook needs to clarify that pages that encourage or condone rape–like the ones mentioned above–are in violation of their existing standards. Secondly, they need to make a statement that all pages that describe sexual violence in a threatening way will be immediately taken down upon being reported. Finally, Facebook must include specific language in their Terms of Service that make it clear that pages promoting any form of sexual violence will be banned.

In some ways, misogyny on Facebook is just a newer version of the same old problem. Indeed, there are enough stories like Sierra’s for Danielle Citron, a cyber law professor at the University of Maryland, to compile a whole book of them—she’s hard at work on a text about online harassment that will be published by Harvard University Press in 2013. She notes more recent cases that have made headlines: the women smeared by AutoAdmit, the law school discussion board; the case of Harvard sex blogger Lena Chen; and the dramatic story of 11-year-old Jessi Slaughter. “I talk to women every day who’ve been silenced, scared, and just want to disappear,” Citron says. “It’s easy to dismiss these things as frat-boy antics, but this isn’t a joke.”

With zero tolerance for porn and a refusal to define it, Facebook has deleted breast cancer survivor communities (labeling one breast cancer survivor page as “pornography”), retail business pages, individual profiles of human sexuality teachers, pages for authors and actors, photos of LGBT couples kissing (for which Facebook just apologized), and even the occasional hapless user’s profile who has the misfortune of having someone else post porn on their Wall.

With no comprehensible or clear methodology around sexual speech, we see pages deleted that discuss female sexuality, while pages that joke about and encourage raping women and girls rack up the likes.

(Edit for all the trolls)

*************

To all of you people who want to assume this event has anything to do with rape, you are completely wrong… This event was created by a WOMAN as a JOKE!!! If you don’t think it is funny, then click not attending and move on… I will be deleted any trolling ass messages about “promoting anything” other than comedy so don’t waste your time……

According to the rape culture theory, acts of sexism are commonly employed to validate and rationalize normative misogynistic practices. For instance, sexist jokes may be told to foster disrespect for women and an accompanying disregard for their well-being. An example would be a female rape victim being blamed for her being raped because of how she dressed or acted. In rape culture, sexualized violence towards women is regarded as a continuum in a society that regards women’s bodies as sexually available by default.

…This constant, unchecked barrage of endless and obvious woman-hating undoubtedly contributes to the rape of women and girls.

The sudden idealization of Charlie Sheen as some bad boy to be envied, even though he has a violent history of beating up women, contributes to the rape of women and girls. Bills like H. R. 3 that seek to redefine rape and further the attack on women’s reproductive rights contributes to the rape of women and girls. Supposed liberal media personalities like Michael Moore and Keith Olbermann showing their support for Julian Assange by denigrating Assange’s alleged rape victims contributes to the rape of women and girls. The sexist commercials that advertisers pay millions of dollars to air on Super Bowl Sunday contribute to the rape of women and girls. And blaming Lara Logan for her gang rape by suggesting her attractiveness caused it, or the job was too dangerous for her, or she shouldn’t have been there in the first place, contributes to the rape of women and girls.

It contributes to rape because it normalizes violence against women. Men rape to control, to overpower, to humiliate, to reinforce the patriarchal structure. And the media, which is vastly controlled by men, participates in reproducing already existing prejudices and inequalities, rather than seeking to transform them.

It’s unfortunate that I need to add to this:

Facebook’s refusal to ban all pages that condone sexual assault and violence against women, and their refusal to acknowledge that these pages violate their already existing standards, contributes to the rape of women and girls.

Some Scattered Thoughts on Detective Shows and Geniuses

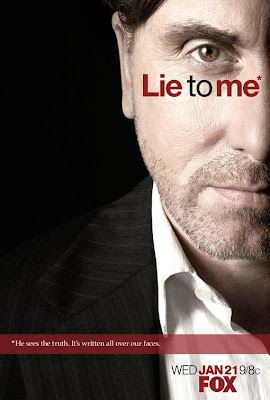

After an episode of Monk, I spend some time with Cal Lightman from Lie to Me, a current show in its third or fourth season that centers around an agency called, The Lightman Group, which specializes in reading facial expressions. Apparently, we all have these things called “micro-expressions” that betray us when we’re lying, but only highly-trained people can catch and decode these micro-expressions, (e.g. the employees at The Lightman Group). Dr. Lightman is literally a human lie detector, and it’s fun to watch him get up in the faces of liars and act like a cocky British bad-ass. He, too, works with women who, while brilliant and talented in their own right, spend a significant amount of their screen-time playing sidekick to Lightman and cleaning up his messes.

All this boy drama started to become stifling, so I browsed Netlix and found Medium (which first aired in 2005), a show I’d seen a few episodes of—and liked—but that I never really pursued, probably because of my embarrassing fear of the occult. Medium centers around Allison DuBois, a woman who can communicate in various ways with the dead, and who also has some psychic ability, such as knowing when a person might die, or experiencing creepy flashes of the horrible shit people have done in their pasts. DuBois interests me because, in addition to holding a job as a consultant for the district attorney (similar to Monk’s role in some ways) she’s also a mother of three young girls and has a rocket scientist husband who gets fed up on a regular basis with her mind-reading, afterlife communing talents. He admires her crime-solving abilities but deep down wishes she’d continued to pursue her law degree instead, in the name of normalcy. In this show, the man slash husband plays sidekick.

These three detective characters are similar in that their main role on their respective television shows is to catch criminals. All three of them aid the police force. All three of them often endanger themselves in the process of tracking down criminals. All three of them always succeed (which is the formula for crime dramas), and we’re led to believe that the criminals wouldn’t have been caught without the help of these characters. Monk, for instance, even with all his quirks and the accommodations he requires, is hailed as an absolute genius by his colleagues and is constantly referred to as “the greatest detective in the world” by his assistant. And he is, in fact, a scary good detective, and it’s for that reason that his quirks and his often abusive behavior (while played for laughs) is forgiven—the audience is led to believe that Monk wouldn’t be a genius detective without these eccentricities. (An episode where Monk takes an antidepressant for his phobias and subsequently becomes useless as a detective confirms that theory.)

Cal Lightman, too, might be one of the most egotistical characters I’ve seen on television, and he’s immensely likeable. He breaks all the rules and consistently does pretty much the opposite of what anyone tells him to do. His lack of respect for authority often helps him win his cases; his immediate contempt for and suspicion of The People in Charge sends him in unusual directions to solve crimes, so the audience is treated to episodes where he (hilariously) and deliberately does things like checking himself into a mental hospital, or going undercover as a coalminer and threatening to blow up the place if he doesn’t get answers—but we, and his colleagues, respect him more for his unorthodox detective work. Yes, he may step all over the people around him, but that’s just how he does things; who are they to get in the way of a genius in his element? But Cal inevitably leaves some sort of mess behind when he operates outside the box (i.e. pisses off so many authority figures), and it’s no surprise that his colleague, Dr. Gillian Foster, a psychiatrist who partnered with him to start The Lightman Group, gets stuck making amends on his behalf. (I’m very much reminded of the Dr. House/Dr. Cuddy dynamic here from the television show House.)

Interestingly (or not), both Monk and Lightman find motivation and success in their careers because of dead women; Monk is literally obsessed with finding Trudy’s killer (which is the one crime he hasn’t been able to solve), and Lightman wasn’t able to save his mother from killing herself; he watches old video tapes of her, repeatedly pausing them to read and reread her micro-expressions. This “I’m avenging the death of my [insert relationship to woman here]” theme shows up in, like, every movie about a man who achieves anything. In these shows and movies, even the dead women exist as nothing more than plot points to drive the narrative forward. It’s sick and demeaning to women. In fact, I should make a list of the films and television shows in which this trope exists and call it the “I’m Avenging the Death of My [Insert Relationship to Woman Here] Trope.” (I’m doing it.)

Did you think I forgot about Mrs. Allison DuBois? I love her. And oh what a difference gender makes on a detective show. In her world, she’s successful not because she’s eccentric or because she has a god complex but because she has special powers. In her world, even though she solves case after case, and sheds new light on past cases, she must always fight to be taken seriously by her boss, by her family, and often by her husband. The audience watches DuBois struggle both with solving the cases (while trying to raise a family of young daughters and keep her marriage intact) and dealing with the way her job directly impacts her interpersonal interactions. She isn’t, as is the case with Monk and Lightman, surrounded by an endless network of supportive characters no matter what; instead, her kind of “genius” is scary and unnatural and not to be trusted.

I get it. Dead people tell her shit, which is a little different than being aided by obsessive-compulsive disorder and a lucky mixture of intelligence coupled with extreme arrogance and defiance. But DuBois must decode the messages she gets, too. A dead person doesn’t just show up and say, “Hey, that dude killed me, and my body’s buried behind that dude’s house over there. Find me. Thanks.” The occult is obviously way more complex than that (eek!). While Lightman and Monk find themselves surrounded by people who worship them, she deals with the extra struggle of convincing people she isn’t crazy—but like, how many cases does she have to solve before people just admit she’s fucking awesome?

Arguably, DuBois is a much more fleshed-out character than Lightman or Monk. She has a husband, a family, a career, unacceptable sleep patterns, daycare to deal with, a possible alcohol problem, parent-teacher conferences to deal with—a life! The men, though, just kind of do the same shit every episode. Lightman does, however, have a teenage daughter, and season two ends with him flipping out about his daughter losing her virginity. I’m not joking. That’s how the entire season ends—in an episode where Lightman gets upset about his daughter not being a virgin anymore. I’m serious. It’s called “Black and White,” and it’s a horrible episode. (Seriously.)

I’m at a bit of a disadvantage in discussing Medium because I’m only familiar with the first season. Perhaps things get better for Allison in later seasons. Perhaps the men in her life stop expressing so much condescension and distrust toward her and endow her with some Lightman- and/or Monk-esque respect. Perhaps she no longer feels compelled to apologize for her own idiosyncratic crime-solving abilities and develops Lightman’s uber-masculine arrogance about it. (But don’t take that confidence too far, Allison—no one wants to work with a bitch.) At the very least, in the first season of Medium, I sort of love her husband. I mean when is a male rocket scientist ever the sidekick, hmmm?

I guess ultimately what concerns me about these portrayals of male and female detectives is that it mirrors real life. Men are geniuses. It’s a fact. I think I once heard someone refer to Sylvia Plath as a genius in a lit class, but it’s absolutely uncommon to hear a woman referred to as such. Being a (male) genius comes with perks, too. You’re forgiven your bullshit, your weirdness, your unorthodox behavior, your screw-ups, your law breaking. I always think specifically of Roman Polanski—a film director who drugged and raped a 13-year-old girl, never went to prison, and managed to garner support from thousands in Hollywood who signed a petition on his behalf. He’s a genius! He’s paid his dues! Let him come back to the U.S.!!!!! I also recall the outrage surrounding the Julian Assange rape accusations—men across the globe immediately came to his defense (including “liberals” Michael Moore and Keith Olbermann), arguing: It’s a setup! Those women are lying! He’s a genius! Kneel before Zod!

Even though I really want to end this post on the phrase “Kneel before Zod!” I’d also like to say that while I love DuBois and think she is a genius and want to see her treated as such (in the same manner as her male counterparts) I’d also love to see more regular-ass women characters achieving genius-level shit. We need and love our women with superpowers (Buffy, too, of course), but I personally want to see a woman who looks like me, who does weird and unacceptable shit like me, who sometimes goes out in public wearing sweatpants like me, achieving some genius-level shit. I truly believe, as someone who studies pop culture and media, that we’re not going to make much progress toward ending misogyny in our everyday lives if we don’t deal with the misogyny we’re bombarded with in television shows, music videos, advertisements, films, and children’s programming. If we see it reflected all around us constantly, it becomes the norm. So, we need to call this shit out and keep calling it out, even when it seems like a tiny thing—like douchebag male detectives with unorthodox methods getting a free genius pass while brilliant female detectives with unorthodox methods have to endlessly prove their competence to significantly less competent people.

That right there is fucking patriarchy in action. Now:

Bitch Flicks’ Weekly Picks

“Tilda Swinton: I Didn’t Speak for Five Years” by Kira Cochrane for The Guardian

“Are TV Ads Getting More Sexist?” by Derek Thompson for The Atlantic

“Painful Baby Boom on Prime-Time TV” by Neil Genzlinger for The New York Times

“The Rebirth of the Feminist Manifesto” by Emily Nussbaum for New York Magazine

“Sexy or Sexism? Redefine Sexy, Identify Sexism” from SexyorSexism.org

“Diverse Black Women Dominating Daytime TV” by Ronda Racha Penrice for The Grio

“Chapstick Sticks It to Women” by Melissa Spiers for ReelGirl

“‘How to Be a Gentleman'” Cancelled” by James Hibberd for Entertainment Weekly

“Is She Really With Him?” by Molly McCaffrey for I Will Not Diet

“We’ll Always Be Together: Girl-Gang Style in Movies” by Marie for Rookie Magazine

I Feel Like Hell …

—

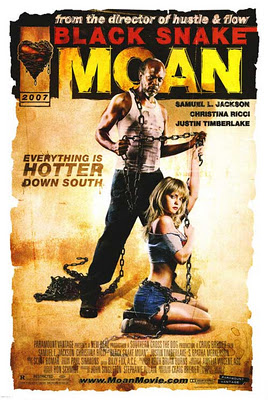

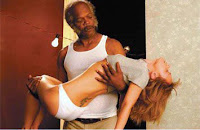

In Mississippi, the former blues man Lazarus is in crisis, missing his wife that has just left him. He finds the town slut and nymphomaniac Rae dumped on the road nearby his little farm, drugged, beaten and almost dead. Lazarus brings her home, giving medicine and nursing and nourishing her like a father, keeping her chained to control her heat. When her boyfriend Ronnie is discharged from the army due to his anxiety issue, he misunderstands the relationship of Lazarus and Rae, and tries to kill him. (Claudio Carvalho)

This is a movie that I want to love. It’s gritty, unique, and aware of class and race—a rare combination. However, there is no female perspective in the movie. Is it really too much to ask for a sharp film to also be sharp about gender? Is it right for a film like BSM to claim gender as a theme, while not really exploring women at all? Rae is the only female character (brief appearances by Lazarus’ wife, Rae’s mother, and a kind pharmacist easily fit into the angel/monster dichotomy), but she isn’t quite a real person. What is wrong with her? She is talked about as a nymphomaniac, and has strange, demonic fits of desire, but she’s really a victim of rape and abuse. Lazarus, whose trauma is that his wife aborted his baby and left for his younger brother, takes it upon himself to “cure” her by chaining her to a radiator. Even if the movie isn’t to be taken literally (but as a metaphor of sorts), why are the other characters so human and she so other, so animal?

This is a movie that I want to love. It’s gritty, unique, and aware of class and race—a rare combination. However, there is no female perspective in the movie. Is it really too much to ask for a sharp film to also be sharp about gender? Is it right for a film like BSM to claim gender as a theme, while not really exploring women at all? Rae is the only female character (brief appearances by Lazarus’ wife, Rae’s mother, and a kind pharmacist easily fit into the angel/monster dichotomy), but she isn’t quite a real person. What is wrong with her? She is talked about as a nymphomaniac, and has strange, demonic fits of desire, but she’s really a victim of rape and abuse. Lazarus, whose trauma is that his wife aborted his baby and left for his younger brother, takes it upon himself to “cure” her by chaining her to a radiator. Even if the movie isn’t to be taken literally (but as a metaphor of sorts), why are the other characters so human and she so other, so animal? Response by Stephanie

Later though, after Lazarus “cures” her by wrapping a giant chain around her waist and attaching it to a radiator, Rae is allowed to enter society again, showing up at a bar with Lazarus, drinking, rubbing up against everyone on the dance floor while Lazarus watches her from the stage, almost approvingly. What’s going on here? I truly want to read this as much more complicated than a man giving a woman permission to flaunt her sexuality, and I think it is.

Later though, after Lazarus “cures” her by wrapping a giant chain around her waist and attaching it to a radiator, Rae is allowed to enter society again, showing up at a bar with Lazarus, drinking, rubbing up against everyone on the dance floor while Lazarus watches her from the stage, almost approvingly. What’s going on here? I truly want to read this as much more complicated than a man giving a woman permission to flaunt her sexuality, and I think it is.

Response by Amber

But back to the way gender and sex intersect. If nymphomania is itself largely fictitious, the strange way Rae’s fits were portrayed—moments in the film that were suspended between fear and comedy—reveals some of the ideological confusion of the film. If not for her nearly-naked body, battered and bruised and constantly displayed, I might have more sympathy for the film’s motivations. Add that to Rae’s moment of catharsis where she beats the shit out of her mother with a mop handle (for allowing Rae to be raped, either by her father or another male figure in her home), and we see women destroyed by sex who we’re supposed to sympathize with.

But back to the way gender and sex intersect. If nymphomania is itself largely fictitious, the strange way Rae’s fits were portrayed—moments in the film that were suspended between fear and comedy—reveals some of the ideological confusion of the film. If not for her nearly-naked body, battered and bruised and constantly displayed, I might have more sympathy for the film’s motivations. Add that to Rae’s moment of catharsis where she beats the shit out of her mother with a mop handle (for allowing Rae to be raped, either by her father or another male figure in her home), and we see women destroyed by sex who we’re supposed to sympathize with.

Response by Stephanie

In that moment of catharsis with her mother, I found myself detached. Instead of sympathizing with Rae and coming to some kind of realization myself, I just rolled my eyes at the ridiculous, clichéd consequences of her abuse—girl gets raped by father-figure while mother does nothing to stop it, girl develops low self-esteem, girl becomes town slut, girl develops a fictional sex disease, girl gets chained to radiator by religious black man. Wait, what? Ah religion, how you never cease to reinforce the second-class citizenship of women, perpetually punishing them for their godless desire to fuck.

In that moment of catharsis with her mother, I found myself detached. Instead of sympathizing with Rae and coming to some kind of realization myself, I just rolled my eyes at the ridiculous, clichéd consequences of her abuse—girl gets raped by father-figure while mother does nothing to stop it, girl develops low self-esteem, girl becomes town slut, girl develops a fictional sex disease, girl gets chained to radiator by religious black man. Wait, what? Ah religion, how you never cease to reinforce the second-class citizenship of women, perpetually punishing them for their godless desire to fuck. I’m not writing from a place of progress. I’m not writing a movie that I want people to necessarily intellectualize. And I think that really messes with people who feel that they need to make a statement against this, and they don’t quite know what it is they’re against. Because man alive, you look at this imagery on this poster, and I’m so obviously banging this drum. It’s like, you really believe that I believe this? That women need to be chained up? Can we not think metaphorically once race and gender are introduced?

Guest Writer Wednesday: Where Do We Go Now?

|

| Arabic movie poster for Where Do We Go Now? |

—

Call for Writers: Animated Children’s Films

|

| Red from Hoodwinked Too |