|

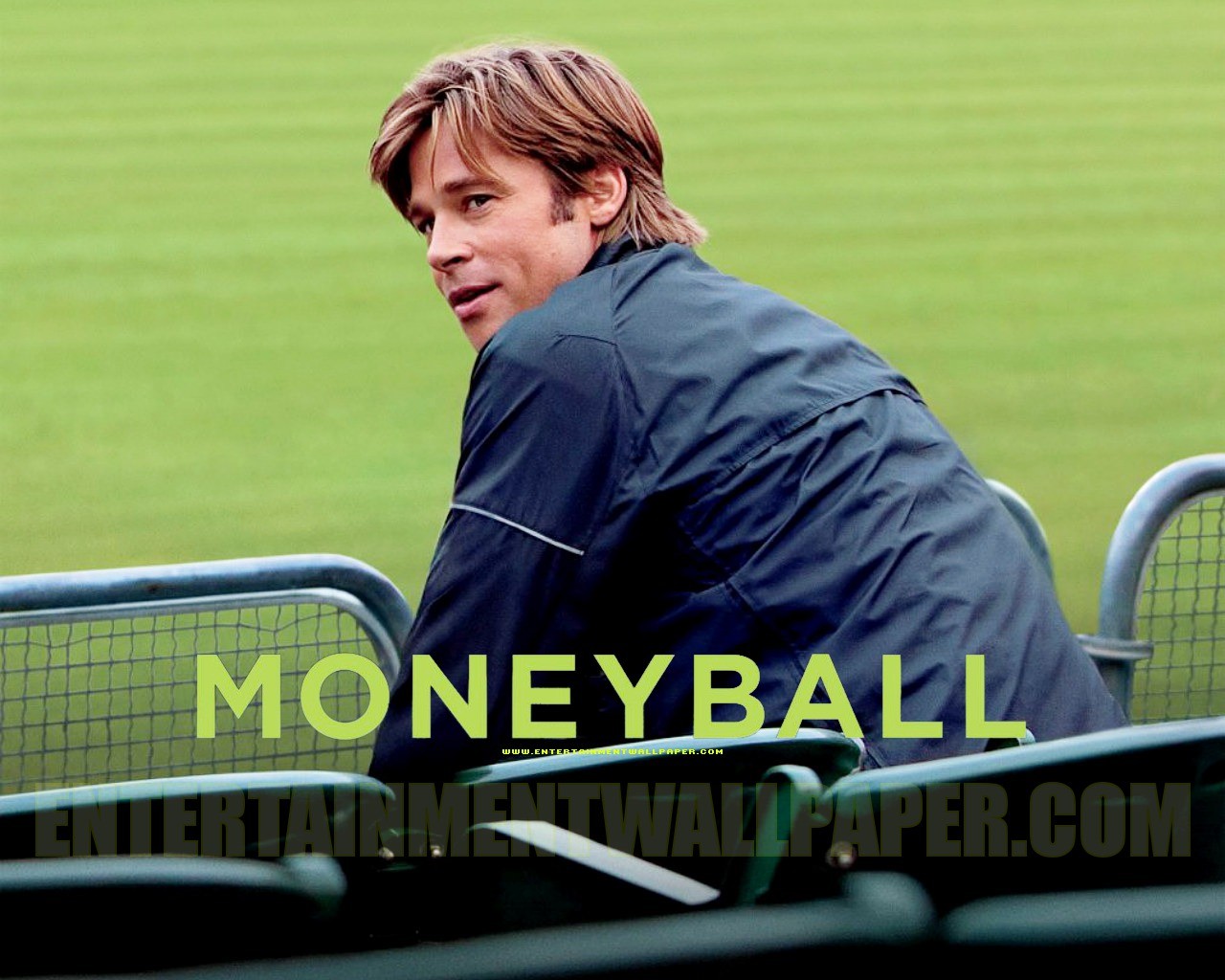

| Justine as Ophelia? from Melancholia (2011) |

This is a guest post from Hannah Reck.

“All say, ‘How hard it is that we have to die’—a strange complaint to come from people who have had to live.” –Mark Twain

As a mother of a 3-year-old, I don’t get out much, and, on my evenings off, I’d rather lie on the couch and watch something mindless. Sad, but true. A friend asked me to meet her at the town’s indie film theater and I knew nothing about the film I was going to see, not even the name…or director. I am not well-versed in Lars Von Trier’s work; though, I did try to watch

Dancer in the Dark and couldn’t make it through. The film we saw is obviously

Melancholia. I’d never even seen a trailer for this film and I left the theater thinking, “how could you ever make a trailer for

THAT?!?” Afterward, I watched

the official trailer and thought it simplified what was so moving about this film. Yes, it’s about the end of the world, but it’s so much more than that.

Ultimately, Melancholia is about the human condition and how we handle the deep emotion we feel and our personal definition of crisis. The film centers on the relationship between two sisters, who react differently to life’s challenges, and in this case they deal with life’s biggest challenge: death. Not only a single death, but death of everything, which is, I don’t know, kind of heavy. Justine, played brilliantly by Kirsten Dunst, is a near-debilitated depressive who forms a strange relationship to the approaching planet Melancholia. Claire, (Charlotte Gainbourg) is the other sister, very much the antithesis of Justine. For one, she’s sane and copes with life according to the rules of society; employing the niceties by which we all try to abide. Justine doesn’t. Even at her wedding, she rejects the ritual and falls into a deep depression after her mother’s toast. Their mother Gaby, a cutting and steely woman, is played by Charlotte Rampling (always brilliant), and their father Dexter, a bumbling, well-meaning drunk, by John Hurt (sometimes brilliant). Claire, it seems, has helped her sister cope with her depression throughout her entire life. Despite Justine’s episodes, Claire plans an extremely lavish wedding for her sister in the home she shares with her husband (Kiefer Sutherland) and her son, Leo (Cameron Spurr). Their home screams Gothic Romanticism, and could easily be the set of a British period drama with a brooding Byronic hero gazing down from the window. Justine is that hero…Byron-esque heroine?

|

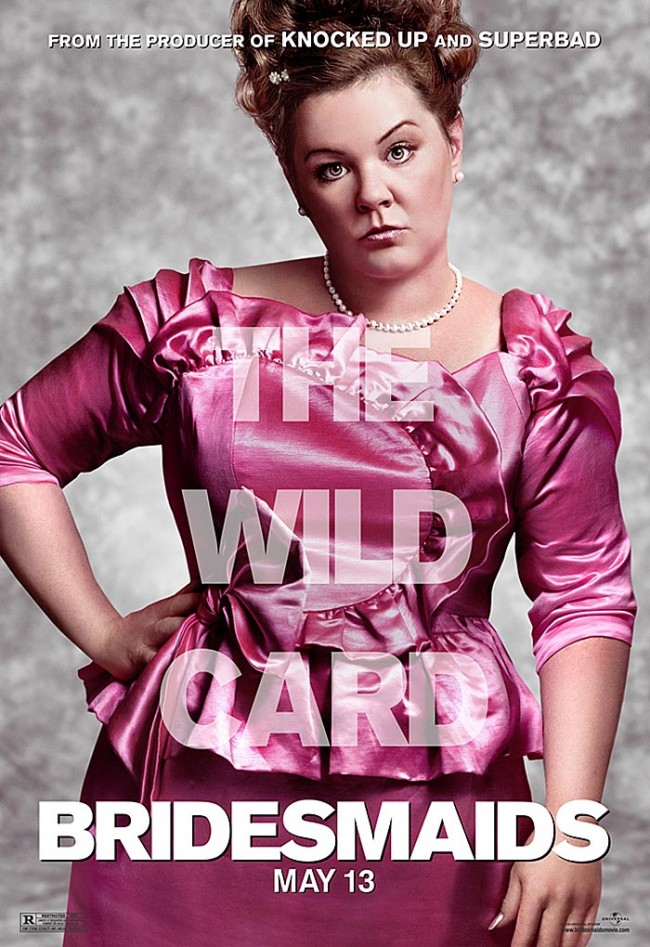

| Justine, Leo, and Claire |

Melancholia possesses qualities of romanticism, which Merriam-Webster defines as: a predilection for melancholy, and Wiki describes as “strong emotion as an authentic source of aesthetic experience [with] emphasis on such emotions as trepidation, horror and terror and awe—especially that which is experienced in confronting the sublimity of untamed nature and its picturesque qualities.” Where Melancholia is concerned, this is an exact description. Though I didn’t grab this Romantic connection immediately, the painting by Casper David Friedrich (most famously associated with Romanticism), Wonderer above the Sea and Fog, reminds me of the film in so many ways. The cinematography possesses the same overcast and pallid blueness that creates the moodiness in Friedrich’s painting. Justine, the main character, is seen looking out onto the vastness of the sea, the glorious grounds and into the infinity that is the sky: the sublime.

|

| Casper David Friedrich’s Wonderer above the Sea and Fog |

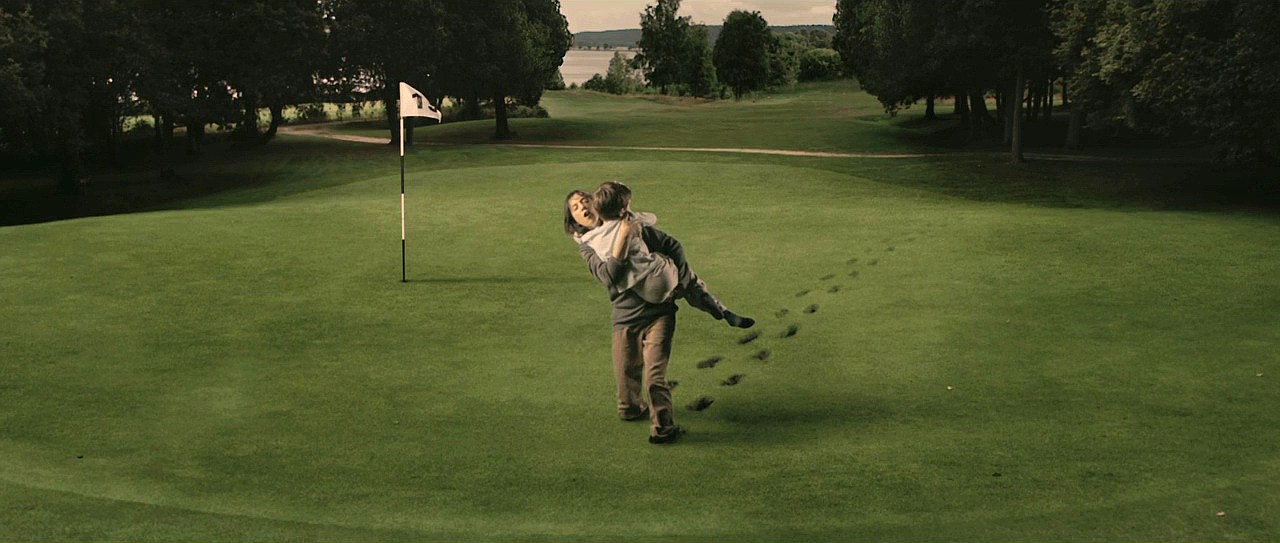

Melancholia, the planet, is surely sublime. No has before, or will again, experience the super-planet’s awesomeness and the inhabitants of Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia have days to wonder about the vastness of our galaxy and how small we actually are in relation.

Von Trier admits he did not set out to make a Romantic film, but it became one over time. He uses Robert Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde as the haunting theme for the film. When I’ve re-viewed parts of the film the music triggers a physical emotion, because I felt a real connection to the melancholic aspects. Everyone suffers from some degree of depression and I felt an almost-sigh of relief that depression of this magnitude was shown so intimately in a motion picture. I was able to sympathize with Justine’s condition, despite her selfishness. That’s not to say that she isn’t a strange character that could be called crazy. Melancholia takes an almost supernatural turn as Justine becomes Melancholia’s advocate and justifies its course toward earth. “I know things,” she says, “the earth is evil. We don’t need to grieve for it. Nobody will miss it.” Claire is baffled, “How do you know?” “Because, I know things,” Justine says, “And when I say we’re alone, we’re alone. Life is only on earth, and not for long.” It’s a creepy scene, but somehow you believe it without knowing why. Also, she moon-bathes nude (Melancholia-bathes) in a spot just off the property, which is Dunst’s second nude scene. Some people moon-bathe because it’s supposed to revitalize you and give you energy, and Justine’s visit to this spot is the one time she looks truly happy, excited even—I would go as far as sexually excited. Gazing up at the new sight of Melancholia, she softly caresses her skin as though she’s looking into her lover’s eyes and she smiles. Perhaps, she wants to die so badly, that this is the answer to her prayers…?

Claire, distraught, as any person with something to lose, grieves for her son who will never grow up. Though this is the main motivation behind her upset, I found her mothering abilities lacking in their final days. As Melancholia enters their atmosphere on their last day, her son falls asleep because they are losing oxygen. She lays him down in his bed and leaves the room to talk with Justine. As a mother, I found this strange. What if he died? What if he was breathlessly calling for her? It disturbed me. Also, when she finally realizes that Melancholia will indeed hit, she goes to find John, who has taken all the pills she has prepared to softly lull her family into death’s arms. She finds him dead, in their stable, and her reaction is strange. She feels sad (okay) and dwells next to him, almost forgiving what he’s done, and remains there for what seems like an eternity. Yes, it would be upsetting to find your husband dead, but come on—he’s left you (and your child) to meet the end alone. He’s a coward, like most of the men in the film, and this illustrates that Von Trier seems to empathize much more with the women in the film. They are written as the source of power when it really counts.

|

| Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow |

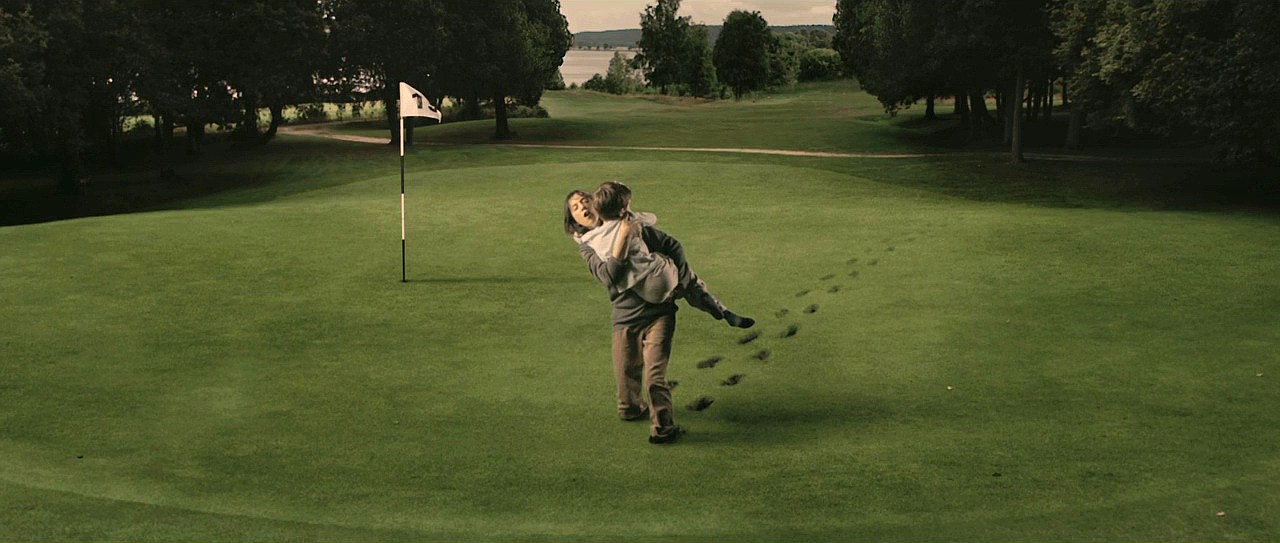

Melancholia is divided into three parts: the introduction, “Justine,” and “Claire.” The intro is a sequence of slow-motion scenes and still images that lasts for 8 (long) minutes, the gist of which is a strange synopsis of the film’s action; however, some of the images never actually play out. The audience sees a dirty, dead-eyed, close-up of Justine in the yard looking into the abyss, while birds fall silently (dead) from the sky. We see her teaching Leo how to sharpen stick with a knife, for the magic cave she’s promised to build. The stills look a bit like she’s teaching him to hunt, which seems connected to Bruegel’s painting, Hunters in the Snow. Not only does this work illustrate the vastness of nature, it shows (like the Romantics) the micro and macro of the landscape (and the hunter’s sticks like the ones they prepare). This image repeats in the film and is the third frame in the opening; first the still painting and then it begins to slowly burn. Pretty sad really, to think of–All. Art. Gone. Every masterpiece, gone in an instant— this, oddly, made me saddest of all. Also in the intro, (never actually seen) Claire in utter panic, running with Leo as her legs sink into the ground. Half of the images are of Justine, Leo and Claire in wedding attire, at the ready, with a grand, gothic estate behind them. Oh, and Melancholia crashing (slowly) into the earth—and it’s truly beautiful.

|

| Claire running with Leo |

Justine and Claire could be viewed as one person, because their roles completely reverse by the end of the film, illustrating that we all possess the same characteristics but utilize them at different times. Hate to say it, but (some) depressives are quite good in a crisis. They can put their immediate problems aside and deal with much larger themes (yes, I’m saying me). Justine is a wreck in “Justine,” and Claire appears stable (while John is still alive), but in “Claire,” she falls completely apart and Justine is very strong. Leo calls Justine “Auntie Dealbreaker” in “Justine,” when she keeps wandering off from her wedding reception and breaks her deal with John to smile, be happy, and go through with the wedding she’s promised will make her happy (at the wedding that he’s paying for). Leo calls her “Auntie Steelbreaker” in “Claire” because she’s so tough she could break steel? I think “Justine” demonstrates Justine’s deterioration (possible pre-grieving her death) that is brought on by Melancholia’s relationship to the earth. Though this is (oddly) never discussed in the film, she falls apart as Melancholia begins its “death dance,” and reenergizes when it lines up to hit us directly. Much to John’s chagrin, Claire finds a diagram, on the internet, illustrating the orbital “death dance” Melancholia will take (it comes close, moves away and then comes back and hits).

|

| Melancholia approaches |

The men of Melancholia run away and are dismissive of women’s emotion. Justine’s father leaves on her wedding night (even though she begs him to stay); he seemingly cannot deal with her melt-down (and is also self-centered). Her new husband, Michael (played by Alexander Skarsgard), leaves when she won’t consummate their marriage (seemed hasty). Her boss (Stellan Skarsgard, Alexander’s dad, by the way) throws a royal fit when she won’t deliver the tagline he’s forced his nephew, Tim (Brady Corbet), to hound her about all night. She quits her job, as a high-powered ad exec, and (our only moment of true clarity about Justine’s past) pinpoints, with cutting accuracy, why she despises his vapid character and profession. He throws a raucous tantrum (plate-throwing) and leaves. John is completely dismissive of Justine’s feelings/depression (somewhat founded, she is pretty self-absorbed) and his wife’s relentless support; but moreover, he completely trivializes her fear of Melancholia. Instead of facing death with her and admitting he is wrong, he kills himself and leaves his wife and son to suffer a horrible, fiery death. Von Trier wrote these characters, and while he may not have intended for the men to come off as cowardly weaklings, they do.

Finally, here’s my big issue with the film: clarity. Did Von Trier purposefully remain ambiguous? Yeah, probably. Okay, what was Justine like before? She has bridesmaids, but never talks to them. She has a fiancé, who was really excited about marrying her—and they seem really in love, so she can’t have always been this bad. She has a career, as a high-powered ad executive that her boss says, “is the best in the business.” Wouldn’t that require a certain degree of responsibility? I needed more here. How are we to believe that she could hold a job and have friends if she’s a fucking unapologetic wreck all the time? AND—no one remarks that she’s behaving differently—is she worse than normal? Is old Justine at it again…? Yes, on her wedding night her sister says, “we talked about this, no episodes tonight,” but people seem to believe in her. Michael gives the sweetest speech about his love and devotion to making her happy. I’m not being sappy here; his toast to her is a really fine piece of acting.

Overall, a provoking film that forces you to think about the character’s point-of-view. Von Trier is a controversial character himself; he is eccentric and admittedly made this film about his own depression. Possibly fueled by the whole 2012 phenomenon, I’d say he’s made (so far) the most beautiful and compelling film about the end of the world.

|

| Melancholia approaches Earth |

Hannah Reck is a professional undergrad who has gained a lot of knowledge in a variety fields: Acting, Musical Theater, Women’s Studies, English, and Secondary education from Ithaca College, CCM and the University of Cincinnati. She’s taken time off to marry, have a baby and a kidney transplant.

and

and  . She’s published work in American Poetry Review, Ploughshares and The Best American Poetry series. She was awarded an NEA Fellowship in 2001 and a Breadloaf Fellowship in 2009. She has taught at UC Irvine and the University of Redlands and is a regional branch manager for OC Public Libraries in southern California.

. She’s published work in American Poetry Review, Ploughshares and The Best American Poetry series. She was awarded an NEA Fellowship in 2001 and a Breadloaf Fellowship in 2009. She has taught at UC Irvine and the University of Redlands and is a regional branch manager for OC Public Libraries in southern California.