|

| Dirty Dancing poster |

This is a guest review by Myrna Waldron.

I was less than a year old when Dirty Dancing came out. It is known for the chemistry between its stars, incredible choreography, and a fantastic soundtrack that balances the sounds of the 60s and the 80s. It’s a typical coming-of-age story, but one of the less-discussed plot points in the film is how it approaches the consequences of an unintended pregnancy during a time in which abortion was still illegal (The film takes place in 1963). As a lifelong fan of the film, Dirty Dancing was my first introduction to the issues of abortion. The film is incredibly progressive in its depiction of Penny Johnson (Cynthia Rhodes), a dancer forced to face the most difficult of decisions, and makes a very strong illustration of the consequences of illegal abortions.

In her introductory scenes where she is dancing a mambo with the main love interest, Johnny Castle (Patrick Swayze), Penny explodes on the screen as a vision of raw sexuality and incredible talent. Frances “Baby” Houseman (Jennifer Grey) is instantly awed and envious of Penny’s dancing abilities, and attempts to befriend her. One of the major themes of Dirty Dancing is its class distinctions, and the dancers are under especially strict orders from their boss not to get too close to the wealthy families staying at the resort. Penny’s responses to Baby are thus aloof, but she still reveals a tremendous amount of background information; Penny’s mother kicked her out of the house at 16, and she has been dancing ever since because it was the only thing she ever wanted to do. Penny has thus been established as someone of low income, with no familial support. The subtext of Penny’s backstory is that dancing for her is her only means of income; she does not see herself as having any other abilities.

|

| Cynthia Rhodes as Penny Johnson in Dirty Dancing |

When Penny’s pregnancy is discovered, she is shown curled up in a darkened corner, shivering and sobbing. Her only friends at the resort, Johnny and his cousin Billy, instantly figure out what is wrong just from Baby’s report of Penny’s frightened and desperate state. It is an important aspect of Penny and Johnny’s characters that, despite the intense sexuality of their dance routines, they maintain a sibling-like platonic relationship. As Johnny goes to Penny’s aid, he mutters, “Penny just doesn’t think.” Despite this statement coming from a loved one, Johnny’s reaction mirrors a common sentiment that women should bear all the blame for an unintended pregnancy, that not getting pregnant is their responsibility alone. However, when he finds her, he tells her “I’m never gonna let anything happen to you,” showing that despite his angry outburst, he cares about her enough to give any assistance that he can.

Johnny offers the last of his salary to pay for Penny’s abortion. Notably, the option for keeping the baby or giving it up for adoption is never discussed. There are several reasons for this. First and most obviously, Penny cannot continue the strenuous dancing routines if she is pregnant. She would lose her sole source of income, and would have nothing to pay for care for herself or the baby. Second, if news of her pregnancy gets out, she would be instantly fired, and would lose the important reference that working at the resort gains her. Third, the father is Robbie Gould (Max Cantor), a young waiter who is currently courting Baby’s sister Lisa (Jane Brucker). Although extremely wealthy and handsome, Robbie is manipulative and selfish. When Baby confronts him and asks for money to pay for the abortion, he denies paternity and implies that Penny is promiscuous, which is another example of the condemnation of class distinctions in the film. Penny explains that she believed that Robbie loved her, and that she was “something special.” A woman who has no family, no real career prospects and is constantly belittled by her employers can quite believably become seduced by someone like Robbie. The film thus makes an important point about culpability – the poor, lonely and insecure Penny must bear all the blame and responsibility for the pregnancy, while the fortunate Robbie gets off scott-free.

|

| Patrick Swayze and Cynthia Rhodes |

Another important analysis of class distinction occurs in the film when the financial consequences of a back-alley abortion are discussed. Not only can neither Penny, Johnny nor Billy afford to pay for the abortion, Penny can’t take the day off to visit the abortionist. The abortionist is only in the area on one particular day, but Penny and Johnny are scheduled to perform at another hotel. There is no one who can take her place. Baby, established as a bit of an altruist, not only gets the money from her wealthy doctor father, but volunteers to learn Penny’s routine so she can get the procedure done. All three resort employees are shocked and guilty about accepting Baby’s kindness, as they are used to wealthy people exploiting them and treating them as sub-human. The romance plot is kicked off as Baby rehearses the routine with Johnny.

Unfortunately, the most frightening hazard of illegal abortion is that those who perform back-alley abortions are not certified doctors, and are under no regulations to use sterile equipment, anesthesia, or to perform the procedure safely. Outlawing abortion does not prevent abortions in any way – as we see in this film, if the woman is desperate enough, she will end the pregnancy regardless of the legal implications. Penny is thus locked in a room with an abortionist with a folding table and a “dirty knife.” Billy tries to come to her aid, but she is at the mercy of the abortionist and he must endure her screams of pain. Billy brings her home, and Penny refuses the help of a hospital as they would call the police. She is obviously dying, and is moaning in pain and clutching her abdomen. Baby goes to find her father, who is skilled enough to not only save Penny’s life, but also tells her that she can still have children. Her relief and joy at this news is an important aspect of her character, as it shows that this abortion was done because it was not the right time in her life to have a child, and that she had no choice in the matter. It is implied that someday, when Penny’s dancing career is over, she will have children when she is ready.

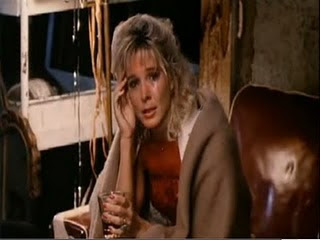

|

| Penny in bed, following her abortion |

Baby’s father, Dr. Houseman, seems to have conflicted morals, and serves a good example of someone who may not approve of abortion, but still shows compassion for women who require the procedure. He tells Baby that he doesn’t want her associating with “those people” (referring to Penny and Johnny) again, showing a protective streak and indirectly comparing the virginal and wealthy Baby to the poor “bad girl” Penny. However, when treating Penny’s condition, he speaks to her kindly, continues to make checkups on her despite his being on vacation, and happily converses with her at the finale. So despite his obvious disapproval of Penny’s choices, he sees her as a patient first, and makes her recovery his primary concern.

The purpose of legalized abortion is not only to give women like Penny a choice, but also to ensure their safety. It is very telling that class distinctions still exist (and are perhaps stronger than ever) in that wealthy lawmakers continue to blame perceived promiscuity for unintended pregnancies, and wish to force women to bear children as a punishment or consequence for their actions. If Penny had continued this pregnancy, she would have had absolutely no way to care for the child. She may have made a mistake in sleeping with Robbie, but why should she be “punished” and he not? Most importantly, keeping abortion legal and fully accessible saves the life of the mother. There are enough restrictions on abortion already – the doctors are only available on certain days in certain areas, some states require the woman to wait an extra 24 hours just to make sure they’re “certain” (Hint: They wouldn’t be there if they weren’t sure.), abortions are expensive, etc. Women like Penny should not have to risk their lives in order to ensure that they have control over their lives and their bodies. Before abortion was legalized in the US and Canada, women often died from the procedure. Women will get abortions whether or not they’re legal, because sometimes they have no other choice. I am sure I am preaching to the choir when I speak of the lessons I have learned from Penny’s story in Dirty Dancing, but part of me wonders if there would be more support for keeping abortion legal and accessible if lawmakers showed a little compassion, watched this film again, and thought about the real women whose lives mirror Penny’s.

———-

Myrna Waldron is a 25-year-old pop culture buff who loves to let off a good rant. She regularly tweets at @SoapboxingGeek, and is going to pretend the upcoming Dirty Dancing remake doesn’t exist.