A Conversation Between Max Thornton & Amanda Rodriguez

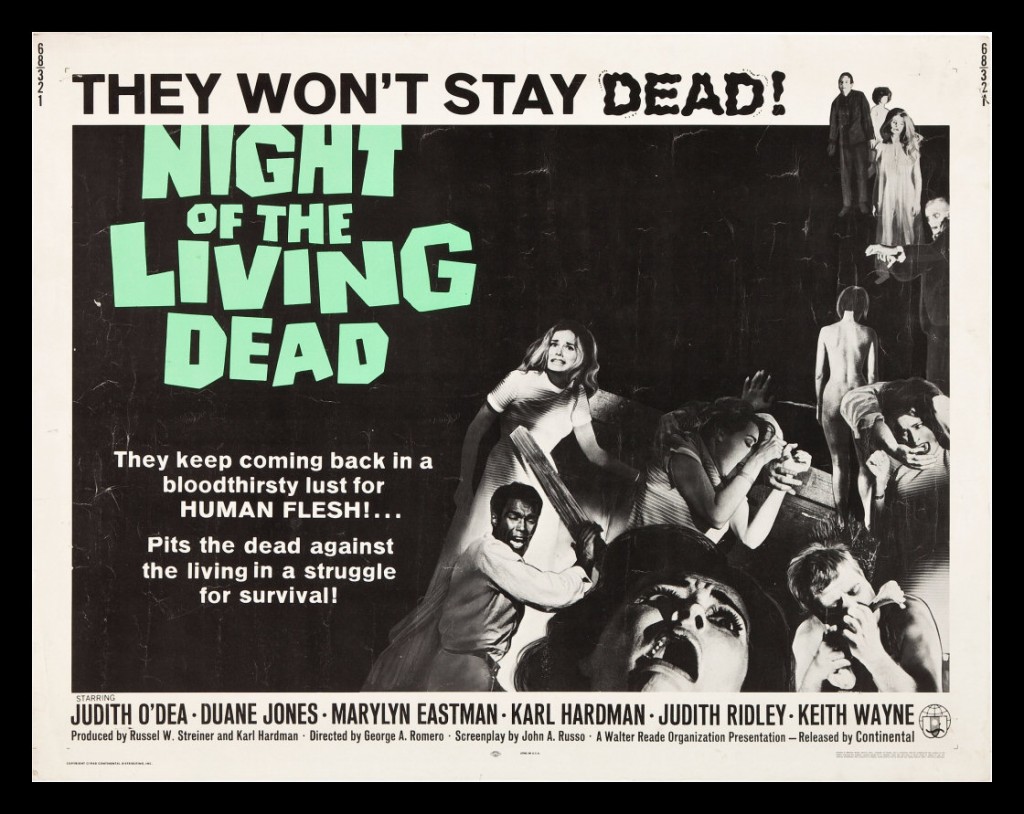

Birth of the Living Dead is Rob Kuhns’ documentary of the making of George Romero’s 1968 cult horror genre game-changer Night of the Living Dead.

[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TowiviD3xgE”]

Bitch Flicks writers Max Thornton and Amanda Rodriguez discuss both the documentary (BOTLD) and the original film itself (NOTLD):

MT: I spent my teens as an ardent fan of all things zombie (and I have a lot of theories about what this says about my relationship to embodiment as a trans person, but that’s another discussion). I went on a zombie walk in London for the 40th anniversary of NOTLD in 2008. I skipped a college class to go meet George Romero when he was doing a signing for the Creepshow re-release. My first academic publication is a chapter on zombies (and queerness, and Jesus, because those are my other favorite things). My cred as a Romero fan is well established, and I’m guessing yours is, too. Do you think someone who’s less of a zombie nut — or perhaps even someone who hasn’t seen NOTLD — could enjoy Birth of the Living Dead?

AR: I am a huge horror and zombie fan, but I didn’t start out life that way. I saw NOTLD when I was 4. I can empathize with Ebert’s observations of the younger children who didn’t have the resources to protect themselves from the fear and dread engendered by the film. I refused to watch NOTLD again until I’d graduated college because it was so formative and so terrifying. Perhaps in large part because of NOTLD, I have always been fascinated with what frightens us and why. The deep psychology of fear and what that fear represents within a larger cultural context have been the subjects of much of my critical analysis and fiction writing. I love the idea that horror, in particular the zombie, is a physical manifestation of our societal fears.

That said, I’ve only properly seen NOTLD once, so I think the documentary can be interesting to people who aren’t as entrenched in zombie culture; although who isn’t these days, considering they’re such a popular horror subgenre? I found Romero’s continued enthusiasm for the film all these years later to be quite endearing. Film nerds and aspiring indie filmmakers could find value in this documentary. People interested in history, particularly the civil rights movement and the Vietnam war could benefit from seeing this documentary, as it and NOTLD deal with those huge cultural landmarks from a different angle than we’re used to seeing. I also really appreciated the way the documentary casts NOTLD as a meta-narrative of the actual making of the film: the DIY approach and guerrilla tactics the crew used despite the huge filmmaking machine that is Hollywood. The process of making the film becomes its own protest against the Hollywood status quo, the insistence on professional actors, the elitism of art and entertainment. In a way, this is exactly the function of zombies; to disrupt the normalcy and complacency of institutions.

MT: Is this documentary perhaps a little too much of a hagiography? Does it give Romero too much credit for inventing the zombie as we know it, provide too little contextualization of the Haitian origins of the zombi, and thus perhaps whitewash the racism, colonialism, and cultural appropriation inherent in our cultural enthusiasm for the zombie?

AR: Though I thought Romero was a sweet man, and as a fan, I couldn’t help but gobble up his nostalgic reminiscences, the documentary underscored for me the importance of the concept of the death of the author and the fallacy of the notion of authorial intent. It is clear that Romero had no idea what he was making. This film is considered a cult classic and of cinematic significance in spite of him. He makes it clear that he didn’t intend to comment on race by casting a black protagonist, and I doubt he had any idea he was critiquing the Vietnam war or truly upsetting the horror genre in a profound way. I think the film does all those things in a compelling way, which is why it withstands the test of time and is infinitely imitable. Without divesting him of his agency completely, the documentary shows that film experts and filmmakers today understand the important work he created more than Romero himself does.

You’re right that the documentary seems to gloss over the true origins of the zombi, which does divorce it from its racially-charged roots. However, I always thought the movies that predate NOTLD featuring Haitian zombis were painfully racist. Romero zombies are different from the Haitian zombi and speak to our culture in a different way…probably because the Romero zombie is versatile and can morph into any of our greatest fears. It would have made sense, though, to have the documentary further explore the origins of the zombi. Since BOTLD is so racially aware, I would have enjoyed seeing it tackle the implications of colonialism and appropriation. Do you think Romero’s so-called reinvention of the zombi is ultimately racist? Does his malleable notion of zombies only address first-world fears and insecurities?

MT: I think this is something that deserves more interrogation than it tends to receive — consider the fact that he always cites I Am Legend as a huge influence, and not the Haitian voodoo roots or even the massively racist earlier zombie films like White Zombie — but then NOTLD doesn’t actually use the term “zombie.” As well as getting more credit than he deserves, perhaps Romero gets more flak than he deserves when we criticize his appropriation of the zombi, because, as you point out, he doesn’t necessarily know quite what he was doing. (I would note that some people are attempting to balance out the deification of Romero as inventor of the modern zombie: the editors of my zombie chapter, for example, were very insistent on giving Romero’s co-writer Russo equal credit.)

I really enjoyed the film’s emphasis on the social context of the late sixties and how that shaped much of the imagery and message of NOTLD: race riots, Nam, anger, disillusionment with the hippie movement’s failure to elicit major structural change. Are we currently in a comparable period of crisis and distrust in institutions, reflected in the renewed zombie boom of the past decade? And yet is the profound social consciousness of NOTLD largely missing from zombie stories today? For example, I rage-quit The Walking Dead at the end of Season One because it seemed to me so profoundly the white men’s story, with the female characters and characters of color remaining firmly secondary to the almighty White Man. I think maybe I find this particularly disappointing in zombie stories because I want more out of a genre rooted in a movie that was so far ahead of its time in its attitude toward race.

AR: I think zombies will always appeal to us because our society is a house of cards. Zombies remind us of a life without the comforts of technology, safety, and structure. The more complicated and reliant we become on institutions and corporations, the more relevant dystopian fantasies like zombies become because we are one global crisis away from that house of cards collapsing on us, leaving us weak, reeling, and unable to fend for ourselves.

I think zombie movies are being made left and right because they’re a hot item, but a zombie movie isn’t truly great unless the zombies are a compelling metaphor. The last zombie movie I remember adoring was 28 Days Later because it explored the terrifying fear of pandemics, the brutality of the military, and the rage that exists inside us, constantly questioning whether or not human nature is really as pure and good as we’re led to believe. Though Naomie Harris’ Selena was its secondary protagonist and her characterization falters at the end, she is a majorly badass, smart Black woman who kicks some serious keister with a machete. (However, I didn’t love the sequel 28 Weeks Later because I thought that was some misogynistic bullshit.)

I, too, have been struggling with the TV show version of The Walking Dead. I even wrote a Bitch Flicks article comparing the superior graphic novel series to the show. You’re totally right; the show is reactionary, racist, and sexist. It’s not doing much new or interesting with its post-apocalyptic material, which has vast potential to make meaningful commentary about what day-to-day life looks like when you’ve stripped our society away. There are questions ripe for the asking, such as: What do morals look like? How do you raise children? Can we work together against a common enemy (as touched on in the BOTLD), or are we inherently self-motivated?

What do you think the zombie trope “means”? Why do you think it’s still got such a stranglehold on us after over four decades?

Are zombies then not really a horror subgenre but a dystopian subgenre? Maybe the words “zombie” and “apocalypse” always go together. Can you think of any zombie film examples where the threat of utter human and societal annihilation were not issues?

MT: I wonder — and this is highly speculative, and clearly born out of my perspective as a theologian with seminarian friends who worry a lot about the decline of mainline Christianity in the US — if the zombie’s place as a monster of the 20th and 21st century is intertwined with secularism. Is it a manifestation of a certain cultural anxiety related to the “rise of the nones” — that is, a cathartic expression of a fear of being swallowed up by materialism (in both the philosophical and the economic senses of the term)? As mindless masses of rotting flesh whose only drives are the basest physical urges, zombies represent the logical extreme of pure materialism, and I suspect it’s not a coincidence that our cultural psyche is obsessed with them in a time when global capitalism is engulfing everything while traditional channels for religious/spiritual sensibilities are on the decline — among the young westerners who are the primary audience for zombie culture, at least.

It’s an odd and frustrating paradox that zombie stories are always these grand-scale, global apocalypses, and yet they always focus on your straight-white-male protagonists. This piece does a grand job of addressing this issue. I’d take World War Z as an example of the paradox: the book actually does take on the geopolitics of the zombie apocalypse on a truly global scale, whereas the film is a by-the-numbers Hollywood disaster flick where the global disaster is mere backdrop to the story of whiterocis dude hero and his perfect(ly passive) white family. I think that’s perhaps symptomatic of the increasing polarization of mainstream and independent content in our age of digital distribution, and I suspect that mainstream pop culture zombie tales are only going to get more anodyne and more unthinkingly supportive of the heteropatriarchal status quo, while we’ll have to look to non-traditional channels of production and distribution for interesting stories. I haven’t yet watched Ze, Zombie, a queer zombie film, but I’m deeply intrigued — not least, I admit, because the top update on the website is currently an apology for the film’s excessive whiteness…we’ve a long way still to go, it seems.

For all its social consciousness, though, does NOTLD (and BOTLD – only one of the talking heads is a woman; African-American men are interviewed, but African-American women are not) fall into the trap of so many progressive social movements, both in the sixties (e.g. black power) and still today (e.g. movement atheism): failure to properly include, address, and account for women? Do you know of any actually feminist zombie films (I can’t think of any)? Why is this such a cultural lacuna? Other movie monsters have been reinterpreted in explicitly feminist ways: vampires (Buffy the Vampire Slayer), werewolves (Ginger Snaps) — doesn’t the zombie have feminist potential as a movie monster?

AR: I’m totally with you on your critique of World War Z the film vs. the book. We’re like E.T. and Elliott here because I wrote a Bitch Flicks review critiquing the film: its narrative choices that narrowed the scope of the book until it was unrecognizable, the way it cast Gerry as a messianic figure, and its under-development of its potentially fierce female characters, rendering them as nothing more than symbols to reflect back upon Gerry’s manly manliness.

I’ve always thought that NOTLD wasn’t feminist when I consider all the female characters in the movie. I wish someone would have commented on the flat female NOTLD depictions in the documentary, but I guess the movie wouldn’t come out looking so well…the documentary does kind of lionize NOTLD.

I think Jennifer’s Body could maybe be categorized as a female zombie flick, but it’s debatable whether or not its feminist. Return of the Living Dead 3 was kind of a big deal because the protagonist was a woman and a zombie, and she became a sexual icon for teenage boys everywhere. I think part of the problem with associating zombies and women is that zombies aren’t usually sexy, and it seems like a requirement that women and sexuality are linked in cinema whether it’s in a feminist or a non-feminist way. So, I’d say that the lack of feminist zombie films speaks to a larger issue, in which our culture insists on associating women and sexuality.

There’s no real reason, however, why a woman can’t be the zombie killing heroine, though it happens so infrequently. We’ve got shitty examples like the Resident Evil series, but I think there’s a lot of potential to critique the patriarchy in a film that sets up a lone woman (or a small group of women) working against the never-ending onslaught, the plague of patriarchy. Wow, now I’m stoked to see that movie! Think it’ll ever get made?

Romero identifies as “Spanish” as per his Sharks vs. Jets anecdote in BOTLD, but he’s of Cuban & Lithuanian descent. He’s never represented as a director of color (I bet his last name, as he mentions, is often mistaken for Italian), and I wonder if that has an effect on the distribution and reception of his films? Would horror films directed by a POC known to have an underlying social and political commentary be shunned by the mainstream or turned into an even more exclusive niche (i.e. something like “politically-charged cult horror films by people of color”…ugh)? I also wonder if that’s why he’s well-known for casting characters of color in his films without sort of thinking about it: because he views race differently than, say, his white director counterparts?

MT: Your point about Romero and race is really interesting, and I hadn’t considered that before. The idea that he’s a POC who’s never read that way does go a long way to explain the use of race in his films. The history and theory of the “passing” POC is too often elided or overlooked in a lot of critical race discussions, and perhaps this element nuances the question of misappropriation of zombi above? It definitely merits more analysis!

And I think Romero’s engagement with both race and gender does get more explicit in his later films, notably Day of the Dead (clearly a heavy influence on 28 Days Later) and the very underrated Land of the Dead. It’s not an accident that Land‘s Big Daddy, the first zombie to develop a sense of consciousness, is African-American, and Land‘s whole narrative of class warfare is extremely relevant. (Now I kind of want to have future discussions about each of Dawn, Day, and Land of the Dead, looking at the evolution of Romero’s social consciousness over the years and films!)

AR: I’m in complete agreement about Romero’s evolution as a socially and politically conscious director in his later films. Dawn of the Dead‘s critique of consumerism is probably the reason that I insist upon socially relevant zombie interpretations. I also find it fascinating and a bit depressing that the 2004 Dawn of the Dead remake was lazy in that it eschewed the critical commentary inherent in a mall-based zombie flick, proving once again that we’re not necessarily getting better or more self-aware as a people. Romero’s Diary of the Dead I also thought was an interesting engagement on the notions of the viral connection of online media and the viral nature of information, despite its ultimate disappointment as a film. Although Land of the Dead wasn’t as commercially successful nor as engaging as some of Romero’s other films, I, too, was impressed by its class critique and some of its underlying racial commentary. However, I think the Black man emerging from the water with his new sense of self-awareness is a problematic depiction, putting Africans and African Americans on a slower time line for evolution than white people, claiming (perhaps unintentionally) that their consciousness is nascent, which is a disturbing paternalistic attitude.

This is one of my long-held issues with the horror, sci-fi, and fantasy genres. In order to tell these socially and politically charged stories, they embody the Other in monster flesh: think the apartheid conversation in District 9 with the grotesque alien bug people or Oz, the werewolf, along with Angel, the vampire, in Buffy and even more so in the Angel series or the way all the Star Trek series are rife with the creation of Othered alien species to elucidate the plight of an oppressed people (not to mention the racism inherent in the vicious warrior Klingons as stand-ins for Black people or the antisemitism of the greedy, urbane Ferengi as stand-ins for Jewish people). While the metaphor comes across, it often dehumanizes and further Others those it is attempting to bolster.

I could talk about this stuff for days and days! Count me in for future convos on the rest of the Romero zombie films! I’m planning to watch his Survival of the Dead, the last of Romero’s zombie series, for a Halloween-y treat since I’ve shockingly never seen it before.

—-

Thanks for joining us for this conversation between Max Thornton and Amanda Rodriguez on ‘Birth of the Living Dead’ and ‘Night of the Living Dead’. Keep an eye out for Max’s upcoming interview with Esther Cassidy, producer of ‘Birth of the Living Dead’.