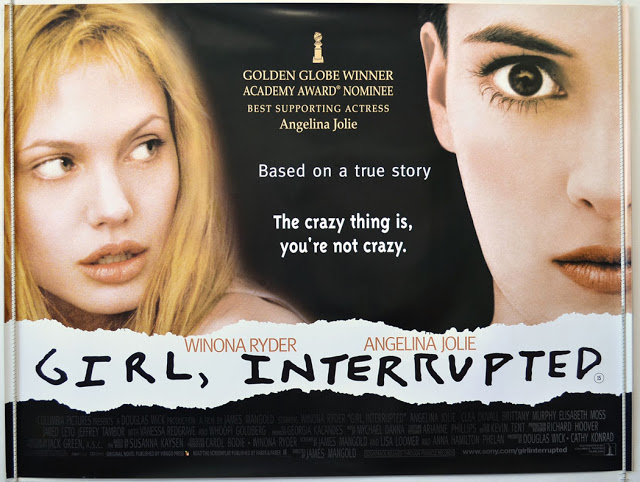

Father of the Bride (1991) is aptly named, as its focus is not on the wedding itself or the couple involved but on the titular character’s neuroses and journey to maturity. The wedding is the backdrop and the incident that provokes growth in the main character; it follows the wedding script

in toto, so if you’re unfamiliar with any of the conventions of a traditional US wedding, this movie is a great primer. It’s an outrageously expensive, white wedding for thin, wealthy, white folks. People of color and gay men exist as support staff and

magical queers. But the movie’s take on gender roles is constructive. Despite its focus on a male character, the movie is really about the affection a father feels for his daughter. He’s always recognized her as an individual person; now he must recognize her as an individual

adult person.

The plot is pretty predictable. Female subservience is challenged, but standards of female beauty aren’t. The characters aren’t remarkably complex, but their motives are clear and almost always understandable. That said, this is a romantic comedy. I don’t mean to demean the genre as a whole, but I think it’s safe to say most blockbuster romantic comedies are pretty damn problematic, so to have a romantic comedy that subverts the notion of valuing wives who are simply beautiful and submissive while featuring a predominantly black cast and depicting Africa positively, I’d say that’s a win.

And this is where the real problem comes in. We’re clearly supposed to feel bad for Jack’s plight and the DOMA-fueled injustice being heaped on him. But as things escalate and Jack suddenly falls for Spanish architect Mano (Maurice Compte), the casual viewer is more likely to feel bad for Ali, who has to deal with him gallivanting all over the place and not even trying to make their relationship seem remotely realistic. Her future is on the line right along with Jack’s, but Jack never seems to have an inkling of just how big of a risk they’re taking for his sake.

Weddings in the movies and in television always seem to be more elaborate than those we experience in reality. Fictional characters with traditionally low-paying jobs somehow find a way to have a wedding that would cost literally a million dollars in the real world. They’re often over-the-top with hundreds of guests, extravagant meals and elaborate ice sculptures–you know, fluff.

This is the second time I’ve seen Lizzy Caplan in her easy portrayal of the emotionally damaged wild child, the first being in Bachelorette where similarly, the wedding brings up all of her feelings about past relationships and a surprise pregnancy. It’s a character I like, one that while not original, is also not the most common of characters (similar to Natalie Portman in Friends With Benefits, Charlize Theron in Sweet November). But I like the character; it’s one where, rather than neurotic, and desperately searching for love and marriage, she’s the opposite–skittish and non-committal, frustrating and sexy.

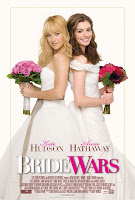

No, in Bride Wars that brand of madness is entirely female. This says nothing good or particularly realistic about the state of mind of the modern adult female. I mean, yes, we get hurt and pissed off when our friends do something that seems designed to cause pain to us, but how many of us who are not mentally ill follow them around, actively trying to ruin one of the most significant and expensive days of their lives?

Kristen Wiig’s character goes through the same kinds of ordeals we all go through—the kind that make us question who we are and what life is about. And her struggles are so frustrating and so moving that I found myself actually sobbing through the middle of the movie. The crazy thing about it is that while I was sobbing, I also started laughing. I’ve laughed and cried in a movie, but I’ve never before done both at the same time, and I did both while watching this movie more than once. I always tell my students that over-the-top comedy only works if it is paired with real, honest emotion, and my response proves that is something Bridesmaids does really well.

Fiona’s self-loathing over her ogre self goes extremely deep. When she confesses that she’s an ogre to Donkey, she says that no one would want to marry a beast like her. Shrek overhears this, and believes she’s talking about him. When he confronts her about it, and throws her words back in her face, she immediately assumes he’s talking about her. Fiona has overheard Shrek make comments about his identity as an ogre and the issues that come with it, so it wouldn’t be a huge leap for her to consider the possibility that Shrek overheard her and thought she was talking about him. But Fiona’s self loathing runs so deep that she doesn’t even consider the possibility.

Revisiting this film five years later (as a happily paired person once again), I find myself chafing against the film even as I enjoy the drama. The choices and mistakes that Carrie make from the time that she and Big decide to marry to the moment he leaves her at the altar about a third of the way through the story are the choices and mistakes that many modern American women make: ignore the man and his wishes, allow friends to convince you that you need a fancier dress, venue, event, and become more enamored with the grandeur and history of a luxurious location over the real fears and concerns your partner has about a large, intimidating, and ostentatious event.

To make matters more homophobic, in a move that makes absolutely no sense, George is press-ganged into playing the part of Julianne’s fiancé. It’s really gross to watch a gay man forced to play beard to a straight woman, shoved into a closet to suit her conniving privilege. Kimmy hyperventilates in relief that Julianne is apparently no longer her competition, because nothing promises a more stable marriage than making sure there are no hot women around to tempt your man. George gets his revenge by telling apocryphal stories about meeting Julianne in a mental institution where she was receiving shock therapy, because we might as well add mocking the mentally ill to this movie’s list of sins.

Leonato’s denunciation of Hero is the most disturbing moment of the film, as it should be. Verbal and physical abuse at the hand of a lover or boyfriend is traumatizing and life-altering, but there is something profoundly and uniquely painful in suffering at the hands of a parent. The casting of Clark Gregg, aka everyone’s favorite Agent Coulson from The Avengers, is a particularly brilliant move; any fan of Joss Whedon’s is conditioned to see Gregg as a good guy, and the moment of betrayal feels particularly pointed when coming from the mouth of such a likable actor.

So, is this a feminist film? Well, I think it highlights the significance of female friendship, but Carrie falling comatose when she’s jilted at the altar seems a bit much. While Carrie hires an assistant to organize her life, romantic love seems to be the ultimate goal. Meanwhile, Carrie bonds with the separated Miranda by telling her that she’s “not alone,” she reaches an understanding with the anti-marriage Samantha, and she celebrates Charlotte’s baby-bliss, even as she mourns her relationship, which has not actually ended. The film has its moments, and Carrie overcomes her obstacles without the direction or approval of any man. However, the film’s bigoted lines and treatment of Louise as a modern-day slave leave a bad taste in my mouth.

Even though I had fun with it, I have to say if you are engaged, you should probably limit your exposure to wedding movies. Because so many of them end with broken engagements or dramatic jiltings at the altar, you’ll start seeing potential wedding saboteurs in all your friends, family, and hired wedding professionals. You’ll see the obviously doomed engagements at the start of those movies and worry that if those characters could be so deluded, are you and your partner as well? You’ll think spending thousands of dollars renting chairs is ok because at least you didn’t invite random strangers from your mother’s past for an ABBA-scored paternity-off.

Muriel’s Wedding is basically a cautionary tale about valuing status and reputation over real connection. Muriel knows that she’s happy with Rhonda in Sydney, but by fulfilling her fantasies of beauty, wealth, and romantic achievement, she forgets her real strength: her honesty, decency, and kindness. These strengths were all there in her mother, Betty, whose cruel fate turns the movie from a girly romp into something much more meditative. She is talked over, pushed around, and utterly ignored, invisible even in her own home. Betty barely gets a moment of self-determination before she commits suicide, and her presence is felt most deeply in the frightening image of the Heslop backyard: a swath of literally scorched earth, where nothing can grow if nothing is tended and cared for.

There is one redeeming quality in this movie, and that is when Emma–who is a people pleaser for much of the movie–eventually starts to grow a backbone, while Liv–who is pushy and determined–softens up by the end. I’m hoping that the audience can take from these character shifts that women can be both determined and compassionate and that it is not disadvantageous to be both.

Jumping the Broom focuses on two strong customs — one being jumping the broom that has predated slavery, which Jason’s mother Pamela strongly supports, and saving sex for marriage. Sabrina and Jason obviously have strong physical desires for one another, but they’re willing to postpone physical intercourse and are continuing to know each other on various intimate levels — emotional primarily. This isn’t essentially common in most romantic films, especially an African American centric film.

Twenty years after Four Weddings and a Funeral, it strikes me that very little has changed. If this film were made today, Gareth and Matthew could enter into a formal civil partnership, but regardless, Charles may not have realized just how deep and committed their relationship had been all along. It’s still very bitter and chilling that it was the committed gay couple that was separated by death. The real theme of this film isn’t weddings and marriage, it’s commitment. Twenty years later, there’s still so little representation of disabled people in films. I honestly can’t think of another film I’ve seen with a deaf-mute character. There should have been more racial minorities in the cast, even in minor roles, instead of just one 5-second shot of a black extra at the funeral. And as comparatively progressive as this film is, all it does is make me think how ridiculous American films look. A film made in a country with a fraction of the US population is more representative of minorities than most films made in a country with 316 million goddamn people.

People who claim to believe films and TV and pop culture moments like this are somehow disconnected from perpetuating rape need to take a step back and really think about the message this sends. I refuse to accept that a person could watch this scene from an iconic John Hughes film—where, after a party, a drunk woman is literally passed around by two men and photographed—and not see the connection between the Steubenville rape—where, after a party, a woman was literally passed around by two men and photographed.

These posts about wedding films previously appeared at Bitch Flicks:

Movie Review: Rachel Getting Married by Stephanie Rogers

Rachel Getting Married: A Response by Amber Leab

Documentary Preview: Arusi Persian Wedding by Amber Leab

Review in Conversation: Sex and the City: The Movie by Stephanie Rogers and Amber Leab

Bachelorette Proves Bad People Can Make Great Characters by Robin Hitchcock

Feminism in Aiyyaa and Why It Ain’t Such a Bad Movie by Rhea Daniel

Realistic Depictions of Women and Female Friendship in Muriel’s Wedding by Libby White

Romantic Comedy (and Female Friendship) Arranged Marriage Style by Rachel Redfern

Movie Review: Something Borrowed by Megan Kearns

Movie Review: Melancholia by Olivia Bernal

The Five-Year Engagement: Exploration of Gender Roles & Lovable Actors Can’t Save Rom-Com’s Subtly Anti-Feminist Message by Megan Kearns

Bros Before Hoes, or How Kidnapping Makes for Great Dance Numbers: On Seven Brides for Seven Brothers by Jessica Freeman-Slade

Movie Review: Melancholia by Hannah Reck

Melissa McCarthy in Bridesmaids by Janyce Denise Glasper

“Love” Is “Actually” All Around Us (and Other Not-So-Deep Sentiments) by Lady T

Everything You Need to Know About Space: 10 Reasons to Watch (and Love!) Imagine Me & You by Marcia Herring

The Reception of Corpse Bride by Myrna Waldron

Movie Review: Room In Rome by Djelloul Marbrook

Movie Review: 500 Days of Summer by Stephanie Rogers

(95) Minutes of Pure Torture: 500 Days of Summer by Deborah Nadler

Gay Rights and Gay Times: Gender Commentary in Husbands by Rachel Redfern

Bridesmaids: Brunch, Brazilian Food, Baking, and Best Friends by Laura A. Shamas