|

| The Great Lie (1941) |

My mother used to sit me down to watch movies in front of a small black-and-white TV in our Southern California living room, not far from Hollywood, where she’d spent the happiest years of her childhood. Watching movies was part of a wide-ranging curriculum of aesthetic exercises she assigned my brothers and me. Not just any movie. The classics from MGM, the comedies from Paramount, an occasional noir from Warners. I’ve never been able to simply watch a movie like a normal person. I’m always evaluating the design elements, the performances, the script.

|

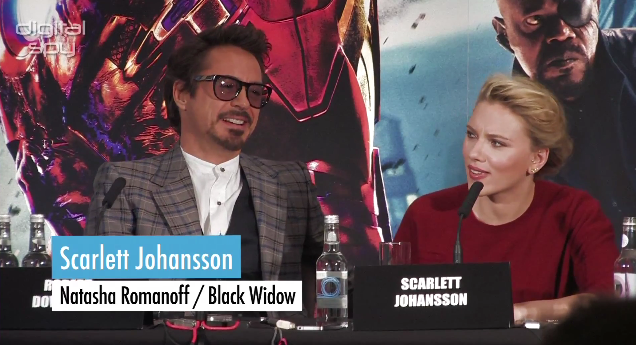

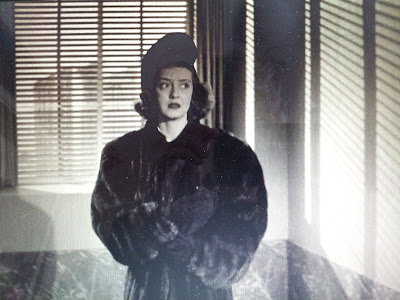

| Bette Davis stars in The Great Lie |

In 1941, when my mother was 17, the United States entered World War II and Warner Brothers released The Great Lie, starring Bette Davis and George Brent. Bette Davis was a great actress and George Brent was the only actor in Hollywood who hadn’t gone away to war. Unthinkable today that an actor would put his high-priced face in harm’s way but in 1941, the U.S. did not have a standing army, or a “volunteer” army of mercenaries, let alone private contractors. What was called “the war effort” included the publicity generated by the donning of uniforms by Hollywood stars, several of whom saw active duty.

There are two scenes in The Great Lie that made an indelible impression on my teenage psyche. One involves crossdressing, the other involves food, and both express the anxiety attached to giving birth and the difficulties modern women have integrating this biological imperative into an otherwise blithely artificial lifestyle. But mostly, these two scenes depict powerful moments of emotional intimacy between women in which conventional gender roles go out the window.

The Great Lie, despite its portentous title, was not part of the war effort, although George Brent’s character, Pete, dons a uniform right after his wedding and flies off on a secret mission to a South American jungle. Pete’s lackluster presence at movie’s start and extended absence during movie’s middle is characteristic of what was called “women’s films,” in which the man is merely a rag doll to be fought over by the real characters: female rivals who vie to possess him.

|

| Mary Astor plays Sandra |

Mary Astor, whose name is one-third the size of George Brent’s (whose name is one-third the size of Bette Davis’s — whose name is alone above the title) on the original poster, is the pivot point of this romantic triangle. She’s better known for playing Brigid O’Shaughnessey opposite Humphrey Bogart in The Maltese Falcon, a truly great film released the same year. Astor’s particular cocktail of beauty, eroticism, class, emotivity, intelligence, weakness, and the febrile glamour synonymous with mental instability raise The Great Lie to the level of… what exactly? Something more exciting than it deserves to be, something operatic with the frisson of a tabloid. She won an Oscar for her performance.

Astor plays Sandra, the internationally acclaimed concert pianist, whose manager (Grant Mitchell) refers to her as Madame Kovac. Unthinkable today that a concert pianist could feature as a love interest in a Hollywood film but in the 40s, classical music was part of the national dialogue and every kid in Brooklyn was trying to get to Carnegie Hall. Astor is believable as a concert artist, although the script by Leonore Coffee (revised on set by Davis and Astor) trades in clichés about the artist’s life. No matter. Astor brings an innate musicality to her scenes. Her voice, a rich contralto, is itself a stunning instrument.

The opening credits roll over a series of tightly framed shots of a woman’s arms banging out Tchaikowsky’s Piano Concerto Number One on a Baldwin, backed by a healthy string section. The piano is muscular, the ascending chords weighty, rhythmic, obsessive. The whole sequence establishes the beating heart of passion which is the source of the great lie. (Those aren’t Astor’s arms, but we do get some choice glimpses of her banging away at the keyboard. She brings to it the conviction of a trained pianist.)

The production values in this film, dynamically directed by Edmund Goulding, are uniformly excellent, from the supporting cast, to the sets, props, costumes and the kind of chiaroscuro lighting you only get from Warner’s. Watching it for the umpteenth time, I was struck by the pacing, how the camera patiently tracks the actors. This approach is futile when filming George Brent, who has little to give, but pays off with Mary Astor, who has the reactivity of uranium. And, of course, Davis knows exactly what to feed the camera at all times. Starting with her famous eyes.

|

| Maggie and Pete post-wedding |

Exhibiting those characteristics considered essential to the life of a temperamental musician, Sandra marries Pete while they’re both on a drunken spree, but the marriage is annulled post-consummation when it’s revealed Sandra’s divorce from her previous husband wasn’t yet final. That frees a newly sober Pete to rush back into the arms of Maggie (Davis), his true love. They marry without delay but the rivalry continues when Sandra discovers she’s pregnant. The fetus is considered a powerful bargaining chip in her attempt to recapture her runaway husband.

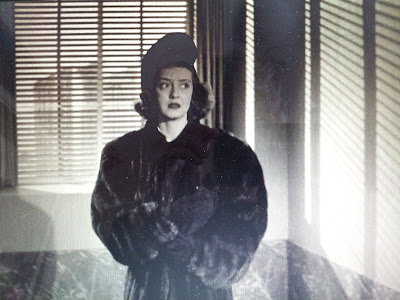

When Pete’s plane’s reported missing somewhere in the South American jungle, the great lie is concocted in the head of his wife Maggie, who sees a way to preserve Pete’s only known earthly remains — his DNA — by getting his ex-wife to carry his child to term. In a stunning surrogate switcheroo, it’s not the paternity but the maternity that’s going to be in question. Maggie shows up at Sandra’s Central Park apartment in full noir regalia: wide-body fur coat and oversized black hat. Sandra’s in haute bohemian chic: a stunning floorlength black dressing-gown.

|

| Maggie arrives at Sandra’s apartment in suddenly-noir lighting |

Sandra leans back on her white satin bed, cowed by the interloper’s assertiveness. Maggie stands looking down at her and explains, “He left us two things in this world. I have his money. You might have his child. You’re extravagant. You’re a woman of the world, a public figure. Your piano, your success, they won’t go on forever. None of us gets younger. Let me insure your future. And you ensure mine.”

Sandra asks, “Your future?” Maggie says, “His child. That could be my future. And I’d make you secure financially always.” Sandra considers this, then says softly, “Money.” Maggie says, “Yes.” Sandra shakes her head dismissively. “It’s so completely mad.” Exactly what the audience is thinking.

Fifty minutes in, we’re at the heart of the matter: an extended showdown between virtuous wife Maggie and vicious baby mama Sandra. Implicit to the great lie is the thwarting of an abortion but that precise issue is never raised. This kid’s life only has meaning as an extension of Pete’s. That’s the one thing these two women can agree on. They love that man!

|

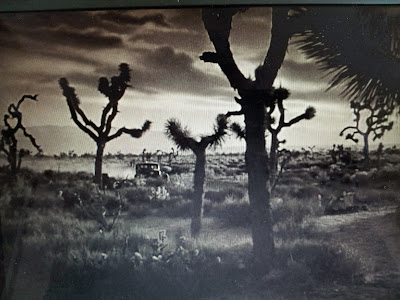

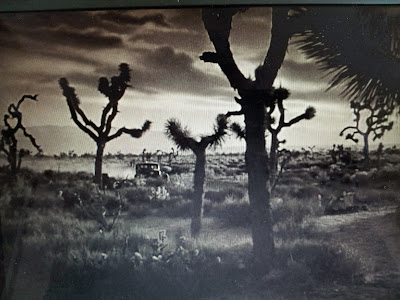

| Their car arriving at the Arizona safe house |

This scene kicks off twenty minutes of high histrionic and low comedic bliss as Bette convinces Sandra to hide out in a clapboard house in the Arizona desert, surrounded by dust and cactus, serviced by an untraveled road. Scenes of delicious intimacy suddenly erupt as the actresses sink their teeth into their new roles-within-roles. None of this would work with lesser actresses playing for laughs or, worse, camp. There’s a same-sex erotic undercurrent a mile wide to these domestic scenes, under a thin frosting of glamour puss personality. Astor unleashes a volatile vulnerability which Davis parries with pugnacious charm. And I’m suddenly reminded of a similar set-up in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), where Bette Davis dominates the wheelchair-bound Joan Crawford. That’s the late-career, Grand Guignol version.

Maggie deploys wifely know-how to tend the tempestuous Sandra, grown crankier in a terrycloth bathrobe through forced isolation, dietary restrictions, and the gratingly upbeat companionship of her arch rival. But is Maggie the wife or the husband? She runs errands for Sandra in town. She monitors her cigarette smoking, unsuccessfully. She even keeps her from eating a pickle during a middle-of-the-night fridge raid. This scene is unique in the canon, for the pathetic self-abasement Astor offers up in her quest for a ham sandwich.

|

| Maggie relents and cuts a slice of ham for Sandra |

Awakened by a wind storm, Maggie’s attracted by the light under the door to the kitchen. She enters and finds Sandra, frozen in dread, like a mouse cornered by a cat. Maggie gestures to the table full of food. “Sandra. Ham, onion, butter. Everything the doctor said you couldn’t have. What have you got behind your back? Come on. Hand it over.” Sandra puts a jar on the table. “Pickles. Oh, Sandra.” Sandra answers, “Yes, pickles. I like them. I want them. I’m sick and tired of doing without things I want. You and that doctor with your crazy ideas of what I can and what I can’t eat. You’re starving me.” The martyred Sandra practically sings her lines. “I’m not one of you anemic creatures who can get nourishment from a lettuce leaf. I’m a musician. I’m an artist. I have zest and appetite and I like food. I’ve being lying awake in there thinking about food and now I’m going to have it.” So Maggie gives in and makes her a sandwich.

|

| Maggie alone on the deck, awaiting the birth of the baby |

The greatest transgressive thrill comes when the country doctor arrives to deliver the baby. Maggie’s prowling around in men’s slacks and loafers, odd man out at this female ritual. When the doctor says he’s used to having the father around, nervously wondering when the baby’ll be born, he’s describing Maggie. Then he closes the door to the bedroom, shutting her out of this women’s mystery. Virile Maggie can’t sit still but goes out onto the deck, alone in the night, smoking and pacing like a guy until that universal signal, a baby’s cry, summons her back inside. Women, too, can be fathers! She enters the bedroom only long enough to eyeball Junior. This baby is an abstract goal for Maggie and Davis is not a convincing mom.

|

| Sandra playing Chopin, dressed to impress |

I don’t think it’ll spoil the movie for you to reveal that Pete is not dead and that his resurrection as a plot point reignites the women’s rivalry. The Great Lie is nothing if not a primer in how to get melodramatic mileage out of a baby. That’s when Pete surprises us all by declaring that he prefers a childless Maggie to a babied-up Sandra. Like the judgement of Solomon, this remark reveals the identity of the “true” mother, Maggie, who, while not the biological parent, is the one who wants to keep the kid. To cover her humiliation, Sandra sits down at the baby grand and starts banging out the same concerto we heard under the opening titles. We’re back where we started.

|

| Violet (Hattie McDaniel) leads the celebration |

The one big glaring no-no smack in the middle of The Great Lie is Hattie McDaniel’s reprise of her role of Mammy from Gone With the Wind (1939). They’ve changed her name to Violet, but her function is the same. Treating Maggie the way she treated Scarlett O’Hara (a role Davis famously fought for and lost to Vivienne Leigh) only makes sense within a regressive, racist fantasy. It’s mind-boggling to watch the scenes of happy blacks celebrating their mistress’s wedding. Did anything remotely resembling that world exist in 1941? Because it sure doesn’t exist now. But then, The Great Lie is a time capsule full of outmoded conventions. Which is what makes it so fascinating.

Erin Blackwell reviewed films for the Bay Area Reporter

in San Francisco. She just finished writing a play. Her blog is Pinkrush.com.