This is a guest post by Margaret Howie.

With the release of

Taken 2, Liam Neeson impersonations are all over the internet again. You’d think that we had all been starved of Neeson material, but it was only back in January that his Man vs. the Wild movie,

The Grey was released. Along with it we got a PR campaign based largely around his qualities as a leading man, and some revealing media coverage about gender roles in cinema.

The trailer for The Grey ticked all the familiar wilderness survival story clichés, right up until one of the last shots. That was the sight of Neeson taping broken bottles to his fists for a head-on confrontation with a pack of wolves. Accompanying this enticing promise of Neeson taking on predators fist-first, the surrounding promotion promised even more from the movie.

The Grey was going to be more than an action flick. It would be a profound examination of the state of modern man. Much of this argument centred on the casting of the Northern Irish actor, and the director’s insistence that his star represented something lacking from modern film: authentic masculinity. Eventually much of the discussion of

The Grey turned into rants about maleness. It shows how depressingly quickly gender stereotypes can be recycled and reinforced in something as innocuous as movie promotion.

|

| Liam Neeson in The Grey (2012). Beard. Check. Snow. Check. Y Chromosome. Check. |

Post-

Star Wars, Neeson has become best known for his display of clenched-jaw determination in the face of cinematic adversary. Almost twenty years since

Schindler’s List, the audience has faith in his capabilities to release the Kraken, defeat terrorists, get his daughter back and punch out a wolf. Parodies of his line deliveries in 2008’s

Taken and 2010’s

Clash of the Titans continue to get uploaded to YouTube. With the release of

The Grey there was another opportunity to salute his hard-boiled, reluctant-action-hero persona and reflect on how it fits in a survival film.

Directed by Joe Carnahan and co-starring Frank Grillo and Dermot Mulroney,

The Grey is described by

Open Road Films as the story of “an unruly group of oil-rig roughnecks when their plane crashes into the remote Alaskan wilderness. Battling mortal injuries and merciless weather, the survivors have only a few days to escape the icy elements – and a vicious pack of rogue wolves on the hunt.”

What goes without saying is that the group is all-male. What did go on to get said, across film blogs and in news reports, was that the men of this film were delivering something supposedly missing from the cultural diet. Gender quickly became one of the most-discussed themes of

The Grey’s pre-release coverage. Both movie reporters and their interviewees worked lines about masculinity into the discussions. Soon an idea of Liam Neeson’s ‘maleness’ being some sort of scarce resource emerged. The subject was set up by Neeson’s particular popular culture position, the mostly male cast, the genre and the writer/director Carnahan’s strident views of the state of casting in Hollywood. Is there really a dearth of manliness in cinema? Or does Dermot Mulroney get it right when

he complained that “all the f–king movies are about the girls”?

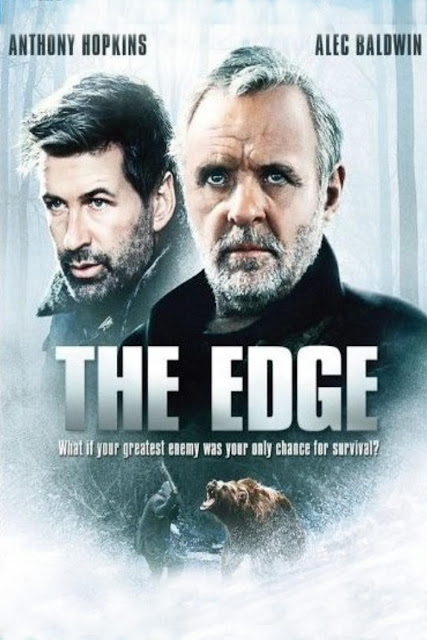

The wilderness survival movie tends to be a generically male construction. In December 2011,

Collider reviewed the trailer and Matt Goldberg added, “I can’t remember the last time we saw a solid men-vs-wild movie [since

The Edge].” But perhaps the title should have reminded him. Men vs. wild films have been coming out solidly, even if you only count ones with ‘The’ in the title. Since

The Edge was released in 1997,

The Hunted,

The Missing,

The Way Back, and

The Donner Party have all provided stories of steely-eyed male protagonists facing down both the wilderness and the worst of human nature.

|

| Alec Baldwin and Anthony Hopkins in The Edge. Beards. Snow. Wilderness. Etc. |

In a ‘close read’ of the film, posted on the day of the film’s release,

Movieline’s Jen Yamato asked whether

The Grey was a “

welcome return to masculine cinema.” This was explored through quotes from the cast and director. Actor Dermot Mulroney said, “I’ve made a lot of movies that had both men and women in them, a lot of movies that were dominated by the woman’s storyline. And in this case it was a very different experience making the movie and enjoying the movie, when it was completed, because of the fact that there are no women in it… It was like thank God, I get to do a movie with just guys.”

Cast member Frank Grillo said that “It’s tough being a man. It really is tough being a man.” His co-star Dallas Roberts was quoted as saying, “But that’s the problem with discussing modern masculinity, isn’t it, because you’re a moron as soon as you open your mouth and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Mulroney expanded on the subject of cinematic testosterone in another interview with

Movieline. It went on to be posted under the headline “

The Sweet Relief of Being in a Manly Movie Like The Grey.” His response to a question about representing ‘what it means to be a man’ in the film was:

“So you say this movie has some throwback qualities, or some old school manly-man qualities; that’s intentional… So, guilty as charged on that; if that’s something that needs to be brought back, then let’s bring it back. It seems like people are responding to that about this movie and to my mind there haven’t been enough of them. The pendulum swung the other way since I started in this business and there were men’s movies like whatever those Tom Cruise movies [were]”

He continues “…then all of a sudden Sigourney Weaver comes in the Alien and we have strong women, we have Working Girl, we have all this, we have Best Friend’s Wedding, and before you know it, all the f–king movies are about the girls!”

Movieline’s headline presents

The Grey as a ‘sweet relief’ to this abundance of girls, uncritically accepting Mulroney’s point and working it in to the appeal of the movie for audiences. This theme of the ‘masculine’ film continued to crop up in the promotional work surrounding the film’s release. Carnahan went on to frame his casting decisions around an idea of endangered manliness. The

HuffPo blog

Tribeca Film highlighted it in their interview with him, using the headline “

Call of the Wild: Masculinity and Mother Nature in The Grey.” In the article, Carnahan talks about his cast, saying “They are unmistakably masculine as opposed to these vacuous kids in Hollywood right now…For

The Grey, I was interested in a very specific kind of masculinity.”

He goes on to summon up this ‘very specific kind’ as embodied by Neeson through comparing him with Justin Bieber. Carnahan positions manliness in terms of dismissal and revulsion with the kind of ‘vacuous kids’ teenage Bieber apparently represents, and links credibility with age. The casting issue comes up again in

The Daily Blam, where the writer Pietro Filipponi paraphrases his interview with Carnahan by saying “Casting…wasn’t as easy as you’d think” and quoting the director holding forth again on the seeming epidemic of “shirtless boys…with blank stares.” Filipponi suggests that “movie goers may scratch their collective heads wondering why other well known (and younger) actors weren’t selected for this film.”

In the

Film School Rejects interview with Carnahan they discusses the “surprise” fact that younger actor Bradley Cooper (who is 37) was “almost” cast, and the interviewer Jack Giroux also brings up the idea that Carnahan’s “characters are usually very manly.”

The connection between Neeson’s casting (the director calls it the film’s “trump card”) and the “manly” aspect of his character is presented as a given. The contrast between younger Cooper and Neeson, who is 59, isn’t pressed, but in another

interview with Moviehole the director continues to strongly connect his leading man with idealised masculinity. He says that “Liam embodied that much more easily than a younger actor would have” and commented on Neeson’s “strength and profundity as a man and as an actor.”

Discussions about

The Grey and its portrayal of endangered masculinity originated in the movie blogosphere, but proved to be popular beyond it. When Joe Carnahan told film site

Collider that Hollywood “premium on boys instead of men” and that films were “sorely lacking” in Neeson’s “ilk,” his quote was picked up by an entertainment news agency. The line came from a video interview with the director, who had been asked about the decision to cast his leading man. Talking about how “shirtless seventeen-year-olds” are being “passed off as a masculine form,” he goes on to say: “The reason that a guy like Liam, who’s nearly 60 years old, is having this resurgent kind of career swing is because we are sorely lacking in his ilk in this business right now.”

It garnered a decent amount of coverage, certainly more than most non-Tarantino director’s interviews are likely to, even in Oscar season. The quote was picked up by entertainment news agency

Cover Media and was recycled on entertainment sites like

ONTD and the UK’s

Daily Express. Along with the jokes made about Neeson’s wolf-punching virility it became one of the underpinnings of

The Grey’s online media coverage.

Magazine website

Crushable reposted Carnahan’s quote under the headline “

Liam Neeson Is Having a Career Resurgence Because He’s the Most Masculine Actor in Hollywood,” with writer Natalie Zutter concluding: “There are no men in Hollywood.” The same site emphasises Neeson’s skill set by creating a very manly

paper doll of him in full action hero pose. He’s pictured surrounded by everyday items he can recycle into “the perfect weapons.” Same as, the writer points out, Matt Damon in

The Bourne Identity – an actor and role not mentioned in her other article, probably because it dismantles the point that Zutter (and Carnahan himself) is making.

|

| Matt Damon in The Bourne Identity. Non-existent leading man. |

Yahoo’s

Shine blog used the line as a springboard to ask “

Where Are Hollywood’s Manly Men?” Author Piper Weiss reiterates Carnahan’s idea of a “lack,” referring to Neeson as the “last of the man-hicans” and calling them “a dying breed if ever there was one.” Weiss goes on to list ten other prominent movie stars who fit this particular “breed.” It harks back to Carnahan’s stated desire for a “very different kind of masculinity,” a call for an essentialist gender role of some type that’s now, apparently, unfashionable and endangered. Ironically, eight of them are white, unintentionally reflecting one of the true shortages in Hollywood casting.

Writer Christian Toto, writing for the conservative Breitbart’s

Big Hollywood blog, used Neeson’s profile to write about “

Why Masculinity Matters.” Comparing the profit of

The Grey with Taylor Lautner-starring action film

Abduction, Toto concludes that “the soon to be 60-year-old Neeson matters because he’s bringing something fresh to theatres, the sense of a fully capable alpha male who doesn’t regret taking decisive action.” How rare this ‘fully capable alpha male’ quality is, and how unique it makes Neeson’s appearance on screen, may appear inarguable when contrasted with the twenty-year-old Lautner’s box office disappointment.

However, Abduction opened up against two arguably manly films, Killer Elite and Moneyball, and only a couple of weeks away from several other testosterone-heavy storylines, Warrior, Drive, Courageous, and Real Steel. All of them featured flawed male leads, many of them (including Jason Statham, Clive Owen, Brad Pitt, and Hugh Jackman) old enough to be Lautner’s father. It also doesn’t take into account that Lautner’s film was beaten at the box office by a movie with negligible alpha-male qualities called Dolphin Tale.

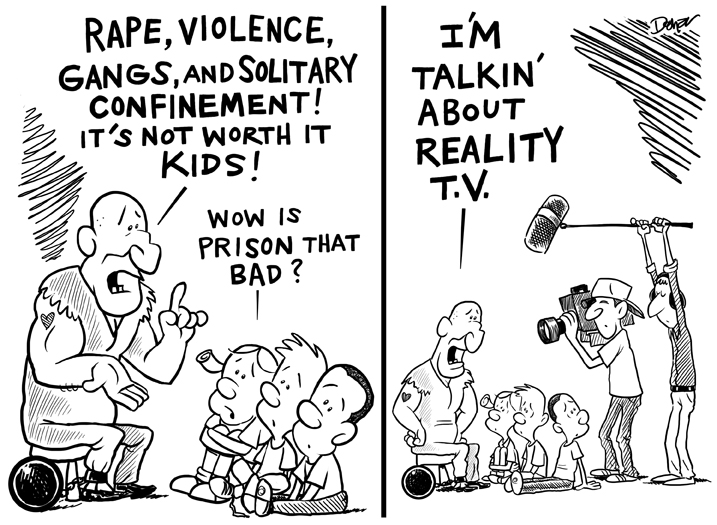

Masculinity definitely does still matter, as the

Women’s Media Centre study of gender representation [pdf] in U.S. media shows. It reported the distressing results of a 2012 report by Smith, Choueti & Gall on female representation in mainstream movies. The authors found that female characters made up just a third of the speaking roles in the top hundred grossing films of 2007, 2008, and 2009. Looking at ‘gender balance’ in these movies, where “the girls” contributed to around half of the characters, only one in six films qualified. In films, female leads are still the exception, never the rule, no matter how overwhelmed Dermot Mulroney feels.

Given this, it feels like an overstatement to hear all these announcements that cinema audiences will be shocked at seeing a cast of legal male adults, or even a star – Neeson – old enough to have fathered Bradley Cooper. Particularly considering that a writer who asked where the manly men are in Hollywood could then come up with ten prominent actors, like Daniel Craig and Harrison Ford, who fit her misty-eyed description of manliness.

The popularity of Carnahan’s quote shows off the attraction of discussing a non-event like ‘disappearing masculinity.’ This argument makes out that The Grey is a special event, a chance for grown-ups – particularly men – to have a rare opportunity to see themselves onscreen. As well as being savvy PR, there’s almost an ideological challenge in this. The lurking subtextual suggestion is that if the audience does not front up, there will be less and less of the kind of gender ideal that Neeson has come to embody, with his daughter-rescuing, wolf-punching cragged good looks and air of tragic fortitude. Man vs. wolf is also man vs. box office, man vs. the empty calories of what Carnahan dismisses as “shirtless boys with…blank stares,” and by extension a dearth of movies with ‘male’ stories.

Comparing like-with-like, North American January cinema releases have in fact offered audiences plenty of films with central adult male leads facing difficult odds. The Grey was being released on the same weekend as the expanded release of 50-year-old George Clooney in The Descendents, and in a month with new films starring Dennis Quaid, Mark Wahlberg, Ralph Fiennes, and Ewan McGregor, all actors over forty. In January 2011, The Way Back was released, about seven men and one young woman walking 4000 miles to escape the Soviet gulags. In 2010 came the general American release of the Alp-climbing adventure film North Face. In 2009, instead of a survival epic there was Taken, the terrorist thriller that marked the beginning of the recreated Liam Neeson as action hero. In 2008 the most recent Rambo film came out, bringing back the renegade army vet to fight the Burmese military junta in the jungle. In 2007 Joe Carnahan’s mostly-male action film, Smokin’ Aces, was released – as was kidnapping thriller Alpha Dog, a suitable name for a movie where six of the seven top-billed actors were male. The year before that, January audiences were given the option of going to see Eight Below, another survival tale set in the Antarctic, starring two men and their pack of dogs.

Men dominate the blockbuster field, and the cult of youth is not as entrenched as Carnahan makes out. Johnny Depp, Robert Downey Jr., Vin Diesel, Matt Damon, Nicholas Cage, and Will Smith all opened films among the top-grossing of 2011, and are all also on the far side of forty. Harrison Ford is over sixty, as is Sylvester Stallone, and soon movie theatres will see the return of Arnold Schwarzengger, born in 1947.

|

| Willem Defoe in The Hunter. Beard. Snow. Raw masculinity. Rinse and repeat. |

In 2012, while

The Grey opened in theatres, a trailer for the new film

The Hunter was released online. Instead of Man vs. wolf, this ‘The’ movie (starring 56-year-old Willem Defoe) is about Man vs. tiger. Linda Ge, writing for the comic book website

Bleeding Cool, compared it to

The Grey, adding that the Neeson film may be “paving the way for moviegoers to find their way to this similarly themed movie in their further search of more “bad ass with a beard takes on all predators’ stories.”

Movieline acknowledged this bad ass/beard/predator trope by looking back at

The Edge. A few weeks after

The Grey opened Nathan Pensky’s essay noted that “this genre is certainly well-trod territory” and comparing the protagonists of both films to

Cast Away and

Into the Wild. There’s no mention in the short article of how all these films are about men. For his part, Carnahan made a joke during the promotional cycle about what an all-female version of his film would consist of: “The movie would be 15 minutes long. They’d all agree on what to do, they’d walk out and live.”

Pensky, Ge, and Carnahan all made different statements that overlap at the same points of genre and gender. The Grey is part of a film release schedule that is heavily weighted to stories about men, and a popular trope that has become a representative for stories about the male condition. The presence of women would be so improbable that it becomes humorous, detracting from the key narrative tension – Man vs. [some predatory element of nature]. It doesn’t take much Hollywood savvy to guess how few actresses will be considered to play a ‘bad ass with a beard.’

Statistics and the deluge of similar films contradict this idea that we’re losing a masculine identity from cinema. Although the space from Justin Bieber to Liam Neeson via Bradley Cooper seems like a fairly narrow distance to cover, movies focussing on (white) adult men fit in very comfortably with the current cinematic landscape. Grizzled masculinity is so secure in popular culture it’s become a reliable punchline. With the release of

The Grey’s trailer, there was a mini-meme phenomenon of lists like ‘

What Should Liam Neeson Punch Next?,’ ‘

10 Badass Adversaries Worthy of Fighting Liam Neeson’ and ‘

10 Crazy Things Liam Neeson Should Fight Onscreen.’ Simon Pegg

tweeted that: “If you do get into a fight, just say “Liam Neeson” as you throw a punch, your mittens will catch fire and your enemy’s life will fall off” and that

after exposure to the actor’s presence “I was 78% better at fighting swarthy goons.”

Being able to talk about manliness had obvious appeal when it came to selling The Grey to audiences. The ‘toughness’ of being a man was exploited as the theme of the film, then toughness of casting a ‘man’s man’ sparked a ripple of discussion. It was a discussion with a hollow centre. No matter how few sensible adversaries would be willing to take on Liam Neeson, there is no upcoming shortage in films being made about him and his kind. Bad asses with beards are not going to make cinema’s endangered species list anytime soon.

———-

Margaret Howie cheerfully lives with her love of Robert Mitchum and her feminist sensibility in South London, watching and thinking about as many movies she can see.