Written by Leigh Kolb.

As a young girl, Oksana Shachko became enraptured in her iconography classes and painted intricate portraits of religious figures. She even planned to join a convent at one point. In the documentary Je Suis FEMEN (I Am FEMEN), we see Oksana painting a Madonna and child, and we also see her painting what has become her life instead: bare breasts, masks, murals, and enormous protest signs. Oksana is one of the founding members of the Kiev, Ukraine-based protest group Femen.

While her vocations in life might appear contradictory (nun vs. topless activist), perhaps her calling has always been clear–to surround herself by women and effect change in heavily patriarchal spaces. Oksana is the “Je” (“I”) in the film–her story, as a dedicated artist and activist–dominates Swiss director Alain Margot’s film. I Am FEMEN refers not only to Oksana’s journey, but also a supportive and sympathetic point of view from behind the camera.

I Am FEMEN is a lovely, powerful film. It delves into the complexity of the movement, showing protests against coddled rapists, mistreated zoo animals, Ukrainian politicians, international sporting events, and Vladimir Putin. The audience gets a sense of the humanity of the women in Femen; Margot showcases their parents, and often shows the women in the more mundane aspects of their lives/activist work–paintings signs, cooking dumplings, working on the website.

There were a few moments that the film seemed be shot with the male gaze in mind. This is problematically, ironically reflected in a POV review:

“Veteran Swiss director Alain Margot’s vastly entertaining film I Am Femen offers an entrée into the FEMEN movement through a profile of Ms. Shachko. Looking like a cross between Simone Simon in the original Cat People and Anna Karina in Une Femme est une femme, Oksana Shachko combines an aloof beauty with a lithe physique, marking her as a natural fighter who seems to relish her endless skirmishes with the police.”

Yet I Am FEMEN seems to fully understand the contradictory nature of the male gaze in relation to Femen’s activism. In a poignant part of the film, the women are protesting the Ukraine-hosted Euro 2012 football championship (not the sport itself, they point out, but what goes in to hosting these events–displacing students to set up brothels, etc.). This comes toward the end of the film, when we’ve seen the women beaten, imprisoned, and held captive, and Oksana is concerned her apartment–which was ransacked–has been bugged. While they disrupt a game, we see footage of the cheerleaders and female entertainers dancing and performing for male audiences. There were numerous charges filed against the Femen activists after Euro 2012. The scantily clad women that were in those spaces specifically for the male gaze, however, were welcomed.

At the end of the film, behind-the-scenes activist and leader Anna and a small group appear in Kiev in 2013. She has been beaten, and they say that Russian and Ukrainian secret services have kept them from protesting. Anna joins her sister in Switzerland, and three prominent activists, including Oksana, seek asylum in France to continue their organization and activist training.

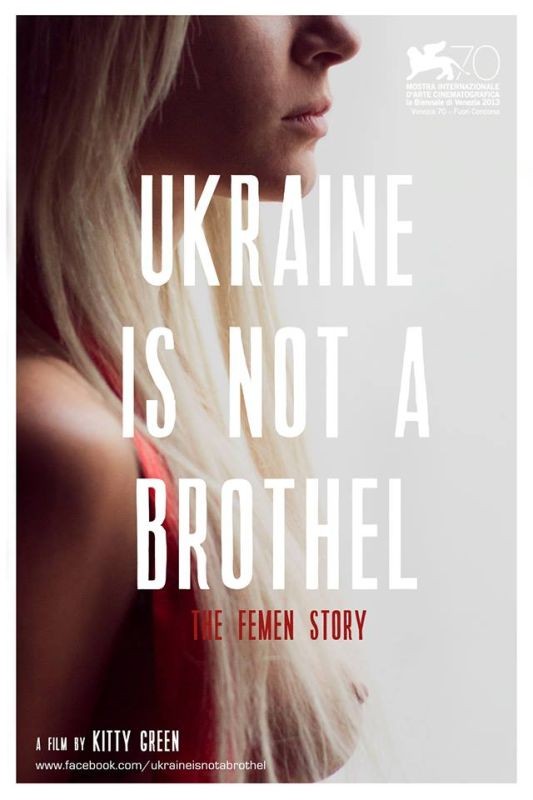

As well-shot, complex, and humanizing as I Am FEMEN is as a film, I couldn’t help but be uneasy. Because I’d seen and written about Ukraine is Not a Brothel, I wondered how I Am FEMEN would differ, since the subjects and timelines were similar. Filmmaker Kitty Green embedded herself with Femen–living with them as she shot Ukraine is Not a Brothel–and she famously “outed” Victor Svyatski as an abusive mastermind behind the scenes of Femen, whom the women eventually broke away from. He is interviewed in her film, and tells Green that the women are “weak” and that “getting girls” was part of his motivation for galvanizing the group.

In I Am FEMEN, Oksana flippantly mentions the infamous Victor, saying that he simply “supports our work,” and is a “feminist man.” While Margot told the story in front of him, if an audience member was familiar with Ukraine is Not a Brothel, the fleeting mention of Victor leaves many questions unanswered. Certainly Green’s storytelling was from a different perspective, as she lived with the women and became much more than a director. Green also focused more on Inna Shevchenko‘s journey, and Margot focuses on Oksana.

There is much to appreciate in I Am FEMEN, and much to be inspired by. Feminists in general have conflicting views of Femen, but we cannot deny the power of turning the sexual object into the angry subject. The current aim of the movement–an international reach, dubbing themselves as a “sextremist” group– is fascinating. While there are complex, complicated problems that are inherent in any activist group, attempting to subvert the male gaze–which enjoys provocative dancers yet beats and arrests topless activists–is, essentially, a forceful weapon.

Inna recently penned an op/ed for The New Statesman. She says,

“With Femen’s topless protests, we succeeded in frightening many patriarchal institutions by taking away women’s naked bodies from the shining world of advertising, and taking them back to the political arena. Here, women’s bodies are no longer serving someone else’s demands or pleasing someone else, but are instead demanding their own rights. We revealed and highlighted the double standards of a world which easily accepts the use of female naked bodies in commercials, but roars in anger when topless women bare their political demands.”

It would be most compelling to watch the two Femen documentaries as a complementary pair. Ukraine is Not a Brothel and I Am FEMEN both beautifully delve into the past, present, and possible futures for a group that seeks to push and keep pushing. In an interview with VICE, Inna discusses the Victor revelations, and confidently asserts that they’ve moved on and now they’re independent. All of this–the literal and figurative nakedness of protest, the growth of a movement, the breaking free from the external and internal patriarchal structures–teaches us that in so many ways, the world thinks it owns women’s bodies. I Am FEMEN (and Ukraine is Not a Brothel) show the worth of this organization that’s out to change the world.

I Am FEMEN is available via First Run Features and iTunes.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oaVXQVJ1Ct0″]

See also at Bitch Flicks: Ukraine is Not a Brothel: Intimate Storytelling and Complicated Feminism; Pussy Power and Control in Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer

___________________________

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature, and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.