Written by Leigh Kolb.

“Ninety nine percent of Ukrainian girls don’t even know what feminism is.”

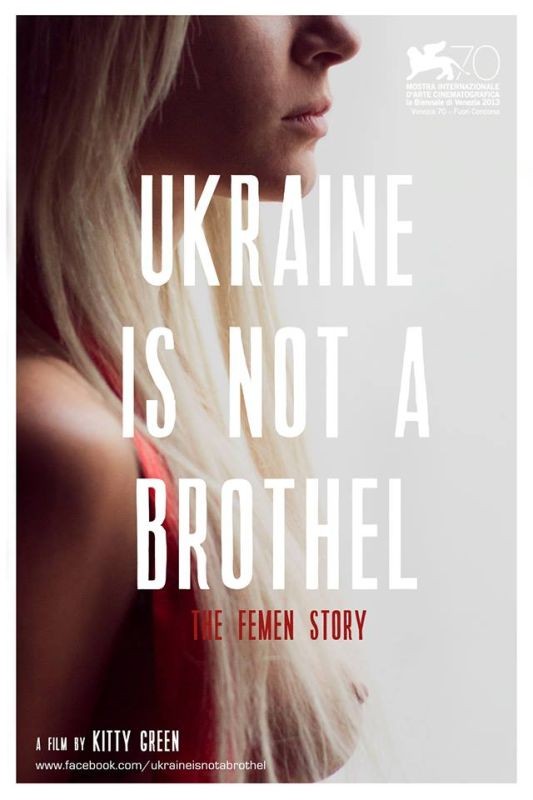

This is the sentence that opens Ukraine is Not a Brothel, which premiered in the US last weekend at the True/False Film Fest in Columbia, Mo. The film chronicles Femen and uncovers the patriarch behind the movement.

[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3_AysixuBhQ”]

The aim of Femen–the topless feminist protest organization that began in Kiev four years ago–is to shock the masses and raise awareness for that 99 percent of girls who are growing up in a society that treats women as second-class citizens and to dismantle the fact that Ukraine is seen as a hub for prostitution and sex trafficking. Director Kitty Green (who makes her feature-length documentary debut with the film) was struck by the image of a Femen protestor holding a sign over her bare breasts that said, “Ukraine is Not a Brothel,” and Green embedded herself with the group for a year, serving as their videographer while collecting footage for the documentary.

Femen says that they fight against the patriarchy and against sexism in all forms. In a Q&A after the film, Femen leader Inna Shevchenko (who was featured prominently in the film and has since moved to France) said that the goal of Femen is “fighting patriarchy and its global weight.”

Inna noted that the way Femen uses their sexuality–by running and screaming while naked, and not by posing or trying to attract the male gaze–is a core part of the protest. “We are trying to provoke,” she said, but in a different context.

Everything about Femen sounds pretty great, and their goals and messages are a shocking but valuable chapter of feminist protest.

But it’s more complex than that.

Just as the feminist movement as a whole has its issues, Femen isn’t all that it seems.

During the pre-fest Based on a True Story Conference in conjunction with the Missouri School of Journalism, Green explained to an audience that while she was living with and filming the women of Femen (she was arrested eight times and was abducted by the KGB with them, as well), she started to realize that the movement was actually run by a man who no one knew about. She said that he was abusive to the women, and she had to “shift ideas and expose him,” instead of simply filming the women. She had to secretly film him, and admitted only after she was almost ready to leave the country admit to the women that she was going to expose him.

“They needed to break away from him,” she said, and it was a difficult moment in their relationship, and in Femen. (In an announcement that got cheers from the opening-night crowd, Inna said that it’s been a year since they’ve had contact with Victor.) Green considered the women she lived with to be friends and family, and her “heart broke” when she would hear Victor yelling at them, and the next morning they were holding signs that said “This is the new feminism.”

The film does a beautiful job of dealing with the complexities and paradoxes of Femen–and really, all of feminism. Ukraine is Not a Brothel highlights the Ukrainian protestors–their lives, their struggles, and their goals–while also shining a light on feminism as a whole. Green’s intimate reporting and the incredible cinematography and editing that makes the film stand out accomplish the goal of respecting, questioning, and empowering these women activists. Green, in examining those fighting against the patriarchy, exposes and dismantles the patriarch who was running the show.

The documentary also quietly examines the difficulties that feminism has with other aspects of its modern identity. Worldwide, prominent feminists are often conventionally attractive (white) women. Third-wave feminism grapples with its relationship with sex work. Women are not widely exposed to or immersed in feminist theory. Women’s bodies are still sexualized, even when we try to use that sexuality in protest. Men still think they have the power, even in progressive movements. And oftentimes they do.

It’s all complicated. And Ukraine is Not a Brothel doesn’t offer solutions–except that the women need to be free from the patriarchal influences that are pushing and abusing them.

Green said, “Victor never thought I was capable of this. I was the young blonde girl who sounded like a child when I spoke Ukrainian. I was not taken seriously, and this gave me power.” She pointed out that women in journalism have a perceived weakness that can give them great power. “I want to keep making films about young women,” she said, hoping that this power can help her tell more stories.

If Ukraine is Not a Brothel is any indication, we can be excited and hopeful for the stories that Kitty Green has yet to discover and tell.

Inna pointed out that in all of the unrest and revolution in Ukraine right now, she gets messages from people there who tell her “You were first!” and credit Femen for being a galvanizing force in Ukrainian protest.

In the same way that Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer purposefully vacillates between humor and intense seriousness, between laughing young women and the same smiling faces screaming and being dragged away by police, Ukraine is Not a Brothel highlights the serious and violent struggle women are fighting against worldwide. These are specific, localized fights that have spread their influence around the world.

Women’s power–especially when they break free from patriarchal forces–is on display in this remarkable documentary. From Green’s intimate storytelling to the protesters’ screams, we are reminded that feminism in all its forms needs to be stripped down and critiqued while we respect and humanize the women putting up the fight and figure out ways to fight with them.

Recommended Reading: Kitty Green on KGB kidnappings and Ukrainian violence, Kitty Green Exclusive Interview, White doesn’t always mean privileged: why Femen’s Ukrainian context matters, Femen’s Topless Sextremists Invade the US

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.