|

| Mindy Kaling as Dr. Mindy Lahiri in The Mindy Project |

|

| Am I mess or a rock star intern? I can’t remember! | Meredith Grey (Ellen Pompeo) in Grey’s Anatomy |

|

|||

| Oh, I get it. It’s butterflies in the…er, ribcage. | Mamie Gummer in Emily Owens, M.D. |

The radical notion that women like good movies

|

| Mindy Kaling as Dr. Mindy Lahiri in The Mindy Project |

|

| Am I mess or a rock star intern? I can’t remember! | Meredith Grey (Ellen Pompeo) in Grey’s Anatomy |

|

|||

| Oh, I get it. It’s butterflies in the…er, ribcage. | Mamie Gummer in Emily Owens, M.D. |

|

| Mindy Kaling as Dr. Mindy Lahiri in The Mindy Project |

|

| Am I mess or a rock star intern? I can’t remember! | Meredith Grey (Ellen Pompeo) in Grey’s Anatomy |

|

|||

| Oh, I get it. It’s butterflies in the…er, ribcage. | Mamie Gummer in Emily Owens, M.D. |

|

| Edwina Shearer has a miscarriage in the first episode of season 3. |

|

| Margaret watches Carrie Duncan fly overhead. |

|

| Dr. Mason, left, and Margaret prep for their evening women’s health class (they are holding boxes of Kotex, and the nun in the background disapproves). |

|

| Margaret passes out flyers on the boardwalk. |

|

| Margaret receives a copy of Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review in the mail,. |

—

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.

|

| L-R: Tara (Maggie Siff) and Gemma (Katey Sagal) in Sons of Anarchy |

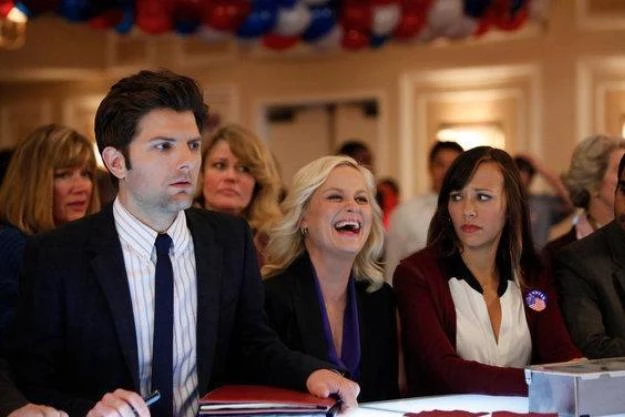

In a recent interview, Mark ‘Boone’ Junior, the actor who plays Bobby in Sons of Anarchy, stated that one of the strengths of the show is that it has, “tapped into a lot of women’s anger.”

It’s an interesting point about a show that does have some very angry women, but more so than that, it has some very violent women. Several times a season there’s a pretty physical fight between a few of the women, and not a standard hair-pulling and a few slaps kind of fight either. Gemma “nails some tart from Nevada” with a skateboard, throws around a very peppy Ashley Tisdale, Gemma and Tara beat up Nero’s assistant Carla, Tara shoots up another girls car, punches her boss, and most recently decks Gemma.

While there is often a sexual fantasy aspect associated with most ‘girl fights,’ I would posit that there is very little sexualizing of the Sons of Anarchy women during these moments, rather these fights seem to mirror the more ‘outside of society’ feeling that the male fights have.

Women’s anger is often portrayed as very catty and manipulative, rarely as physical, so in that respect, Sons of Anarchy is unique. I wonder though, are the physical encounters between these women really expressions of anger, or more a demonstration of women’s own brand of violence?

|

| Michonne (Danai Gurira) in The Walking Dead |

Warning: if you haven’t seen Seasons 1 and 2 of The Walking Dead, there are spoilers ahead.

Have you ever dated someone because of their potential rather than what she/he/ze brings to the table? Or is that just me?? Well, that’s how I feel about AMC’s The Walking Dead.

While I like the show, I keep watching the zombie apocalypse, based on the comic books, because I keep hoping and expecting it to become great – especially when it comes to the female characters and the show’s sexist portrayal of gender roles.

The conservative characters continually depict retro gender norms. The men talk about protecting the women. The women cook and clean while the men go off and hunt or protect the camp or farm. Yes, Andrea is the exception to the rule. She shoots and kills zombies and patrols the perimeter. But the women take a backseat to the men. They let the men debate, argue, decide.

I criticized Game of Thrones, a show I adore, for its misogyny. But at least it contains strong, intelligent and powerful female characters. Where the hell are they on The Walking Dead???

Which is why I’m so excited about the introduction of Michonne.

For those who haven’t read the comics (like me), Michonne, who will be played by Danai Gurira (who’s simply amazing in The Visitor and Treme) seems to be a strong, powerful, complex character. She’s clever since she uses two incapacitated walkers in order to seek out the living hide from other walkers. She appears to be a fierce and fearless survivor. But what’s even more exciting is that she’s a woman of color.

Yet I’m skeptical as the show hasn’t done a great job portraying gender so far.

Lori (Sarah Wayne Callies) does whatever Rick (Andrew Lincoln), her husband and leader of the group, says, blindly and unquestioningly standing by him. Carol (Melissa McBride), who’s keeping it together pretty well considering she’s lost her daughter and her husband, still clings to men, first her abusive husband Ed and now Daryl (Norman Reedus), who tell her what to do. The writers squandered the opportunity to explore a domestic violence survivor rather than making her a caricature. When we first meet Maggie (Lauren Cohan), she’s riding in on a horse, bashing a Walker (aka zombie) with a baseball bat. She started off so fierce, spunky and sexually assertive. It’s just unfortunate she’s unraveling, a hysterical mess who seems to cling to her BF Glenn (Steven Yeun) for protection.

The two bright spots are Andrea and Jacqui. Andrea is one of my favorite characters. A tough survivor, she’s one of the best shots and guards the camp. She did try to commit suicide, despondent after her sister died. But she’s become determined to live. She’s smart, questions the status quo, and has become more assertive, unafraid to voice her opinion. Jacqui was outspoken and seemed to possess a quiet inner strength. While I wish she’d fought harder to survive, she chooses to end her life, dying peacefully at the end of Season 1. Even though Andrea and Jacqui are the only ones, I’m glad SOMEBODY questions the ridiculous gender nonsense.

In the very first episode in Season 1, there’s a flashback depicting Rick and Shane joking about gender differences. When Rick confides that he’s having marital problems, he tells Shane that Lori accused him of “not caring about his family in front of” their son Carl. And then Rick (who I actually like a lot) says:

“The difference between men and women? I would never say something that cruel to her.”

Wow, so we’re treated to gender essentialism and a lovely tidbit that women are cruel, heartless shrews all in the first episode. This is definitely an omen of things to come.

|

| Andrea (Laurie Holden), Amy (Emma Bell), Carol (Melissa McBride) doing laundry on The Walking Dead |

In “Tell It To the Frogs,” Andrea, Amy, Carol, Jacqui wash laundry in a lake. As the women work, they see the men splashing around enjoying themselves. Jacqui, one of the only women with any common sense and a spark of strength, asks:

“I’m really beginning to question the division of labor around here. Can someone explain to me how the women ended up doing all the Hattie McDaniel work?”

YES!! Love this! How about maybe they rotate chores? Or what if (radical idea here) some of the men wanted to cook or clean? Why should the women do all the domestic tasks??

The women proceed to bond over missing their washing machines and vibrators. But then the frivolity is cut short by Carol’s abusive husband Ed who threatens the women and then slaps Carol. While the women try to defend her, Shane steps in and starts beating the shit out of him, getting out all his aggression and frustration about Lori spurning him. So even though Shane warns Ed that he better not ever lay a hand on Carol or Sophia, he’s not acting out of nobility or the belief that men shouldn’t abuse women. Not surprising as this is the same douchebag who later tries to rape Lori and then brushes it off when she confronts him about it.

Talking about women in post-apocalyptic genres, Balancing Jane asserts that while strong women exist, it’s the men who rescue them and allow them their strength:

“[The Walking Dead goes out of its] way to demonstrate that those women had to first be saved by a righteous man. In order for women to become competent and determined, a man had to first stand up and make a space for them. Until a man appeared as savior, the women were doomed to be physically overpowered and sexually exploited.”

Men continually deny women power and autonomy. Dale takes Andrea’s gun away from her (“What Lies Ahead”) like she’s a child, backed up by rapist Shane. So a grown-ass woman shouldn’t have a gun but Carl, an ELEVEN-year-old can carry one! Oh but the little woman can’t be trusted. Ugh. Dale also comments on Andrea and Maggie’s sex lives. Speaking of Carl and guns…Lori voices her opposition for her son shooting yet no one listens to her concerns. When Lori discovers she’s pregnant, Glenn scolds her for not taking her vitamins as if she doesn’t know how to care for herself. Gee thanks, Glenn, it’s not like she’s never been pregnant before.

And then of course there’s the infamous abortion/emergency contraception storyline in “Secrets.” After Lori discovers she’s pregnant, she asks Glenn to obtain medication from the pharmacy for her to terminate her pregnancy (which she admits she’s not sure if it will work). But EC is contraception, doesn’t terminate an existing pregnancy and must be taken within 72 hours of unprotected sex or failed contraception. RU-486, which does terminate an existing pregnancy, has to be procured from a doctor, not a pharmacy.

Jezebel, Slate, ACLU and many others wrote about this episode and the myths it perpetuates. Of course showrunner Glenn Mazzara brushed off the criticism saying the writers took “artistic creative license” and he “hopes people aren’t turning to the fictional world of The Walking Dead for medical advice.” Well of course people shouldn’t be. But the media influences people’s perceptions, including medicine and abortion. There’s so much misinformation swirling around abortion and contraception. And it’s this misinformation that anti-choicers use to their advantage.

If ever there was a time for a show to depict a pregnant character having an abortion…yeah, I think a zombie apocalypse would be it. But it’s strange that this abortion/contraception arc occurs in the same episode where people are debating the zombies in the barn and what constitutes life.

|

| Lori (Sarah Wayne Callies) and Rick (Andrew Lincoln) on The Walking Dead |

But it’s the reaction of those around Lori that most disturbs me. Rick screams at Lori for even thinking about terminating the pregnancy. After Maggie and Glenn return from the pharmacy (granted, they’ve just been attacked by zombies), Maggie chucks the pills at Lori saying, “Here’s your abortion pills!” So not only does Lori not turn to another woman for help (turning to Glenn instead), but Maggie yells at her for her reproductive choice. As Bitch Magazine blogger Katherine Don writes:

“When reproductive choices are navigated by a stereotyped character and manhandled by scriptwriters who don’t recognize a woman’s ability to weight options and make decisions, the woman is robbed of her individuality, humanity and dignity.”

Beyond their “individuality, humanity and dignity,” the women are also robbed of their voice. In “Judge, Jury, Executioner,” the group congregate in the farmhouse to discuss the fate of captured Randall. While Dale vehemently opposes the decision to execute him, he’s the only one who speaks up. Eventually, Andrea, who was a civil rights lawyer pre-walkers, voices her opinion that Dale’s right. Lori, who opposes the death penalty, says nothing, almost always blindly agreeing with Rick. But the worst comes when Carol says she wants no part of the decision and wants them to decide it for her. Excuse me?? You want to forget all about making the hard decisions and just sit back, letting others decide for you??

I’m so fucking tired of the writers silencing the women.

The show’s treatment of race and heteronormativity isn’t a whole lot better. Why does the one black man (what happened to Morgan and his son from Season 1??) have to be silent for most episodes and have a ridiculous name like T-Dog? Where are the LGBTQ characters? What does it say about a show where the most interesting and complex character is a racist?? Yep, sad to say but Daryl’s my favorite. Why do we have to keep hearing racist Asian jokes? Why did Jacqui, the one black woman on the show, have to kill herself??

We see female empowerment continually stripped away. Lori seems to be the worst perpetrator of gender stereotypes and reinforcing hyper-masculinity. Glenn tells Maggie that he was distracted shooting at the bar because all he could think about was her. When Maggie confesses this in “18 Miles Out,” Lori in her infinite wisdom tells her that she should let “the men do their man-work” and that it’s women’s jobs to support the men. Oh yeah, she also says, “Tell him to man up.” Gee thanks, Lori. Swell advice. So men aren’t allowed to be emotional or sentimental. Only women.

|

| (L-R): Glenn, Andrea, Shane, T-Dog, Daryl on The Walking Dead |

Later, Lori, on another anti-feminist tirade (!!!), scolds Andrea for burdening the other women by not cooking and cleaning. Lori says Andrea should leave the other work for the men, like a good little woman, don’t ya know. What. The. Fuck. When Andrea says that she contributes to the group by offering protection and keeping watch (which she does), Lori blurts out,

“You sit up on that RV working on your tan with a shotgun in your lap.”

I’m sorry, did the zombipocalypse also signal a rip in the fabric of time where The Walking Dead characters now live in fucking 1955?! So Lori, women shouldn’t be “playing” with guns or hunting for food or protecting the camp. Nope. Women are only good for domestic duties like cooking, cleaning and child-rearing. Leave the tough stuff to the men. Silly me for forgetting. Thank god Andrea told Lori and her bullshit off. Maybe Lori’s just jealous of Andrea’s skills since Lori can’t drive a car without flipping it into a ditch.

While blaming it on Lori’s “irrational behavior” due to her pregnancy and “going through a lot of stuff” (um, aren’t they all?), writer and The Walking Dead creator Robert Kirkman ultimately defends this exchange and the show’s depiction of traditional gender roles:

“Lori is really just aggravated over a lot of things and she’s lashing out. She was serious and she wants Andrea to pull her weight; certain people are stuck with certain tasks and to a certain extent people are retreating back into traditional gender roles because of how this survival-crazy world seems to work.”

So I’m really supposed to believe that when the zombie shit hits the fan, we’re all going to take a time warp? And why the fuck is it a woman, the wife of the leader of the group, who keeps spouting sexist bullshit?!

The horror genre often makes commentaries on humanity vs. brutality. Yet Kirkman clearly doesn’t care about making a social commentary on gender. And to a point that’s fine – not everything must possess some deep message. But there’s no reason the opposite couldn’t be true – an apocalypse spurring egalitarian rather than “traditional” gender roles.

All of the survivors have endured unspeakable horrors, witnessing the slaughter of their loved ones. People react differently to tragedy, some will come unhinged while others grow stronger. And wielding a gun isn’t necessarily synonymous with strength. But why must we constantly see a rearticulation of sexist gender stereotypes? Do people actually think this sexism is justified because they erroneously think we live in a post-feminist society?? When it comes to genres like horror, fantasy and scif-fi, writers can imagine any world they wish. Why imagine a sexist one? Why is everyone on the show struggling to maintain white male patriarchy??

We haven’t witnessed a fierce woman in any leadership role yet. With the arrival Michonne, I’m finally truly excited about The Walking Dead. I’m hopeful that the writers can still turn things around. With Michonne and Lauren Cohan who plays Maggie promoted to series regular, some speculate “Season 3 is shaping up to be a big one for the ladies.” But I’m still skeptical. Michonne has a lot to do to erase the stench of sexist bullshit contaminating the show.

|

| Carrie Mathison, a haunted yet brilliant CIA analyst. |

“I hate straight singing. I have to change a tune to my own way of doing it. That’s all I know.”

— Billie Holiday

“So while it is true that jazz is a demanding and competitive field for both men and women, it is also true that a woman who shows up for an audition or jam session with a tenor sax or trumpet in her gig bag is greeted with a special variety of raised eyebrows, curiosity and skepticism. Is she serious? Can she play? Time-worn questions about women and jazz buzz through the room before she blows a note.”

|

| Carrie’s personal and professional lives weave together–the professional trumps the personal, but her private battles threaten her career. |

|

| Saul serves as a mentor to Carrie. (Patinkin has been outspoken about issues of television and feminism.) |

“It’s ill-becoming for an old broad to sing about how bad she wants it. But occasionally we do.”

— Lena Horne

“Jazz is not just music, it’s a way of life, it’s a way of being, a way of thinking. . . . the new inventive phrases we make up to describe things — all that to me is jazz just as much as the music we play.”— Nina Simone

“Monk was hospitalised at various points in his career due to an unspecified mental illness and there has been some debate about whether he could have had a schizophrenic or bipolar disorder. (In fact, jazz and schizophrenia have long been linked. It is argued that New Orleans cornetist Buddy Bolden, the ‘inventor of jazz’, improvised the music he played as his schizophrenia did not allow him to read music, evolving ragtime into a more free form of music in the process.) It is an association that positions Carrie, who takes anti-psychotics, as a ‘crazy genius’ like Monk.”

|

| Nick Brody and Carrie develop a complicated relationship, although her theories of his terrorist involvement were correct. |

“When I was a girl, my friends and I used to play chicken with the train on the tracks near our house and no one could ever beat me, not even the boys.”

“One day a whole damn song fell into place in my head.”— Billie Holiday

|

| Carrie chooses to undergo ECT, as she convinces herself in Season 1 that her suspicions about Brody are delusions. |

“Carrie does not suffer from the common female need-to-please trait and, in fact, insists she is usually right. She is impulsive in a job that rewards patience and lies to the few people who can tolerate her…You root for her because those very despicable qualities also make her extraordinarily good at her mission. Danes breathes life and realism into a character who, for once, goes against the clichés of what a female CIA officer is supposed to do and look like.”

|

| Carrie is back in action in Season 2, and Saul is listening. |

|

| The cast of Downton Abbey |

|

| Lady Rosamund and her beau, Lord Hepworth |

|

| Lord Grantham and the Dowager Countess discuss Lady Rosamund’s finances |

———-

[ii] Sharon Marcus’s excellent 2007 Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England is a wonderful, immensely readable but rigorously scholarly exploration of the full spectrum of female friendships, from the platonic to the intensely erotic. However, Marcus’s data is primarily drawn from sources written by historical women of the middle class, and some of their experiences (going to school, e.g.) would not have applied to any of the Crawley daughters. Lillian Faderman deals with the spectrum of friendships in the United States in roughly the same time in 2001’s To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America, which includes chapters on upper-class women.

———-

|

| Louis C.K.’s Louie |

|

| Louie eats dinner with his two on-screen daughters. |

|

| Parker Posey plays one of Louie’s love interests in season 3. |

|

| C.K. used his own experiences and inspiration from his daughter to create “Duckling” in season 2. |

**I’m assuming that the people who are reading this article, have caught up pretty far into both of these shows, so some spoilers are present.

Breaking Bad

High school chemist turned god-like meth creator. Walter White’s (Bryan Cranston) journey from quiet grading to bloody drug kingpin is engrossing and incredibly well done. May I also say, that “Yo, bitch” and “Yo, Mr. White” have officially become standard in my vocabulary and I root daily for Jesse (Aaron Paul) to be a winner.

Sons of Anarchy

Sons of Anarchy follows the misadventures of the original chapter of a motorcycle club in Central California, the Sons of Anarchy. Sons of Anarchy are an obvious reference to Hells Angel’s (which has been classified as a criminal organization by the US Department of Justice) and likewise the Sons are arms dealers who sell IRA guns to drug lords. The arrangement is more complicated than just some gun runners though, the Sons of Anarchy are a respected organization in their small town of Charming; they own the police and in exchange for their cooperation and silence, protect Charming from drugs and gang violence. The show is further complicated by it’s Hamlet-esque plot line for the young protagonist, Jax (Charles Hunnam), who begins to doubt the Sons actions and wants to move away from arms dealing (although he manages his fair share of brawls, murders and the occasional knife fight).

Being from Northern California, the backdrops and town names are familiar to me, as is the sight of a large group of bikers cruising down a California highway. Even the sights of New Mexico in Breaking Bad seem homelike, with that crisp desert and blue sky. I find it interesting that both shows take place in the West—the home of cowboy justice; the Wild West still holds some draw to us and remains the place where fortunes can be made and men become men.

Anyone would say that Walter White from Breaking Bad is a raging egomaniac trying to become an alpha male (“I’m the one who knocks”) and that the Sons of Anarchy are territorial egomaniacs who seek to maintain their alpha male status. Both groups of men, while able to beat-up various other bad guys with impunity and whose criminal activities just serve to fuel their need to do so, constantly reiterate that their violent activities are necessary for the protection of their families.

Each group uses family and honor as a justification for their own aggressive desires, espousing an almost medieval chivalric code of honor, one where “the family” is paramount, but pride, strength, and respect are the true priorities. This portrayal of such harsh masculinity is one where the only way to reclaim one’s sense of honor and control, is through violence.

The men in each of these shows maintain this violence with constant rationalizations about how they and their protection is needed by the ones they love. Jax puts a man into the hospital with a horrific beating when he discovers that he sold drugs to his ex-wife. Walt kills Tuco and his cousin, up close and personal, because he believes that they might hurt his family. Vigilantism and backdoor deals are treated as the only way to keep their families safe, despite the obvious truth that it’s that very behavior which has brought them to that point.

There is an obvious hierarchy displayed by each group: either you’re smart enough to live outside of the law, or you’re a sheep. These men who embrace a counterculture lifestyle, place themselves, their intellect, even their consciousness at a higher level than those around them, as if they are entitled to live the way that they do because they remain free from it’s taint. Their honor remains intact because their motivation (family, freedom, love) is pure (or so they believe), a fact that places them above common gangsters.

However, the reasons for the justification have to remain pure as well, meaning that gender roles, must be strictly upheld, otherwise, what are they fighting for? Walt resents Skyler’s need to work, only being supportive when she is actually laundering money for him. His sexual dominance towards her increases as well, needing to feel in control of her behavior.

Sons of Anarchy especially uses gender roles with women pushed into two groups, prostitutes to be played with and passed around the men, and the legitimate “Old Ladies” who are the matriarchs. While these women (in particular Gemma and Tara) are afforded great respect, they are still expected to oversee the comfort and maintenance of the families, while also turning a blind eye to any wayward straying of their men.

The women in Sons of Anarchy are complicated and full of their own issues and ideas and even their own unethical and immoral rationalizations. For me, one of the most interesting arcs of the show has been to see the change in Tara, an intelligent doctor who becomes dangerous in her own right when she attacks a hospital administrator who has suspended her. Gemma is likewise fierce, being gun toting, punch throwing, and threatening all on her own.

Skyler and Marie are complicated protagonists as well, and not fully innocent either. Skyler starts to launder money, has Saul on her speed dial, and arranges for Ted Beneke’s intimidation (even finishing the job herself).

Yet, even as these women are somewhat outside of the norm because of their lifestyles, I think that both shows do a great job at featuring women who are varied and interesting, many of who have reclaimed their sexual nature in spite of the way that they are manipulated and treated by the men in their lives (Bitch Flicks contributor Leigh has a great article discussing this trend).

However, those considerations are secondary to this article. Rather, the focus is this question, what does it mean to be an “alpha” among humans? Is that drive still as present as these shows say it is? And, can you be an “alpha” without being a criminal?

Rachel Redfern has an MA in English literature, where she conducted research on modern American literature and film and it’s intersection, however she spends most of her time watching HBO shows, traveling, and blogging and reading about feminism.

|

| Yaaaaay! |

|

| Tina’s my favorite. No, Gene is. No, it’s Louise. Oh, don’t make me choose! |

|

| ASDFSDALF;HDSLGJKHSJDK |

|

| Michelle Trachtenberg as Dawn Summers |

|

| Dawn and Tara, fellow outsiders from the Scooby gang, pass time with a thumb war. |

|

| Dawn as annoying little sister. |

|

| Dawn in damsel-in-distress mode. |

|

| Dawn writes in her diary. |

|

| “It doesn’t matter where you came from, or how you got here, you are my sister.” |

|

| Dawn’s tantrum in Season 6’s “Older and Faraway” |

|

| Buffy and Dawn hug in “Grave” |

|

| Dawn with Buffy during her metaphorical rebirth in “Grave.” |

|

| Dawn lurks in the background as Buffy gives a speech to potential slayers. |

|

| Xander has a heart-to-heart with Dawn |

|

| Dawn accepts her humanity and finds her maturity. |

|

| The cast of Buffy the Vampire Slayer |

At the end of my first 45 minutes with Sunnydale’s finest, I remember feeling absolute delight. On the promise that they be returned in perfect condition, I borrowed one series after another of my friend’s treasured DVD boxsets, handed over with warnings and reverence, and received with the desperation of an addict. Needless to say I watched nothing but Buffy until reaching the final episode of Season 7 (it didn’t take long). I love this show. I believe it to be one of the most important television shows that has ever been conceived. Yes, there is the Riley blip, and Tara is no natural Scooby, despite her witchy credentials. But out of 144 episodes – that’s almost 7 days of watching Buffy continuously for 16 hours a day* (you’ve got to sleep right) – these niggles are small. It is a work of genius, and I will argue violently against any dissenters.

And yet … I am not particularly a fan of Buffy herself. I’m always on her side when she’s facing the bad guys, whether it’s The Master, Mayor Wilkins, Glory or the downright terrifying Caleb. But when it’s Willow, Faith or Anya that Buffy’s fighting, I can’t help feeling she sort of has it coming.

The entire show champions under-dogs: the nerdy, the quirky, and the excluded. People who aren’t classically beautiful; the unpopular ones that you’re embarrassed to hang out with; the screw-ups and lost souls. And with her perfect hair, kick-ass fighting skills, cool outfits, and dangerously sexy boyfriends, Buffy just doesn’t evoke the empathy of some of her fellow Scoobies. Sure, she has some romantic tangles along the way (excuse the enormous understatement), and definitely messes up occasionally: trying to kill her friends and sister; running away to leave Sunnydale to certain destruction; dying – all notable examples. But when it comes to saving the world, she delivers. She’s awesome at her job. And boy does she know it.

|

| Faith, Buffy’s “rival” slayer |

So when Faith arrives and ends up rocking Buffy’s world, there’s a wonderful satisfaction in watching the pair battle it out. Unpredictable, sexy and wild, Faith personifies the dark side of Buffy: what she could have been if she wasn’t so annoyingly right all the time. But more than that, Faith’s psychological issues make her empathetic: her psychotic behaviour is not only understandable, but almost forgivable. From an unstable and implied abandoned background, Faith openly wishes for the wholesome simplicity Buffy’s life retains despite her Slayer responsibilities. She has a touchingly childlike desperation for the conventional stability that the Scoobies, Giles, Angel and Joyce provide for Buffy. The Mayor’s fatherly affection for Faith appears the only stable relationship she has ever come across, where she is treated like the innocent little girl she seems to have never been allowed to be. It is no wonder that she would do anything for him: wouldn’t most of us do anything for our family after all?

Faith is an emotional Slayer, and it is not a straightforward job for her – she is driven by instinct, pain and desperation, and pushes Buffy further than any of her other adversaries up until that point. When Buffy stabs her at the end of their final confrontation in Season 3, she commits the very action that she condemned Faith for. That Faith survives is the only thing which saves Buffy from a hypocrisy that will stalk her in further conflicts.

But when it comes to Buffy’s hypocrisy and double-standards, no situation makes them clearer than the moment she all too easily decides she has to kill Anya in Season 7’s “Selfless.” Being a bad-ass Vengeance Demon notorious across numerous hell dimensions, Anya is nowhere near as harmless as the bunnies she has an illogical phobia of. Her confrontation with Buffy is vicious, and bloody, and is without a doubt one fight we’re really not rooting for Buffy to win.

|

| Vengeance Demon Anya |

Anya’s devastation after being jilted at the altar by Xander guts her emotionally. When she renews her status as a Vengeance Demon, it’s driven by desolation and grief. Like a lost soul she is doomed to meander through Sunnydale with no sense of purpose after her excruciating break-up with the love of her life, and finally resorts to her work as her only source of pride and fulfilment. The fact that that happens to include administering gory punishment to insensitive frat boys serves first to show the ravages her soul has endured – but subsequently her compassion when she bargains for them to be brought back to life.

Similarly Xander is all too aware of how painful the repercussions of his commitment-phobia are, and pleads with Buffy not to kill his one true love. When Buffy tells him she faced this problem when she stabbed Angel way back in Season 2, I can’t be the only one that felt she had milked that drama one time too many! And here’s why … To compare that relationship with Xander and Anya’s is immature at best, and delusional at worst. Xander and Anya move in together. They get engaged. They profess their love for one another openly. They plan to have children. They can spend whole days together without apocalypse as an excuse. And most importantly of all, they have lots and lots of sex.

Their physical connection, their delight in carnal intimacy, their inappropriate lustful outbursts are demonstrations that Anya and Xander are a grown-up couple. To compare the adult subtleties of the way they relate to one another with the doomed fairytale of Buffy’s teenage love affair shows a complete lack of empathy and understanding on Buffy’s part. She has no idea what it is like to experience love of the kind Anya and Xander share: where it isn’t “end-of-the-world” urgency all the time! Her response to Xander’s pleas with, “I am the law,” before leaving to kill fellow Scooby, Anya, out of some presumed sense of morality simply reeks of arrogance.

Thankfully, Anya survives Buffy’s assault, and in doing so she gives her a glimmer of insight into the lengths love, and not responsibility, will drive a person to. Amazing that after the show’s most exhilarating confrontation of all, she’d need a reminder of that, but it’s a lesson Buffy clearly doesn’t learn easily.

Buffy vs Willow: replacing “and” with “vs” surely never had a more devastatingly exciting depiction onscreen!

As one of the most popular characters, and with an incredibly complex character arc, Willow is arguably the reason why I love this show so much! Endlessly patient and studious throughout Seasons 1 and 2, over time Willow transforms into the embodiment of the “Woman Scorned” becoming a murderous and merciless master of dark magic in Season 6. In this gothic incarnation of unrestrained power Willow expresses all the suppressed frustrations she’s endured as Buffy’s “sideman.” She flaunts her strength, exhibits her magical prowess and becomes the personification of her enraged emotions. There’s a cathartic thrill at seeing someone previously so meek rebel. Countless times over numerous episodes we watch Willow put her own dramas to one side to prioritise Buffy’s needs, but with the death of Willow’s soul-mate she finally lets her instincts take over. Right or wrong lose significance and at last, Willow’s emotional needs are given priority – that she almost destroys the world in the process doesn’t say much for Buffy’s ability to empathise with her dearest friends!

|

| Dark Willow |

So whilst Buffy can defeat demons and save the world over and over, her emotional detachment and self-righteous sense of martyrdom (have some humility woman!) make these fights she doesn’t actually win, absolutely crucial to the Series’ greatness. Ultimately that’s why I find it hard not to let out a little yelp of glee when Dark Willow declares, “You really need to have every square inch of your ass kicked.” Faith, Willow and Anya teach Buffy to lose the ego and remember what she’s really fighting for, and that’s feminism in action right there.

*I am no mathematician, and it is testament to my love for Buffy that I actually worked this out.

———-